What We Know – and Don’t Know – About Zika and Its Treatment

The World Health Organization (WHO) has confirmed in a scientific consensus that the Zika virus is linked with microcephaly (a condition in which babies are born with small heads and brain damage) as well as Guillain-Barre syndrome (a condition in which the immune system attacks the nerves, and weakness and tingling starts in the feet and legs, spreading to the upper body). Previously, the agency had said that there was not yet enough scientific evidence to conclude that the virus caused these conditions, although it was likely.

Since last year, the virus has infected hundreds of thousands of people in 62 countries and territories worldwide (33 in the Americas) and six countries (Argentina, Chile, France, Italy, New Zealand and the U.S.) are reporting locally acquired infections through sexual transmission. There have also been nearly 400 cases of Guillain-Barre syndrome in patients with confirmed or suspected Zika virus infection in 13 countries. A global map calculating when and where Zika virus is likely to spread shows over 2 billion people could be in the Zika zone.

According to Dr. Anne Schuchat, principal deputy director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the virus is “‘scarier than we initially thought” and could be linked to more birth defects than previously believed. Meanwhile, the Obama Administration lobbied Congress for $1.9 billion to combat the mosquito-borne virus. How might that help? How long will it take to develop a Zika vaccine and where might it come from? (I’ll get to that in a moment.)

Zika belongs to the Flaviviridae family of viruses that include human pathogens such as the mosquito-transmitted dengue virus, West Nile virus, Japanese encephalitis virus, yellow fever virus and tick-borne encephalitic virus. Zika is caused by a virus transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes. Symptoms include mild fever, skin rashes, conjunctivitis, malaise, headache, muscle and joint pain that lasts for two or more days.

There is no specific treatment or vaccine for Zika virus, and the best form of prevention is protection against mosquito bites by using insect repellents and wearing long sleeves and long pants – especially during daylight, when the mosquitoes tend to be most active. Other mosquito-borne viruses – including dengue, Japanese encephalitis and West Nile – are known to directly infect nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord. But such viruses are seldom associated with Guillain-Barre, and never with microcephaly.

A new disorder that attacks the brain and spinal cord was recently associated with Zika infections in adults: an autoimmune syndrome called acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, or ADEM. Though the study has a small sample size, it may provide evidence that the virus may have different effects on the brain. The new finding adds to the growing list of neurological damage associated with Zika.

A report published in Science announced that an image of the 3D structure of the Zika virus has been revealed. Its spherical structure is said to resemble other viruses like the dengue virus; but it also contains differences, such as the dissimilarity of its outer shell. The finding might help scientists determine how the virus is transmitted and, hopefully, how to prevent infection. The protein difference found on the virus’ outer shell could explain why Zika attacks nerve cells, for instance, and that information could lead to discovery of better tools to diagnose the disease or a vaccine.

The virus appears to have less diversity among its strains than we see for other viruses, like dengue, for example. This and the knowledge gained from dengue vaccine development should help expedite the development of a Zika vaccine. While the 3D image of the virus is an important step toward understanding the virus, several other important questions remain, like whether a fetus is more vulnerable to Zika-related birth defects at a certain stage of pregnancy.

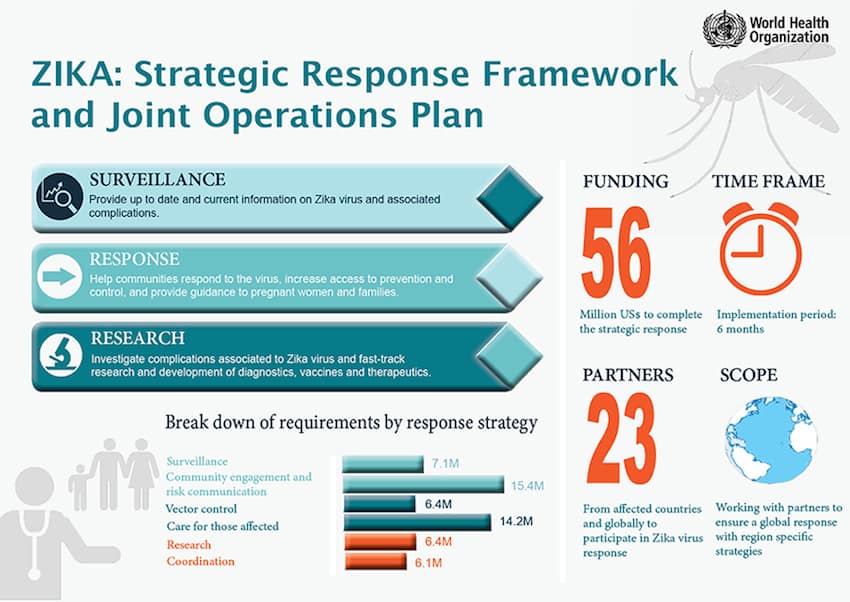

The global prevention and control strategy on Zika includes surveillance, response activities and research to better understand and characterize the virus and the outbreak. WHO launched a global Strategic Response Framework and Joint Operations Plan (infographic below) to guide the international response to the spread of Zika and the neonatal malformations and neurological conditions associated with it. WHO says $56 million is required to implement the plan, of which $25 million would fund WHO’s Regional Office for the Americas/Pan-American Health Organization response and $31 million would fund the work of key partners. This figure does not include the total cost for vaccine development – estimated to be between U.S. $200 million and $500 million per vaccine.

