More Than Credit: Can microfinance also deliver affordable health care?

In Bangladesh, 65 percent of health expenditures are out-of-pocket payments. This lack of funded health care puts considerable pressure on the millions of people with debt from microloans. For many, a health emergency means much more than paying loan installments late; it can mean liquidating business assets that put an end to income-generating activity indefinitely, or going to informal money-lenders who charge exorbitant interest rates.

To date, most attempts at marrying financial inclusion with access to health care have centred on micro-health insurance. This makes sense – the poor are the most vulnerable to both health problems and financial shocks, and should have greater demand for health coverage than any other market. In reality, the microfinance sector has had difficulty convincing poor people to pay insurance premiums for a service from which they may never materially benefit. Almost all microinsurance initiatives to date have been heavily subsidised, making them unattractive products MFI investments.

An alternative model that has shown encouraging signs of success, in both Bangladesh and abroad, is health loans. One third of late loan installments from BRAC’s microfinance clients (mostly poor rural women) are caused by health emergencies in the family. These are usually events such as child delivery or minor surgeries.

In October 2013 BRAC launched its very own health loan pilot – the “medical treatment loan” – designed to absorb sudden health shocks by providing clients with additional finance met with access to quality, affordable health care. For this, BRAC’s Microfinance Programme partnered with BRAC’s Health Programme, which provides extensive health services across the country.

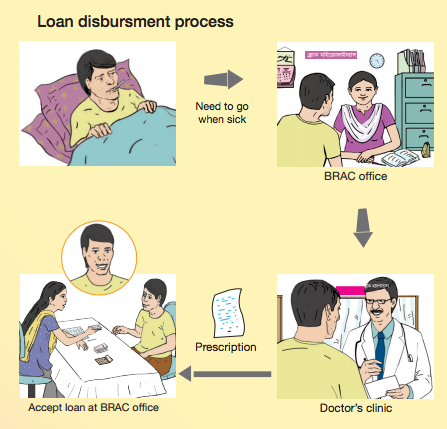

In the event of an illness within the family, existing BRAC microfinance clients can qualify for medical treatment loans. They collect a slip from a BRAC office, with which they visit a local doctor at a discounted rate. Following consult, the doctor issues a prescription along with an estimate of the treatment costs. The client returns to BRAC and a loan is disbursed based on the prescribed amount and our judgment on a client’s ability for repayment.

An early example involved a client who was prepared to sell her cows to cover the costs of her gall bladder surgery. The medical treatment loan prevented her from liquidating her assets and she took out a 20,000 Bangladeshi taka (£165, or $260 U.S.) loan instead, for which she pays regular instalments.

An early example involved a client who was prepared to sell her cows to cover the costs of her gall bladder surgery. The medical treatment loan prevented her from liquidating her assets and she took out a 20,000 Bangladeshi taka (£165, or $260 U.S.) loan instead, for which she pays regular instalments.

(Training material developed by BRAC to explain medical treatment loans to clients, left.)

In most cases, medical treatment loans are made available within three business days. Most loans range from £25-100, and repayment periods vary from six to 24 months, depending on individual cases. The first loan installment is paid within two to four weeks of initial disbursement. To keep things simple, the same policies and rates apply, and loans are repaid via the same community borrower groups to which clients already belong.

Medical treatment loans are available across the districts of Rangpur, Bogra and Jessore, Bangladesh, providing access to approximately 200,000 households. Within the first year, BRAC disbursed more than 1,200 loans – a total of £77,833 – indicating a real need for formal health finance.

Field officers, all too familiar with the devastating effects that health problems can have on families, were also receptive to the provision of medical treatment loans.

Having their full support was key. As BRAC did not hire additional field staff, piloting the project involved taking on additional responsibilities. Furthermore, having already worked in the community, field officers are best placed to build understanding of local health needs and earn the trust of clients.

But trust must come both ways. In the early stages of the pilot, BRAC learnt that some clients who had received their loans would use part of the lump sum for non-medical related expenses. To mitigate risk, for both clients and us, BRAC introduced a two-step disbursement process. BRAC releases part of the loan to cover initial treatment costs – e.g. a blood test. Once confirmation of a client’s treatment is received, BRAC disburses the remaining loan amount to cover further costs – e.g. for surgery. (In rare emergency cases, larger loans can be disbursed in one.)

The loan realisation rate for the pilot has been an encouraging 99.5 percent. However, expanding the reach of the loans won’t be easy. Hospital accreditation systems are weak in Bangladesh and finding trusted health providers in each area is difficult. To avoid fraud, their services must be monitored closely – putting pressure on BRAC’s health team.

If scaled, the medical treatment loan has real potential to provide access to quality health care for millions of poor families in Bangladesh, in a way that is affordable for both MFIs and clients.

With that said, the medical treatment loan is not a solution to the lack of health care for the poor, but an improvement. Unlike in most developed countries, people with low incomes are still expected to bear the brunt of their health care costs.

As clients start to think more about health care, medical treatment loans could act as a stepping-stone to sustainable solutions that provide comprehensive coverage.

Isabel Whisson is communications and knowledge management officer and Moonmoon Shehrin is a management professional for the BRAC Microfinance Programme.

- Categories

- Education, Health Care