Weekly Roundup – 11-9-13 – For Sale: Your Future: Should young people sell shares of their future earnings to investors?

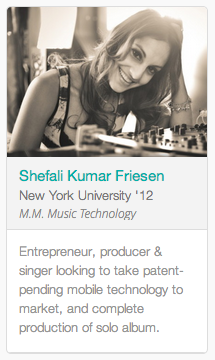

Take a look around upstart.com. You’ll see glossy photos of smiling young go-getters in dynamic poses, followed by a brief blurb explaining why they’re asking for your money:

Ian Shakil is a “Stanford MBA building a Google Glass application for healthcare.”

Cynthia Salim is a “Rotary Scholar and McKinsey hire ready to launch an ethical clothing line.”

Francisco Garcia is a “Vanderbilt graduate opening a restaurant in Brooklyn and seeking to retire student loans.”

Upstart is a crowdfunding company founded by former Google employees. It allows investors to fund other people’s careers, in exchange for a percentage of their future earnings over either five or 10 years. There’s no age limit to the service, but it’s geared toward young people in the U.S. who are struggling with the cost of college – funding is only available to people who graduated (or will graduate) between 2005 and 2015.

Upstart isn’t the first to develop this kind of a product, which economists call a human-capital contract. And they certainly won’t be the last to apply it to the problem of student debt. Other U.S. companies, are doing similar things, as are counterparts in countries like Germany, Colombia and Mexico. The demand is clearly there: U.S. students carry a loan debt that’s approaching $1.2 trillion, thanks to the skyrocketing cost of college and dwindling government funding for education.

When I first heard about this approach, I had mixed feelings. Asking heavily indebted young people to sell a percentage of their earning potential to a group of investors just seemed kind of … creepy, for lack of a better word. And this isn’t a first-world version of Kiva, the well-known non-profit provider of crowdfunded microloans for the poor, which allows anybody to lend small amounts to recipients around the world. (Incidentally, for the last few years, Kiva has closely partnered with Vitanna, a crowdfunding site that says it has provided loans to more than 6,000 students in 12 countries since 2009). Upstart is only open to accredited investors, ie: those with a net worth in excess of $1 million, or a stable income that exceeds $200,000/year. They’re viewing students as investments that will (hopefully) produce returns. So the power differential between investors and investees struck me as troublesome – especially since both parties are linked, with photo profiles, on the site, with investors encouraged to interact with and serve as mentors for their investees.

When I first heard about this approach, I had mixed feelings. Asking heavily indebted young people to sell a percentage of their earning potential to a group of investors just seemed kind of … creepy, for lack of a better word. And this isn’t a first-world version of Kiva, the well-known non-profit provider of crowdfunded microloans for the poor, which allows anybody to lend small amounts to recipients around the world. (Incidentally, for the last few years, Kiva has closely partnered with Vitanna, a crowdfunding site that says it has provided loans to more than 6,000 students in 12 countries since 2009). Upstart is only open to accredited investors, ie: those with a net worth in excess of $1 million, or a stable income that exceeds $200,000/year. They’re viewing students as investments that will (hopefully) produce returns. So the power differential between investors and investees struck me as troublesome – especially since both parties are linked, with photo profiles, on the site, with investors encouraged to interact with and serve as mentors for their investees.

(Left: a profile of an Upstart investee)

But then I got to thinking: for young people, monetizing their future earning potential can make financial sense. Student loans are often fixed-payment debts, while products like Upstart allow them to pay investors at an adjustable rate, which varies depending on how much they earn. If their Upstart financing lets them advance their education or jump-start a business (granted, that’s a pretty big “if”), it’ll be much easier to pay off their investors once their careers get off the ground than it is to start paying off their student loans during their 20s. And there are some safety mechanisms built into the product: payment obligations are capped, so even successful investees won’t end up paying over three to five times the funding amount they received. Payments are waived for years in which they earn less than a minimum income amount (with an additional year added to the agreement – up to a five year maximum). And if they can’t pay off their investors, the unpaid amount is converted to a fixed rate, fixed term loan. So they’re not exactly selling their souls.

Besides, with the average U.S. college graduate holding close to $30,000 in student loans – and often much more for those who go to grad school – we need innovative financial products to help them out. There’s also a strong potential social impact to giving bright young people the opportunity to start businesses or develop new technologies that could benefit (and employ) many others – rather than just taking the first job that comes along in order to make their loan payments.

What do you think? Is it exploitative to purchase a share of a young person’s income? Or is it just what the market needs? Could a similar approach be used to help other low-income communities, in or outside the U.S. – or would that cross a line? Expect these questions to come up more frequently: with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission’s recent announcement of new rules that will make it legal for non-accredited (read: non-wealthy) investors to invest in startups and entrepreneurs, we may be seeing similar approaches in the coming years.

Editor’s note: NextBillion Financial Innovation is broadening our coverage area to include low-income groups in the U.S. – so look for more posts on initiatives and innovations geared toward these communities in the coming weeks.

In Case You Missed It … This week on NextBillion

NextThought Monday: Want to end poverty? Bring financial education and empowerment to the youth, says Jeroo Billimoria By Jeroo Billimoria

An Inclusive Business Executive Education : A new program to bring out innovation and change By Stephanie Schmidt

Solving a $2.5 Trillion Problem: Can innovations in credit scoring give credit where it’s due? By DJ Didonna

Econ 101: Three different ways to lift girls out of poverty By Betsy Nolan

A Farewell to Cash?: The move toward a cashless world – and what it could mean for the BoP By James Militzer — WDI

16 Case Studies Chronicling BoP Ventures : A report from the BOP Global Network By Fernando Casado Cañeque

Technology Booms in Nigeria But E-health Lags: Private sector recommended to harness opportunities By Tolu Ojo

Fundamental Funding: How basing funding on business fundamentals helps early-stage enterprises By Simmi Sareen

Framing the BoP : Dalberg’s Gupta on avoiding negative definitions for BoP business By Scott Anderson — WDI

Impact Sourcing: How combining work and study ends the cycle of poverty for good By Jennifer Liebschutz

- Categories

- Uncategorized

- Tags

- crowdfunding