Until recently, Zika was labeled “non-threatening,” “rare” and “relatively benign” and there was little incentive for companies to fund research and development of a vaccine. Now, researchers all over the world have started the process. Sanofi Pasteur, manufacturer of licensed vaccines against yellow fever, Japanese encephalitis and, most recently, dengue – the same family as Zika – is currently mobilizing its experts and scientific collaborators to expedite efforts to shave years off the typical decade-long process of vaccine development. The Butantan Institute in Brazil has developed an experimental “inactivated” vaccine, based on killed, purified Zika virus. An Indian biotech company, Bharat Biotech, announced that it has two candidate vaccines ready for pre-clinical trials (before testing in humans). Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said a DNA-based vaccine is ready to go into humans, not to distribute but to test for safety and whether it induces a response that can be protective. The trial will likely start toward the end of summer or early fall. However, it will probably be next year, and possibly much longer, before we determine whether a vaccine works or not.

Until recently, Zika was labeled “non-threatening,” “rare” and “relatively benign” and there was little incentive for companies to fund research and development of a vaccine. Now, researchers all over the world have started the process. Sanofi Pasteur, manufacturer of licensed vaccines against yellow fever, Japanese encephalitis and, most recently, dengue – the same family as Zika – is currently mobilizing its experts and scientific collaborators to expedite efforts to shave years off the typical decade-long process of vaccine development. The Butantan Institute in Brazil has developed an experimental “inactivated” vaccine, based on killed, purified Zika virus. An Indian biotech company, Bharat Biotech, announced that it has two candidate vaccines ready for pre-clinical trials (before testing in humans). Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said a DNA-based vaccine is ready to go into humans, not to distribute but to test for safety and whether it induces a response that can be protective. The trial will likely start toward the end of summer or early fall. However, it will probably be next year, and possibly much longer, before we determine whether a vaccine works or not.

Some funding for research is expected to come from federal grant-making agencies and organizations such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which committed $50 million to help scale up emergency efforts to contain the Ebola outbreak in West Africa and interrupt transmission of the virus in 2014. Biotech firms and academic labs working on Zika vaccine research are expected to take full advantage of federal funding set aside for vaccine development as it becomes available.

Companies that may have solutions to emerging illnesses experience a rush in the stock market. In 2014, Ebola pushed up the stocks of many companies working on treatments. The same things is happening with Zika – Intrexon, Cerus and Inovio Pharmaceuticals are all working on methods for preventing or treating the virus and all have experienced a boost in their stock prices. While the hype and excitement from investors are understandable, it is important to keep things in perspective. Epidemic threats do not always turn into profits for developers. Take, for example, the Ebola outbreak, which was controlled before a vaccine was developed. Vaccine manufacturers are also dependent on global governments to buy their product and if you look at Ebola, the countries affected do not have the resources to purchase the vaccines.

And vaccines are not the only option in fighting Zika. A team of UK researchers has developed a strain of genetically modified male mosquitoes that can mate with females, but only produce offspring that will soon die out. The male mosquitoes have been genetically modified to require a dietary supplement that cannot be found in nature, and the gene is always passed on to their offspring. What does this mean? Less mosquitoes, less risk of transmission.

Given our current lack of understanding of Zika virus infection, clinical progression and pathogenesis, it is not certain where there is a role for therapeutic products. As our understanding of the disease progresses through research, we may discover a role in specific target groups, potentially including congenitally infected infants, long-term carriers and people with autoimmune diseases.

Moreover, assuming a vaccine will be available soon, it is currently not clear who should get the vaccine. Should it be given to pregnant women? All women of child-bearing age? Because men infected with Zika can have the virus in their semen or spread Zika through sex, should they be vaccinated as well? That’s not yet clear.

What is clear is that Rio de Janeiro will host the Olympics this August and host more than 10,000 international athletes and many more thousands to watch the games. With the increase in the number of people traveling, pathogens and their vectors can now move farther and faster than ever before, and it’s just a matter of time before Zika reaches other parts of the world.

Editor’s Note: This article was voted by readers as one of NextBillion’s Most Influential Articles of 2016.

Dr. Melvin Sanicas is a Global Health Fellow and Program Officer at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

- Categories

- Health Care