Unite Behind the Science: When it Comes to Cooking, it’s Time for ‘Clean’ to Mean Something

Ever since she burst onto the global stage in pigtails and furrowed brow, Greta Thunberg has been freaking out the fossil fuel lobby and its allies––with good reason. The power of her message comes from its simplicity: the facts on climate change are irrefutable, and we should all unite behind the science and take the actions needed to stave off the worst impacts.

It’s time for similar clarity and action around clean cooking. This week, the Clean Cooking Alliance is hosting their stock-taking bi-annual global conference. And yet, in spite of great new energy and incredibly hard work, we’re still making virtually no progress toward meeting the ambitious goals of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 7 to deliver “access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all” including cooking, by 2030.

Currently nearly 3 billion people live in homes where someone burns sticks or charcoal or dung to cook – every single day. This Stone Age approach is devastating to their health, their local environments and the climate. And it’s getting worse: Spiraling demand for charcoal, driven by mass migration into cities (where gathering wood is less feasible), is destroying landscapes across Africa.

No More Blue Ribbons For Trying

Yet after decades of failure by literally thousands of cookstove “projects” to deliver truly clean cooking to the masses, the problem seems just as intractable as climate change. Millions continue to die each year from breathing toxic smoke, day after day, as tons of carbon pour into our atmosphere.

Why is this problem so difficult to solve? In part, it’s because for far too long, the clean cooking sector has been burdened with a “blue ribbon for trying” approach, wherein even projects with marginal impact get written up as “cleaner” and “improved” – as though they’re the ideal solution.

The word clean has a very specific meaning: “free from dirt or pollution.” Yet it’s been used for so long to describe so many projects that in fact are not clean, that the word has essentially lost all meaning. That’s one reason why the cooking sector long ago collectively lost all credibility with funders in the public health arena. This is painfully obvious, as we see so few health officials attending cooking sector conferences, and practically nothing in health funding directed to the cooking sector for many years.

This instinct to support any progress is understandable, given the scope of the cooking development problem and its woeful lack of financial and policy support. It’s true that some “improved” cookstoves reduce fuel needs and household air pollution (HAP) emissions by 50% or more, which does improve life for their users. It’s also true that these stoves benefit forests and the climate, and reduce the “time poverty” associated with gathering fuel. Yet, even with those improvements, these stoves barely move the needle on health outcomes.

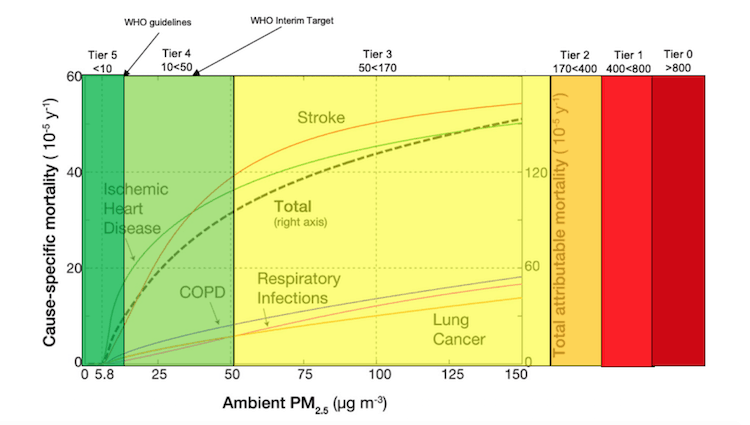

Health researchers have long known that the relationship between household air pollution and the associated risk of disease is not linear. The hard truth is that cutting HAP exposure by even 75% compared to three-stone cooking yields only a small reduction in the risk of smoke-induced disease. The public health funders understand this and thus have withdrawn from the playing field. This is not to criticize the dedication and incredibly hard work of the many people working on these clean cooking projects. Rather, it is to acknowledge just how tough a nut this is to crack.

The line in the sand that international experts (i.e. the World Health Organization) have drawn for “healthy” levels of exposure to small smoke particles (PM 2.5) is 10 micrograms per cubic meter, with an interim target of 35 micrograms per cubic meter. Anything above that is simply not healthy. Cooking with solid fuels on open fires – even over many “improved” cookstoves – still has a baseline HAP exposure comparable to breathing the second hand smoke of several hundred cigarettes. The ”airpocalypse” happening right now in New Delhi isn’t far removed from many families’ daily kitchen experience.

In fact, HAP exposure must be reduced by 95% or more to bring health outcomes into the range that should be deemed acceptable. This probably explains why, in a donor world awash in several hundred million – or even multi-billion – dollar public health investments from big funders like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, there’s a scandalous lack of money going into clean cooking. A humbling Energizing Finance report released by Sustainable Energy For All last month showed that less than 1% of the funding needed to reach SDG 7’s universal clean cooking goal is being invested, and that global investment in the clean cooking sector is actually decreasing.

