Customers as Partners: Medical device startup believes inclusive design process builds in loyalty, gives it a competitive advantage

“Human-centered design” is often thrown around as the next business trend for the American medical device market, but what does it mean to do human-centered design in a completely different cultural context?

Sure, it makes sense that the devices we interact with on a daily basis are built with some feedback from us concerning their use, but previous design thinking often was less intent on meeting customers’ actual needs than on increasing sales and the firm’s technical ability. Most do this by asking categorical questions: How much does it cost? How many features does the customer want? Few companies actually focus on their customers’ purpose for the product and the observations that could be vital to redesigning that device. Add to that an FDA regulation or other difficult governmental hurdle, and most design is created to speed the immediate business runway.

Human-centered design can make sense in the ever-changing U.S. market, but is even more important in developing markets, which require a variety of perspectives and empathetic views before companies can even dream of entering. In a different cultural context, such as Sub-Saharan Africa, the purpose of a product and how it’s received can be lost despite training or educational sessions. The exception is when end users are able to collaborate on the creation of the product or service. Their expert understanding of the purpose for the product cannot be matched and they will often help drive demand.

Human-centered design has helped open a previously ignored market: Africa. The burgeoning medical device market in developing countries has drawn the likes of Medtronic, Covidien and Becton Dickson, but is also a ripe place for startups with more flexible core strategies.

My company, Sisu Global Health, is seeking to take advantage of this trend of African growth and consumer need. We have a double bottom line approach – profits and social impact – in offering medical devices specifically tailored toward African hospitals and clinics. We are bringing in customers as actual partners of the designs, to help critique, test and analyze how our devices can better serve their needs – even at the sacrifice of some profit.

My company, Sisu Global Health, is seeking to take advantage of this trend of African growth and consumer need. We have a double bottom line approach – profits and social impact – in offering medical devices specifically tailored toward African hospitals and clinics. We are bringing in customers as actual partners of the designs, to help critique, test and analyze how our devices can better serve their needs – even at the sacrifice of some profit.

(Kennedy Sakyi, biomedical engineer at Tettah Quarshie Memorial Hospital in Ghana, left, with Kirsch.)

Our first device that demonstrates human-centric design is the Hemafuse. The Hemafuse is designed to transfuse blood – not from someone else’s voluntary donation but, in emergency cases, from the patients themselves when other blood isn’t available.

Emergency doctors in Ghana and other parts of Sub-Saharan Africa frequently see traffic accidents and pregnancy complications that they are unable to treat because they cannot access needed (donated) blood. We hope to solve this problem by allowing doctors to reallocate internally hemorrhaging blood back into the patient. This prevents issues of transferring disease and rejecting donated blood – which are problems as much in the U.S. as in African hospitals.

Sisu learned of this issue after four years of independent trips to hospitals in Ghana. The team has traveled to the major hospitals in Kumasi, Tamale and Accra. Gillian Henker, our chief technical officer, observed the procedures of OBGYN and emergency doctors and has taken multiple prototypes of our devices for critique. Our partners at Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital, Korle Bu Teaching Hospital and the Ministry of Health have been with us since the beginning of the company. They have as much stake in the Hemafuse as we do, and tell us they desperately want to see it brought to their surgical theaters.

Many medical device companies (and some aid agencies, for that matter) do not seek out the advice of the doctors using the devices. The fact that we do gives us immense advantages with our customers; we have loyal relationships that began with design, not the sale.

Many medical device companies (and some aid agencies, for that matter) do not seek out the advice of the doctors using the devices. The fact that we do gives us immense advantages with our customers; we have loyal relationships that began with design, not the sale.

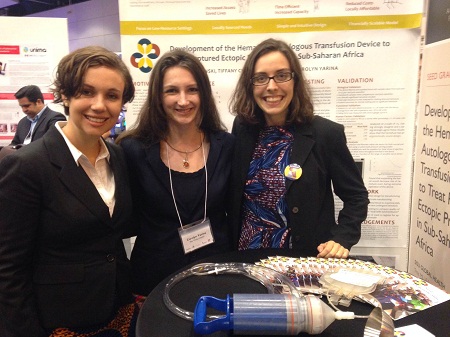

(The Sisu team at the Saving Lives at Birth: A Grand Challenge for Development competition earlier this year, where they won a $250,000 grant; left to right, Kirsch, CEO Carolyn Yarina and Henker.)

These relationships enable us to not only design a great product, but to effectively scale. Some of our major champions in the country are at teaching hospitals. These institutions train the next generation of doctors, meaning that if the Hemafuse becomes a standard piece of equipment in these hospitals, trained doctors will begin to demand it in other hospitals.

That initial demand is also the beginning of the procurement process for government and most private hospitals. We intend to let our human-centered process lend itself to scalability outside of Ghana as well, as we continue to seek out blood transfusion experts in each country to both advise and support our international scaling.

With the intent to scale internationally, we specifically chose to be a for-profit social enterprise based in Southwest Michigan – a medical device hub with deeply embedded philanthropic values. This choice came after more than a year of deliberations. But it can still pose a significant obstacle: How do we approach potential funders? We do not want donations. We want the funder’s investment to be a sustainable return that they can reinvest in ours or other initiatives. Returns on these investments will take a little longer, but will make a greater impact in the long run.

Human-centered development is at the very heart of Sisu Global Health’s design and business model. Not only do we view independent sales transactions as more than just the exchange of money, we firmly believe that by creating a product for sale, and not for donation, we give people a choice. Simply put, there is dignity in choosing to buy a product – one that helps ensure the continued use of the product for its intended purpose. A product that is intentionally bought requires a rational decision to weigh the costs and benefits of the purchase. This posture firmly fits within Sisu’s vision to utilize market-driven motivations compared to channels of charity.

Human-centered development puts those customers within reach who would otherwise never be a part of the design and business process.

Katherine Kirsch is the chief marketing officer of Sisu Global Health.

- Categories

- Environment, Health Care

- Tags

- product design