Where the ‘New Formal’ is the New Normal: Lessons on Innovation from India’s Artisan Economy

In India alone, over 200 million livelihoods are directly or indirectly linked to the artisan economy. This sector is a primarily rural, informal and creativity-led landscape. It also has a very high concentration of micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) that drive labour-intensive and skill-intensive employment. Unlike modern manufacturing approaches that are concentrated in a few geographies, the artisan economy has an all-pervasive reach, thereby making it India’s second largest source of employment and livelihood after agriculture. And unlike most formal enterprises, the business models of craft-based enterprises in India are customised by necessity to meet informal, creative communities where they are — in dispersed, often inaccessible rural areas.

This is important because more than 50% of artisans in India are women and marginalised groups, whose mobility is greatly restricted due to cultural and social norms. From a gender-lens perspective, this makes the artisan economy crucial for inclusion, addressing a vital challenge for a young economy like India — the declining labour participation of rural women.

Thanks in part to these characteristics, the artisan economy already advances 12 out of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This is possible because formal craft-led businesses/MSMEs in India have a unique growth trajectory. They become key nodes for greater financial and social inclusion by employing informal rural communities and deploying necessary social protections (i.e., access to bank accounts, government schemes, government-issued ID proofs, etc.), thereby formalising them. They also serve as models that demonstrate how environmentally sustainable and socially inclusive businesses can drive profitability.

With 90 million new non-farm jobs needed in India by 2030, the creative/social enterprises in the country’s artisan sector should be lauded as the next frontier of impact. But they are not. Instead, these businesses continue to face systemic bias across the cultural, social, policy and investment spectrums. Below, we’ll discuss the reasons for this lack of support, and explore a solution that combines the advantages of informality with the benefits of formality to empower these enterprises and the communities they serve.

THE ‘NEW FORMAL’ — BRIDGING THE GAP BETWEEN THE FORMAL AND THE INFORMAL

Much of the rhetoric around impact, innovation and inclusion does not account for informality. Traditionally marginalised communities often operate within the grey spaces of the informal economy, which accounts for over 60% of the global workforce. In India, this number is much higher. Informal business activity is no doubt messy, but what it cannot currently promise in terms of economies of scale and corporate-style efficiencies, it more than makes up for in its significant contribution to India’s GDP.

Among emerging economies like India, the conversation around the informal economy becomes altogether more significant when we throw creativity, culture and heritage into the mix. Many of these informal enterprises operate within traditional creative cultures – i.e., the cultural economy. But sadly, policy, investments and innovation ecosystems neglect both the informal and cultural economies, limiting these businesses’ ability to scale sustainably.

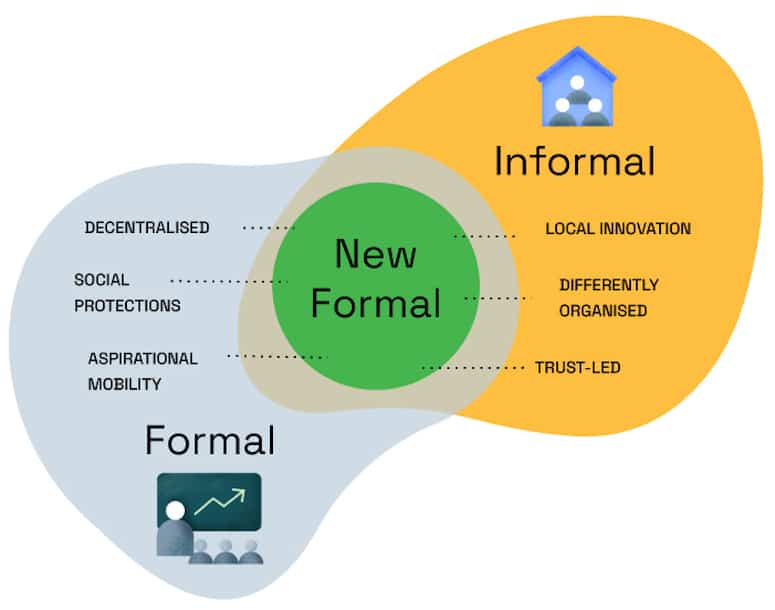

In response to these challenges, formal social/creative enterprises can adapt to and accommodate informality as part of their business model in an approach that we term the “New Formal.”

