Seeking the Anti-Poverty Holy Grail: Can a ‘Trust Mark’ Boost Microfinance’s Social Impact?

Editor’s note: Throughout 2017, NextBillion is organizing content around a monthly theme, dedicating special attention to a specific sector alongside our broader coverage. This post is part of our focus on financial inclusion for the month of June.

Seventeen years ago, one of us compared the successful balance of financial sustainability and poverty reduction in microfinance to the Holy Grail – many searched for it, some claimed unconvincingly to have found it, and even more gave up on it as a beguiling myth. Not much has changed since then. Or so it may seem. Sophisticated research in the past decade has deepened doubt and strengthened skeptics. Yet practitioners, responding to moral imperative, societal need and market opportunity, keep trying to reach and serve people living in poverty. And many millions of them keep using microfinance. Why do they use it if it doesn’t help them? Do some practitioners do a better job of helping them than others do? How would we know?

Faced with this puzzle, a group of us set out in 2010 to find some straightforward way to identify the practitioners who are successful (and, by implication, those who are not so successful). But what does “success” look like? How would we know it if we see it? Depending solely on sophisticated (and expensive) research studies is not practical for sifting through a large number of practitioner institutions. So we asked: What are the obvious and essential practices of a “successful” practitioner that logic says should help clients achieve lasting, positive change that reduces or even eliminates poverty from their lives? If the logic is right, we should be able to quickly assess the “pro-poor performance” of various practitioners of financial services for poorer people.

The most obvious practice is to actively try to reach and serve people living in poverty. Of course! We can’t aspire to “lift people from poverty” if they are not living in poverty to start with. This became our Pro-Poor Principle No. 1.

The next most obvious practice is to design and offer products/services specifically to serve poorer people. This often requires segmentation of a diverse clientele to identify poorer clients and make sure at least some of our products/services are designed to address their particular wants, needs and constraints. This became our Pro-Poor Principle No. 2.

Less obvious, perhaps, is the need to investigate how the lives of participating clients actually are changing. This requires tracking the progress of clients (at least a representative sample) to understand how they use the products/services and how this use correlates with positive changes in their welfare (however the practitioner defines “positive change”). Such impact evaluation – bearing in mind that correlation points toward, but never by itself confirms, causation – serves more than donors/investors. It also provides vital feedback to the practitioner seeking to correct, improve and innovate products/services. This basic good business practice is our Pro-Poor Principle No. 3.

Armed with these three Pro-Poor Principles, we brought together microfinance rating agencies and other technical experts to design and test with us an assessment tool and process to tell us how completely a practitioner institution is adhering to the three principles. The more complete the adherence, the more likely the institution is truly helping people lift themselves from poverty.

To beta-test this tool and process, we commissioned three social rating agencies to assess nine institutions around the world, giving each a score composed from the answers to a number of questions about essential practices. We found that scores fell into four clusters along a continuum of potential scores.

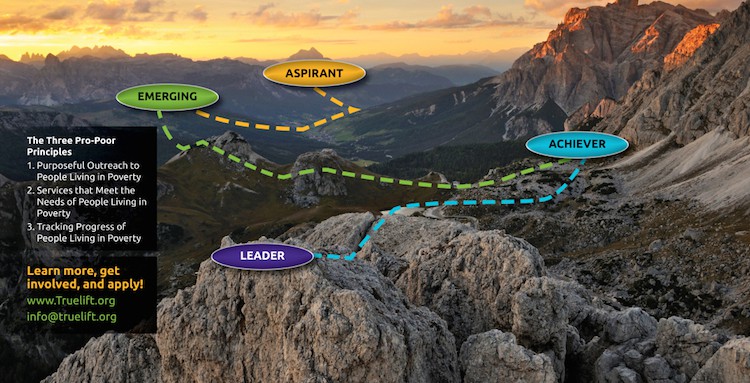

Even the most committed pro-poor institution is on a long journey toward “perfect” pro-poor performance and will never fully arrive. A threshold of “compliance” anywhere short of perfection would be arbitrary, so we decided it is better to recognize institutions as having arrived at milestones along a Pro-Poor Pathway. The four clusters of our beta test served to establish four milestones – Aspirant, Emerging, Achiever and Leader – ranging from those just getting started on the journey to those who have traveled a long way already and serve to inspire and encourage institutions further back.

