Water, Water Everywhere: How Clean Is It Really?

Editor’s note: This week we feature a four-part series analyzing community-scale water solutions using the 5 P’s framework: Population, Problem, Product, Process, and Partnerships. The series was contributed by researchers from the Rural Market Insight team at the Centre for Development Finance (CDF), who recently spent a month in Rajasthan discovering Base of the Pyramid consumer preferences for treated water.

We encourage you to engage in the discussion by adding your comments and questions to the posts. You can also participate in Ask Acumen, which this week offers the opportunity to learn more about Acumen Fund’s work with social enterprises that address water-related challenges.

How do we know that our soap contains “no harmful chemicals” or our vegetables are fresh? During a drought, how do we distinguish water quality from quantity? Likewise, how do Base of the Pyramid (BoP) consumers know that the filtered water they buy is really pure? Purity must be clearly delineated in order for BoP consumers to truly understand and value the quality of clean drinking water.

An old German proverb states, “In wine there is wisdom, in beer there is freedom and in water there is bacteria.” Sadly this is more than adage, but rather it’s reality for many in developing nations, where 98% of the world’s water-related deaths occur. It is generally estimated that 1 billion people lack access to safe drinking water, resulting in more than 3.5 million deaths each year from water-related diseases. That translates into more than six people each minute, 84% are children.

Purity means different things to different people, which we learned on our one-month journey through villages in northeastern Rajasthan (insert link to blog #1). For Sarvajal’s filtered water customers, purity is obvious. To Mamta from Chirawa, it means her lentils cooks faster and saves her money on cooking fuel. To Veer Singh from BanGothodi, it means his joints no longer ache. And Banesh, also from Chirawa, can just “feel in his heart” that it is clean.

For non-users, filtered water’s purity isn’t infallible. To Ramnath from Rolsabsar, the water is sour and its taste changes frequently. To Karan from Chirawa, the bottles are dirty and delivery seems unreliable. Indian Administrative Services officer from Chirawa, told us that he believes filtered water made him gain weight due to the “pesticides and hormones, like estrogen” he believes are added during the purification process.

Beyond the anecdotal, water purity can be certified by electrolysis equipment, quality control testing at the source and point of delivery and printed on packaging. It is measured in parts per million for total dissolved solids (TDS) or fluoride content and biological impurities. Yet, non-users in our interviews and focus groups questioned filtered water’s purity by slight changes in taste (which often happens due to weather changes) or even the appearance of the bottle in which it was delivered. Purity, it turns out, has become subjective among consumers in rural Rajasthan.

(Above: “Why should we support (the entrepreneur]? If the government sets up a plant then we’ll definitely use it,” proclaimed one of the villagers of BanGothodi. Distrust of private and individual business owners was common in the small villagers we visited).

From person to person, we encountered several attributes and factors that affect individual assessments of purity, which in turn impact decisions to purchase (or not purchase) filtered water, and thereby influence sales. Purity depends on a multiple factors, especially:

- Taste – Sweet taste, or the opposite of “sour,” was favored in most scenarios. High priority was placed on consistency of taste. Taste often came before any other attribute, including appearance.

- Health impacts – Varying importance placed on immediate versus long-term effects. Outward physical effects were the most common complaint.

- Appearance – Color of water or residue left from water was an easy attribute to detect. Not surprisingly, clean, sealed and labeled bottles were looked upon favorably.

- Source – Quality of the original source of water was questioned. Many were wary of individuals or those in the “business” of water. NGO and government plants were praised.

- Methods – Most were unaware of how water is purified, the technology used or who operated the machines.

- Terminology – There is no consistent terminology. Much confusion exists about substances found in water, acronyms describing them and the measurements used to communicate quality.

- Ecosystem – Having water at home was only one part of the puzzle, constant access – at school, work and in town – was key. Institutional support from both government and private hospitals and schools seemed influential.

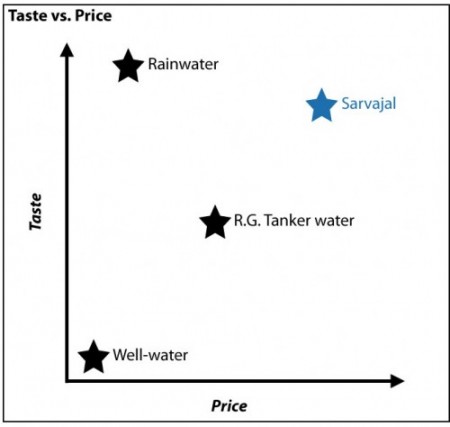

For example, in the village of Ramsisar outside of the town of Fatehpur in Rajasthan, local villagers had many options for water – well water, a tanker supply from a nearby village, rainwater collection and Sarvajal filtered water. Our research showed that while well water was the cheapest option, it also tasted the “worst” compared to rainwater, which was considered the tastiest, but was seasonal and carries high infrastructure costs. The tanker supply was a happy medium, tasty and reasonably priced, and therefore becoming a more popular choice than Sarvajal water, which was the most expensive option and tested slightly under rainwater in taste. Whether or not the tanker supply was filtered, clean or safe had little impact on purchase decision. Instead, decisions relied most on taste.

(Above: A diagram of pilot study learnings on BoP consumer preferences for taste vs. price in villages in Rajasthan. Taste was one of the most influential attributes driving purchase decision).

Researching customer preferences uncovered the dire trade-off BoP customers must make for immediate health impacts. It was well known that well water causes diarrhea and other illnesses during the summer, when water levels were low. Many villagers opt for other sources of water, like filtered or tanker water, and then return to local water when the monsoon started. Villagers were not selective with other water sources as long as the immediate health issues were solved with the alternative. They were happy drinking rainwater, tanker water or Sarvajal water as long as they were not having symptoms of diarrhea. The long-term health effects of impure water were often overlooked or misunderstood.

In essence, we realized that explaining the product and outlining the process were key to defining purity for potential BoP consumers. Social entrepreneurs can eliminate the subjectivity around purity, an important element of the water crisis. Once these attributes are addressed, consumers will perceive purchase value and communicate to others: clear product value and benefits will spur word-of-mouth marketing in the BoP.

If consumers are not convinced that the water they drink is pure or do not understand the filtration process, how can they be expected to drink it? Unless water companies, governments and investors solve this problem through targeted outreach and effective marketing strategies, it might be wiser, and even safer, to reach for that glass of wine. After all, there is truth in the wine.

Special thanks to David Fuente, Geetanjali Shahi, Bree Bacon Woodbridge, and the team at Sarvajal for their help throughout this series.

- Categories

- Agriculture, Health Care