The New Formal, as seen in India’s artisan economy, is an emergent hybrid approach that combines the benefits and best practices of the informal space (e.g., cultural networks, labour relationships, and behaviours rooted in social, familial, ethnic and caste dynamics) and the formal space (e.g., social protections, data, and economic and social mobility). We see it as a dynamic continuum anchored by entrepreneurial creativity and livelihood generation. It combines the flexibility and complexity of cultural interactions from the informal economy with metrics from the formal economy, such as literacy, compliance and finance. This formal-informal interplay has the potential to facilitate a more equitable and inclusive dialogue between diverse stakeholders across the policy and investment landscapes.

The New Formal (Krishnamoorthy & Kapur, 2021)

The characteristics of the New Formal, as observed in India’s artisan economy, include:

- Differently organised: Modes of production and engagement are rooted in familial and sociocultural relations and formalities.

- Decentralised: Decision-making is redistributed across geographies and communities, and within organisations.

- Trust-Led: Various approaches, like co-creation and co-ownership, aim to lower trust deficits across the public-private-community landscape.

- Localised Innovation: Indigenous models (structural, material and environmental) and local initiatives are used to address global and local challenges.

- Social Protections: The participation gap in informal cultures is reduced via labour rights, financial access, digital inclusion, etc.

- Aspirational Mobility: The potential of informal communities as active consumers and producers in future economies is catalysed.

Formal craft-based enterprises like Industree, rangSutra, Jaipur Rugs, Xuta, Kadam and others are adopting these New Formal approaches, and what makes them exciting is how informality and inclusion are the bedrock of their business models. These enterprises have adapted to local needs and contexts, and they also navigate labour relationships differently — i.e., by recognising that an artisan could be a wage-worker and a home-worker, a self-employed entrepreneur, or a part-time job-seeker.

These measures have also had an impact on these companies’ growth and financial sustainability. Undoubtedly, there is a deep-rooted perception among the global innovation community that businesses operating within the cultural economy and working with informal workers can never scale. However, we have seen that when craft-led enterprises achieve scale, more often than not, it happens through informal and decentralised collectivisation rooted in the New Formal.

For instance, rangSutra is an artisan-owned social enterprise that supplies handmade products to bigger companies like IKEA. It employs more than 3,000 artisans, and over 2,000 of them are direct shareholders, 70% of whom are rural women who live in remote villages. Craft-based work often provides them with their first experience with financial independence and social protections, which usually begins with opening a bank account.

Similarly, Jaipur Rugs (also documented by C.K. Prahalad) directly works with 40,000 artisans — 85% of whom are women and 7,000 of whom belong to marginalised tribes. Their unique “factory-less” model offers a tried and tested pathway to adopt non-industrial modes of formalisation and scaling, enabling weavers to work from home — with access to their children and families — making them happier and more productive. This philosophy, combined with a supply chain that brings high-quality wool and silk rugs to 60 countries, provides Jaipur Rugs with annual revenue of $25 million.

RETHINKING BUSINESS APPROACHES FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

We can no longer ignore the importance and role of the “New Formal” and craft-led enterprises/MSMEs in driving long-term employment creation and economic growth in countries like India. But for these businesses to achieve their potential, they’ll need support. Here is why and how impact-focused actors can step up:

- Bridging Information Gaps: Asymmetric data inhibits artisan and MSME access to global-local networks, marketplaces, service providers and investors, thus impacting their growth and scalability. This also impairs engagement by institutional actors such as banks, government bodies, etc. in critical areas such as infrastructure, credit, education and market access. As a result, craft-based work — which is pro-people and pro-nature — remains underrepresented as a priority focus area in policy and investment.

- Making Policy Responsive: The absence of reliable figures on how many artisans or craft-based enterprises operate in this sector only fuels state and institutional apathy — a missed opportunity on all counts. Policy cannot be created without context-specific mapping — both qualitative and quantitative.