Milestones on the Pro-Poor Pathway. Graphic courtesy of Truelift

These concepts and instruments offer the opportunity to create a global “trust mark” for anti-poverty action. There are many trust marks on which consumers, investors and regulators have come to depend for identifying quality in products and practices; for example, home care products, fair trade coffee, building design and forest products. We could have a trust mark for pro-poor performance that would build and support confidence in the pro-poor claims of development practitioners and service providers of many stripes, not just financial services.

Given the experience base of our group, we started with financial service providers in developing countries. We call ourselves Truelift (as in truly helping people lift themselves from poverty). So far, 24 microfinance providers reaching tens of thousands of clients have been assessed and recognized, each at one of the four Truelift milestones. In April, Truelift announced that Fundación Paraguaya in Paraguay and Friendship Bridge in Guatemala have reached the Leader milestone, the most advanced stage along the Truelift Pro-Poor Pathway. This recognition is based on the results of Truelift-licensed assessments conducted in late 2016 by MicroFinanza Rating.

Fundación Paraguaya and Friendship Bridge are only the second and third institutions to achieve the Leader milestone in Latin America and only the third and fourth in the world, respectively. This rarity reflects the difficulty of achieving the Leader milestone, but these institutions show that it can be done! The rarity also reflects the nascent stage of development of Truelift as a global trust mark signifying commitment to positive and enduring change for people affected by conditions of poverty.

To be in the same league as trust marks for fair trade commodities like coffee, Truelift must build the number of service providers recognized all along the Pro-Poor Pathway, to the point that donors, investors, regulators and others start to look for the Truelift milestone at which a practitioner institution is recognized – as a quick way to benchmark an institution’s progress and perhaps its worthiness for additional investment or other support.

The task would be easier if Truelift had been born in a sector other than microfinance. Several certification initiatives have arisen independently in response to lack of transparency and accountability regarding the social purpose of microfinance. The Smart Campaign attempts to identify providers that “do no harm” to clients by complying with the Client Protection Principles (CPP); even providers with no social objectives are included. For those with social objectives, the Social Performance Task Force has developed the Universal Standards for Social Performance Management (USSPM) without being specific about the social objectives of the provider. Social rating agencies offer assessments that can certify compliance with the CPP and the USSPM. But such compliance certification does not address how well the provider is achieving its chosen social objective. There are many social objectives to choose from, and some providers pursue more than one at a time. Truelift responds to the most common objective, poverty alleviation. A Truelift assessment is a logical extension to a social rating of compliance with the CPP and the USSPM by a provider focusing on poverty alleviation. Recently, these various global initiatives have been brought together by CERISE on the social performance assessment platform SPI4. Truelift is the poverty “module” of SPI4 along with modules for other specific social objectives. These modules can be used for institutional self-assessment or by rating agencies for external assessment of an institution.

In concept and structure, the Truelift Pro-Poor Principles and the assessment process are relevant and applicable to any poverty-focused (“pro-poor”) social business or service agency, whether private or public. We’re looking for opportunities to support assessment of a variety of service providers, not just financial service providers. Truelift has a small fund to co-finance or fully fund pro-poor performance assessments by its two licensed rating agencies, MicroFinanza Rating and M-CRIL. For additional information, please contact us, the co-chairs of the Truelift Steering Committee, Chris Dunford at christopher.j.dunford@gmail.com (English and French) or Carmen Velasco at carmenvelascolmk@gmail.com (Spanish and English).

Chris Dunford and Carmen Velasco are co-chairs of the Truelift Steering Committee.

Photo by Christopher William Adach via Flickr

- Categories

- Uncategorized