The Key to Fighting Poverty in Africa: Could unlocking smallholder finance solve both the continent’s food and employment challenges?

Social lenders such as Root Capital have pioneered financing for smallholder producers of export crops like coffee, cocoa and tea. Now, Root is seeking to help build agricultural businesses that serve local staple crop markets as well – a financing market that may be 10 times as big.

Root, together with Germany’s KfW Development Bank and agriculture impact investor AgDevCo, recently announced the Lending for African Farming Company (LAFCo), a $15 million facility to provide working capital loans to the small and mid-sized businesses that supply and buy from Africa’s smallholder farmers.

“It may still take another decade before it’s at the point where commercial capital flows in significant volumes,” said Chris Isaac, AgDevCo’s investment director. “Blended finance structures like this, managed by investment professionals, can help bring in more capital earlier which will have a massive developmental payoff.”

Small and mid-sized agribusinesses are a vital link in Africa’s local and regional agriculture markets. For smallholder producers, the vast majority of Africa’s farmers, such businesses buy harvests, transfer knowledge and procure inputs in bulk to help drive down farmers’ costs.

These businesses also are key to building an inclusive African economy able to absorb a workforce that’s set to double in size over the next 25 years and to feeding a continent that is hungrier now than ever. In Africa, growth in agriculture can be 11 times more effective in reducing poverty than growth in other sectors.

There’s only one problem: Commercial banks won’t lend to them.

Financing Gap

Agriculture is a risky business. And in Africa, it’s riskier. Poor infrastructure, especially in rural communities, drives up costs. Weather is erratic, unpredictable and a persistent agriculture-related risk. Most investment opportunities in African agriculture are small. That makes it hard for deals to turn a positive financial return due to their high due diligence and legal costs. Commercial banks can get similar returns in other investments with less risk, and less work.

“Even when (commercial banks) look at businesses with two or three years track record, branded products and off-take contracts, they often prefer to wait and see for another two or three years before coming on board,” says Isaac.

For producers of export crops with solid purchase agreements, Root Capital and other social lenders lend through producer associations that make disbursing funds more efficient and less risky.

For producers of export crops with solid purchase agreements, Root Capital and other social lenders lend through producer associations that make disbursing funds more efficient and less risky.

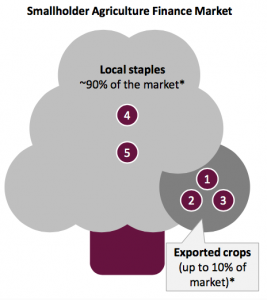

Dalberg Global Development Advisors estimates that social lenders and local banks are now meeting roughly half of the $22 billion financing gap for such export crops.

But this is only 10 percent of the smallholder market. The bulk of smallholder finance needs lie in local markets that trade in surplus staple crops like wheat, maize and cassava. That represents a huge financing gap, primarily in Africa, Asia and Latin America.

Dalberg helped develop LAFCo’s financial and impact models and investment thesis. On a global scale, the consulting firm estimates that the demand for capital from the 90 percent of smallholder farmers that sell into local markets is in the range $500 billion. Only 3 percent of such financing needs are currently being met. The financing need may be two to three times as large when adding in the small and medium-sized businesses that work with these farmers, Root Capital notes.

Filling that gap would benefit farmers that would have a reliable market for their crops, prepared to pay fair prices, or access to better quality input seeds and fertilizers from a trusted supplier.

Blended Capital

Donor funds can’t fill the gap. LAFCo’s public and philanthropic investors came together to create a facility that would allow their commercial peers to participate by mitigating the investment risk.

LAFCo will walk a fine line. It doesn’t want to compete and crowd out the local banks. It’s not offering cheap finance, its terms are commercial.

“It’s about proving you can (provide working capital to African agribusiness) profitably,” says Isaac. “We want to show that with the right products and the right expertise and the right people on the ground, there is business to be done here.”

KfW, with funds from the German government, provided an $11.6 million anchor equity investment into the facility. AgDevCo, backed by the UK government and a number of private foundations, added $2 million. The two equity investments help mitigate the risk to debt investors. Root Capital will manage the facility and provide $2 million in subordinated debt.

There’s as yet no senior debt investor in the blended capital model. But ImpactAlpha has learned a prominent social lender is conducting their underwriting and is hoping to join LAFCo this fall.

Demonstration Effect

The partners’ local networks and market expertise are the key to deploying capital effectively. KfW has been active in agriculture finance for decades, structuring and launching the Africa Agriculture and Trade Investment Fund, the Fund for Agricultural Finance in Nigeria and the Fairtrade Access Fund.

AgDevCo has provided financing for African agribusinesses since 2009. With a $150 million portfolio it often takes the “front end” risks involved in investing in agribusinesses at an early stage. “Unless someone’s going in and building those businesses from the ground up, there simply won’t be a pipeline for the larger impact funds, the development finance institutions or, indeed, private equity to invest in,” Isaac says.

Root Capital, best known for its export trade-financing model, in 2011 launched its Frontier Portfolio to focus on the gap in finance in local and regional markets. Today the strategy represents about 10 percent of Root’s $114 million overall portfolio, giving Root valuable expertise in developing appropriate credit products, training staff, and building a deal pipeline in Africa’s regional and local agri-markets.

LAFCo plans to do about a half-dozen investments this year and then 10 to 12 per year. The initial targets will be in seven countries where AgDevCo and Root have overlapping operations: Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Senegal, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia.

With a successful track record the partners hope the vehicle can attract $50 million within three to five years and eventually hundreds of millions. Over 10 years LAFCo has the potential to reach a million smallholder farmer beneficiaries, Isaac says. LAFCo’s “demonstration effect” may encourage local commercial banks to enter the market directly as well.

“Much of the risk in local agriculture markets is real. But a lot of it is perceived,” says Nate Schaffran, Root Capital’s senior vice president of lending. “What we’re trying to do here is demonstrate the appropriate level of risk.”

This blog first appeared on Impact Alpha. It is reprinted here with permission.

Dennis Price is a contributing writer for Impact Alpha.

- Categories

- Agriculture