If (When) At First You Don’t Succeed …: Multinationals are refining marketing strategies to reach the BoP

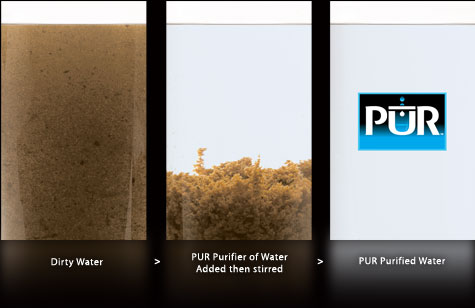

In 2001, Proctor & Gamble Co. thought it hit the jackpot when it created a water purification system called PUR. Not only was PUR easy to use, but it cost only 10 cents to turn 10 liters of murky, contaminated water into drinking water.

PUR addressed one of the world’s greatest health threats: contaminated water, which claims the lives of about 1.5 million children a year. Proctor & Gamble had done its research and conducted a well-planned marketing campaign, including years spent engaging local communities in the development of its product. Research indicated that PUR would sell.

To the company’s surprise, PUR famously tanked, failing to yield a competitive return. Eventually the business model disintegrated into a purely philanthropic effort, providing a much-needed public health service but dashing the company’s dreams of tapping the low-income consumer pool, which sits at about 4 billion people.

Proctor & Gamble is not the only company to lust after this potential consumer goldmine. Others have tried. Some successfully, many not.

Part of the difficulty is that people at the base of the pyramid were not a target consumer audience until recent years. Many companies are only now writing the script for what works and what doesn’t. The business code is entirely different than it is when dealing with a more affluent consumer base.

Erik Simanis, an expert in sustainable global enterprise at Cornell University, used Proctor & Gamble as an example in a 2009 Wall Street Journal article highlighting some of the challenges of creating a product for a demographic that by definition is not consumer-minded. His conclusions are still as relevant today.

Erik Simanis, an expert in sustainable global enterprise at Cornell University, used Proctor & Gamble as an example in a 2009 Wall Street Journal article highlighting some of the challenges of creating a product for a demographic that by definition is not consumer-minded. His conclusions are still as relevant today.

(An ad for P&G’s ill-fated PUR water filter.)

“Consider some of the changes a villager would need to make to make PUR part of her daily routine,” Simanis writes. “She might have to reassess age-old folk knowledge and home remedies and learn about bacteria. Likewise, she might have to jettison long-held beliefs about what clean water looks and tastes like.”

However, companies that successfully appealed to low-income consumers found a brisk market.

-

Puriet, an in-home water purification system designed for low-income consumers, has sold more than 45 million units worldwide. The system operates without electricity or water pressure and is simple to use. But it costs $25 – a month’s income for an impoverished person living in India. To offset the price, manufacturer Hindustan Unilever Limited, the world’s largest consumer goods company, created an installment plan that allowed families to pay off the purchase over the course of six months.

-

KickStart, an African aid organization, aims to “develop, launch and promote simple money-making tools that poor entrepreneurs could use to create their own profitable businesses.” It created multiple products at low-cost to sell to rural farmers, including an irrigation pump, oil-seed press, block-making press and a hay baler. Since hitting the market, KickStart has focused on the irrigation pump after finding it accounted for 98 percent of its revenue.

But the more common, unsung tale is that of the companies that seemed to have a needed product, but still found that it flopped.

-

Dupont Co. and its subsidiary Solae faced difficulty selling its soy product to families living in India, despite projected success early on. The soy packets contained about 50 percent of a woman’s average daily protein needs, and Solae’s business model was built around partnering with women who in turn held cooking seminars with members of their community, incorporating the product into traditional dishes. Simanis noted that Solae failed because the percentage of people who would need to buy the product to make it profitable was unreasonably high. “Any company that starts off needing a 30 percent or higher penetration rate is built on a shaky foundation,” he said.

-

Nokia 105 was introduced in developing countries by Microsoft in 2013. The tiny mobile phone sold for as low as $25. It featured a dust- and splash-proof keyboard, flashlight, alarm clock and FM radio, as well as a battery charge that supported 12 hours of talk time and could last about 35 days on standby. Catered to its customers needs, the phone was unable to foster financial gains for the company, despite selling millions of phones.

The reasons multinationals are struggling to breach the poorest consumer pool are abundant. It is difficult for companies to break even unless their products are sold in extremely high volume. Additionally, it may take years for the product to be understood and developed to the point that it convinces the poorest people to indulge.

The solutions? According to a 2012 article in The Economic Times, a company can either forget about making a profit and turn it into a charitable pursuit, as Proctor & Gamble did. Or it could aim for the rung right above the bottom of the pyramid, where people have similar needs but slightly more money:

“BoP is a great strategy, but it’s only for those who are willing to ride the long haul and wait patiently for the much-elusive profits to show. For those who don’t have the confidence – and the deep pockets – to keep pegging away at the bottom, the options are two-fold.”

For those willing to fight the uphill battle to benefit people with the greatest need – while also seeking a potential fortune – there are a few guiding principles that most success stories have in common.

-

Working closely with local communities in the development and implementation phases of a product release, to ensure the product is feasible and culturally appropriate

-

Convincing people of the benefits of changing their lifestyle to include the product at hand, even if it appears daunting

-

Educating people about how to use a product (possibly one of the pitfalls of the PUR campaign)

-

Putting out many products, then being adaptable based on consumer feedback (why KickStart found success)

As Proctor & Gamble, Microsoft and many others have discovered as they navigated the complex values and needs of low-income consumers, there is no recipe for success. Yet. Until there is one, it’s back to the drawing board.

Sophie Wilson is an intern with Global Envision, a blog managed by Mercy Corps where this article was originally published. It’s been republished with permission.

- Categories

- Uncategorized