- Reimagining Access to Capital: While India is fast becoming a focal point for impact investing, much like in other parts of the world, the pool of investors remains limited to sectors such as education and financial inclusion. Catalytic capital can step in to unlock the potential of craft-based MSMEs and level the playing field for these entrepreneurs. This means employing mixed strategies — grants, concessional debt and equity — to address working capital requirements. But this can only happen if investment meets the enterprises in India’s artisan sector where they are. The right kind of capital access can drive aspirational mobility at the bottom of the pyramid, enabling informal, rural communities to become the empowered producers and consumers of the future.

- Redefining Scale for the Artisan Sector: Social and creative enterprises in the artisan sector are differently motivated, prioritising creativity, purpose and impact over market-rate returns. Scale is achieved via decentralised collectivisation anchored in the New Formal. The decentralised approach significantly lowers entry barriers for differently skilled communities, especially women. The women associated with Xuta’s threadbank initiative, for example, have started reinvesting the money earned at the thread bank into other small-scale endeavours like animal husbandry, to continue the virtuous cycle. Innovation ecosystems thrive when they recognise that what is right for the artisan communities influences the right size for the enterprise.

- Supporting the Ecosystem for Innovation: It is evident that context-specific entrepreneurial action in the handmade sector can catalyse the inclusion of informal and traditionally marginalised creative communities, in order to achieve the SDGs by 2030. In the handmade sector, this entrepreneurial action can contribute to building the collaborative and equitable supply chains of the future. To that end, IKEA’s partnerships with enterprises like RangSutra and Industree are now informing the company’s global approach. Such partnerships create two-way learning, and enable many more informal communities to be integrated into formal ecosystems. However, we in the development sector need to support and incentivise these bottom-up, rights-based solutions rooted in co-ownership, co-creation and shared values.

CULTURE AS THE DRIVING FORCE IN THE NEW ECONOMY

Entrepreneurial action in the cultural economy, as seen in India’s artisan sector, clearly plays a vital role in bridging the gap between the formal and the informal. In any cultural economy, “culture” — any individual or group’s unique social behaviours and norms — carries tangible value. Cultural practices are the core drivers of many goods and services that also influence non-cultural industries. For example, a tribal terracotta tile maker will make a roof for a neighbouring farmer who gives him grain, in the age-old practice of bartering that is still prevalent among many rural communities across India. Cultural factors also affect the interactions between businesses and their customers, competitors and supporters. For instance, in Global South countries like India, business relationships are not merely transactional but are trust-based. The influence of culture drives the intertwined nature of formal-informal economic activities, which means that enterprises operating in this sector need to take a more holistic approach to value creation.

In the aftermath of COVID-19, in order to rebuild broken economies and reverse deep-rooted mindsets, we need to move away from Eurocentric notions of formality, scale and success. These only reinforce impossible expectations of growth — not self-sustainability — allowing little room for nuanced and ground-up explorations of regenerative business models. A new approach to business is needed, and India’s artisan economy can point the way toward a more effective roadmap.

The UN’s International Year of Creative Economy for Sustainable Development concluded just days ago, so now is the ideal time to promote and understand the relationship between the informal economy and the cultural economy, as exemplified by India’s artisan sector. We believe that solutions for sustainable industrialisation and green growth in this and other sectors across the Global South lie in business models operating in the New Formal. Approaches that leverage the benefits of both formality and informality to boost the inclusion of informal creative communities already exist. With the right support, these enterprises have the capacity to deliver strong economic outcomes and greater social inclusion, while also pioneering new markets and fostering innovation. They just need to be recognised and supported.

Note: This article is based on Business of Handmade, an immersive, multimedia research project carried out by 200 Million Artisans exploring “The Role of Craft-Based Enterprises in ‘Formalising’ India’s Artisan Economy.” This study was commissioned by the Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre led by Nesta, and supported by the British Council.

Editor’s Note: This article was voted by readers as one of NextBillion’s Most Influential Articles of 2022.

Priya Krishnamoorthy is Founder and CEO, and Aparna Subramanyam is Partner at 200 Million Artisans; Anandana Kapur is a fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School.

Photo courtesy of rangSutra.

- Categories

- Social Enterprise