The Economic Lives of Sex Workers: Can Financial Inclusion Offer Women a Path Out of the Sex Trade?

Four years ago, at the age of 20, Rosa came to the New Town neighborhood of Accra, Ghana, from her home in the Volta region. With her high-school diploma, she found work as a secretary. However, her position was soon retrenched and, desperate for money, she took the advice of a new friend who showed her how to earn a bit of money as a sex worker, on what Rosa thought would be a temporary basis.

Rosa’s is not an unusual story, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa where sex workers in urban areas can represent as much as 4 percent of the adult female population. If we include those women who occasionally have to engage in sex for money, the share climbs to 9 percent of adult women, around half of them under 30. In total, about 7 million women perform sex work in the region, based on a total of 282.6 million adult females in sub-Saharan Africa and an average sex worker prevalence of 2.5 percent.

Rosa’s is not an unusual story, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa where sex workers in urban areas can represent as much as 4 percent of the adult female population. If we include those women who occasionally have to engage in sex for money, the share climbs to 9 percent of adult women, around half of them under 30. In total, about 7 million women perform sex work in the region, based on a total of 282.6 million adult females in sub-Saharan Africa and an average sex worker prevalence of 2.5 percent.

Like so many, Rosa has financial needs and goals. Women like her need formal financial services even more than many other entrepreneurs because they largely deal in cash and often work in physically insecure environments. She experiences frequent cash inflows and is saving to buy something that will help generate a new income. In short, she needs her own portfolio of financial instruments to allow her to fulfill her plans. Like many sex workers, she has a clear financial target—finding a safer and more dignified livelihood—that provides a focus for her use of financial services.

The Economics of Sex Work

In her current life as a sex worker, Rosa serves up to five clients a night in the New Town area, earning between 15 and 20 Ghanaian cedi or GHc (about US $3.25 – $4.35) per customer. Sometimes, when desperate, she will decrease her price to 10 GHc, or US $2.20. On Saturdays, Rosa takes advantage of weekend crowds in the entertainment-oriented Labadi area to solicit foreign customers, who will pay higher prices of up to 70 GHc (US$15.22) each. On those nights, she needs to invest in transport to Labadi, and she cannot take her hired security guard with her since she is working in customers’ hotel rooms. She has less control of the situation, but the risks are worth it: She earns more in one night in Labadi than in three in New Town.

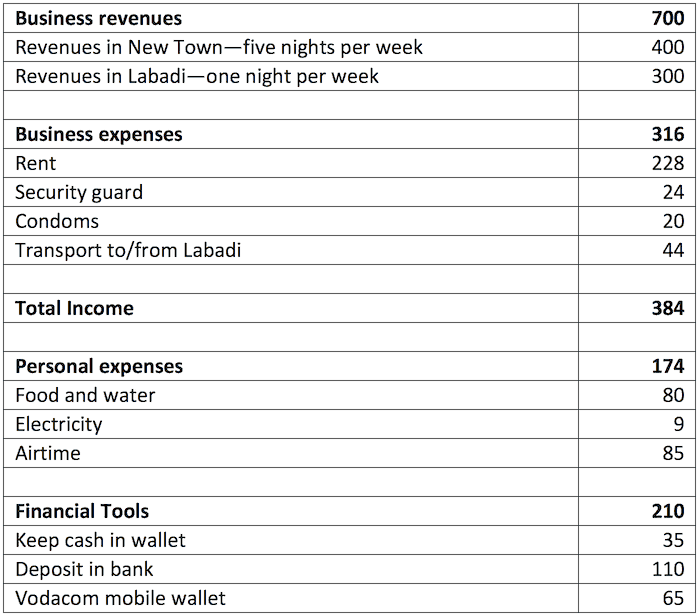

The following table shows Rosa’s income, expenses and savings over the course of a week, and points to her existing use of three financial products: cash, a deposit account and a mobile wallet:

The economics are clear, even after all the extra expenses Rosa undertakes for personal security, including:

- Renting a high-priced room with an en-suite private bathroom for 35 GHc (US $7.61) per night;

- Hiring a security guard for 5 GHc (US $1.09) per night; and

- Spending 20 GHc (US $4.35) a week on condoms, as she refuses to work without them.

Rosa is well aware of the risks she faces, such as HIV/AIDS and physical attacks. These measures, along with aggressive, clear and purposeful planning, are her insurance for the future.

Even after netting out expenses, Rosa earns more than US $360 a month. This is twice as much as the median monthly earnings of casual workers in Ghana (US $190 per month) and certainly more than other types of low-income work in developing countries around the world. BFA’s Financial Diaries provide other examples for comparison: A farmer in Western Tanzania selling potatoes makes only US $670 a year (or US $56 per month, if the income were evenly spread over the months, which it is not). A teacher in a rural Kenyan secondary school earns about US $60 a month. A city-based dosa seller in India makes about US $80 per month. Even a construction worker in Mexico earns only US $200 per month. One man we met who works at the Kenya Ports Authority in Mombasa earns an average of US $933 per month, but he completed high school and has worked there since 1991. Few other forms of work are open to Rosa that can bring in a comparable income.

Helping Sex Workers Plan for the Future

Even so, Rosa is acting on her plans to escape sex work. Saving steadily US $175 every month in her bank account and mobile wallet, even while taking out money for clothes on a regular basis, she has already saved 500 GHc (US $109) to buy a shipping container from a trusted client, which she plans to convert into a store to sell cosmetics in Labadi. She is now working to save the 2,000 GHc (US $435) she needs to buy stock for the shop. Rosa plans to bring a cousin to Accra to learn a trade and assist with the shop. Her cousin will run the shop and live in the container while Rosa continues to do sex work. Once Rosa saves enough to rent an apartment for the two of them (she needs to pay a full year’s rent in advance to rent an apartment in Accra), her cousin can start to assist while Rosa works full time in her shop.

Rosa’s strategy includes clear financial planning that point to ways that financial inclusion can help her and others like her create a path away from the sex trade. First, she saves about 20 GHc (US $4.35) every day in her apartment, bringing the cash to a nearby bank branch every five days. Second, she saves 10 GHc (US $2.17) every night in her mobile wallet, using an agent close to her room. Previously, she used a susu collector, an informal, traditional financial intermediary who holds client savings for a fee. But she decided that she didn’t trust the collector and wanted to be more in charge of her own savings. While these methods are a good start, financial services that would allow her to save and even borrow could enable her to start her shop earlier and minimize her exposure to the dangers of her current profession.

Rosa’s story suggests the need to focus on the “inclusion” aspect of the financial inclusion movement even more than we do today. Women like Rosa are striving to create better lives, and only want the same chances to use the financial tools and services offered to others. Financial institutions, like the Usha Multipurpose Cooperative Society in Kolkata, India, are beginning to recognize that the economic lives of sex workers like Rosa have the potential to turn into more sustainable livelihoods, making them attractive customers as well. However, financial institutions that see their services purely as charity to sex workers are not always sustainable – for instance, the Sangini Cooperative Bank in Mumbai closed their doors in 2017 after a period of offering interest-free loans. This suggests that mainstream financial services simply need to see the value in an overlooked population.

Daryl Collins is CEO of BFA.

Image credit: Onny Carr via Flickr.

Homepage image credit: vinylmeister, via Flickr.

- Categories

- Uncategorized