The health sector, which should be a wellspring of investment, has been burned too many times by cooking projects over-committing and under-delivering on health benefits. If we’re going to get their billions off the sidelines and into the fight, we’re going to have to deliver dramatically improved outcomes, and be able to prove it.

What clean really means

Luckily, there’s a clear roadmap to follow: a ranking system of six Tiers. Developed by the International Organization for Standardization, in partnership with the Clean Cooking Alliance, this Tier system offers an easy-to-understand explanation of what is – and isn’t – “clean” cooking. The lowest Tier (zero) is the dirtiest, while Tier 5 is the cleanest.

For too long, these Tiers have existed as labels without teeth, like having clean air standards on the books with no one to enforce them. But the science is clear: Anything less than Tier 4 isn’t going to deliver significant health benefits, and Tier 4+ can make a huge impact on health outcomes.

Historically, few fuel+stove combinations have met the Tier 4 threshold. (To see the Alliance’s Clean Cooking Catalog with stove ratings, click here. Most are Tier 1 and 2.)

The mortality rates for diseases attributable to ambient particulate matter (PM), adapted from the original, available here. Most “improved” cookstoves being deployed today yield particulate exposure in the right hand side of the graph, Tiers 1 to 3, posing significant health risks.

Fortunately, there’s been a fast-emerging trend of “fuel+stove” business models, which combine the use of renewable fuels with super-clean stoves. By bundling fuel and stove into a single offering, the best stoves are made affordable, solving the dilemma posed by Kevin Starr of the Mulago Foundation: “The cheap stoves aren’t good enough, and the good stoves are way too expensive.” Earlier this year, a broad-based coalition of researchers, practitioners and advocates joined up to both note these breakthroughs and issue a clarion call for broader support of these low-cost, renewable offerings.

There are now a multitude of companies operating successful fuel-based, renewable energy cooking solutions, including Sistema Bio (winner of this year’s Ashden Award), Koko Networks, Emerging Cooking Solutions, and our own Inyenyeri. These are Tier 4 and 5 clean cooking solutions delivering substantial health, climate and environmental benefits.

Best of all, these are solutions with proven impact. In the last few months, multiple independent, peer-reviewed scientific papers have been published that demonstrate that super-clean cooking with renewable fuels is not only possible, but also achievable at a much lower cost than previous attempts. For example, a study released this summer showed pellet gasifiers deliver emissions performance comparable to liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) – the most commonly cited “clean” cooking option. The study found “>90% reductions in most pollutant emission factors/rates from pellet stoves compared to baseline stoves.” It concluded that “pellet stoves have the potential to provide health benefits far above previously tested biomass stoves and approaching modern fuel stoves, e.g., LPG.”

Another study showed that users of these new cooking solutions were both richer and healthier relative to people who use traditional fires or “less clean” types of cookstoves.

So if we know there are proven clean renewable options, how do we get them more widely adopted?

A Path Toward Truly Clean Cooking

Using the Tiers as a way for funders and other stakeholders to identify and support providers with the most proven impact is a pathway to addressing this dilemma, and bringing in the massive investment needed to achieve universal clean cooking objectives. Governments, investors, aid institutions and other market influencers should align their support and incentives with the science behind the performance of different cooking solutions.

With smart, targeted and science-based interventions, we can finally start delivering on the promise and potential of SDG 7 for clean cooking. Here are some steps we can take, all of which need to be mapped to an aggressive timetable if we have any hope of meeting SDG 7 by 2030:

- Regulators should require that any “improved” cookstoves sold in their country meet minimum WHO levels of performance – in the field as well as the lab. Ban Tier 1 products by 2022 and Tier 2 products by 2025.

- Government incentives, in the form of reduced import tariffs, direct subsidies or other interventions, should be explicitly linked to the emissions performance of stoves. Give more generous support to the cleanest products.

- Donors and impact investors should immediately reduce or stop investment in projects that promote low-performance stoves, and increase investment in efforts that deploy higher performing products. Create explicit near-term goals for the share of investments directed to Tier 3+ solutions, and by 2025 support only Tier 4 and 5 systems. The World Bank’s newly-announced $500 million Clean Cooking Fund could set the table for this approach.

- Carbon credit buyers should set a baseline level of health performance for projects to even qualify for their portfolio, and then pay a premium per carbon credit based on the HAP reduction the product offers.

- The Clean Cooking Alliance could continue the leadership it has shown in establishing the Tiers, by using their convening authority to establish a timeline for adoption of minimum performance by its member groups and projects, ratcheting up annually until all are minimum Tier 4 or better.

As this approach gains traction, the combination of stove ratings and differential incentives from institutional and government players will tilt the market toward ever-higher levels of performance.

The science on health, and on climate, is crystal clear. The status quo isn’t good enough, and we all know it. For the sake of humanity and the planet, let’s take the path we know is right, and follow Greta in uniting the clean cooking sector behind the science.

Eric Reynolds is the founder and CEO of Inyenyeri.

Photo provided by organization.

- Categories

- Energy, Environment, Health Care, Social Enterprise