A Test Case for Digital Leap-Frogging: What the Financial Inclusion Community Can Learn from Vietnam

As one of the fastest growing economies in Asia, Vietnam represents a tantalizing opportunity for the financial services industry. But it also presents an interesting confluence of factors that could allow it to leap-frog entirely over brick-and-mortar legacy banking, propelling it to the forefront of digital financial services.

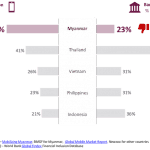

Despite astonishing economic expansion that the World Bank estimates has lifted more than 40 million people out of poverty since the 1980s, Vietnam remains largely rural (66 percent of the population) and unbanked (69 percent). There is thus no long-standing familiarity with – or loyalty to – banks, as most Vietnamese find them hard to access. This leaves the door open wider for fintechs in Vietnam than in markets where long-established banking habits would have to be broken first. In addition, Vietnam’s population is young (the median age is 30 compared to 38 in the United States), and smartphone penetration is one of the highest in the region: Among the 89 percent of rural Vietnamese who have access to a mobile phone of some sort, 68 percent of them use a smartphone. In urban areas, where 93 percent are mobile phone users, 71 percent of these users have a smartphone.

Momentum in the Sector

Just as importantly, the Vietnamese government has made both financial inclusion and digitization keys of its “Cashless 2020” economic policy framework which aims to provide bank accounts for at least 70 percent of the population aged 15 years or older and to aggressively promote non-cash payments. This will involve equipping 100 percent of supermarkets and shopping centers with point-of-sale devices to accept non-cash payment, ensuring that no less than 70 percent of utility services providers accept non-cash, and making sure that at least half of households in metropolitan areas use digital payment solutions.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given this regulatory commitment and the sheer size—64 million people—of the unbanked population, Vietnam’s fintech sector has seen significant growth and investment. In 2016, fintech accounted for 63 percent of all startup deals in Vietnam and reached USD 129 million in value, according to Topica Founder Institute research. Today there are more than 40 fintech startups in Vietnam tackling everything from peer-to-peer lending and credit scoring to blockchain technology. The payments space alone has more than 22 players.

Together with our partners at MicroSave, MetLife Foundation has been studying how digital technologies can be meaningfully leveraged to advance financial inclusion across six markets in Asia—Bangladesh, China, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal and Vietnam. Next month we will report on lessons learned at the regional level. But in the particular case of Vietnam, we have followed with interest the experience of MoMo, rapidly emerging as the leader among the 22 payment providers, for the lessons it holds about leap-frogging.

An Emerging Leader – And a Unique Strategy

MoMo is both the largest and the fastest-growing of Vietnam’s payment providers. Founded in 2014, it has 8 million customers and enjoys a growth rate of 15 percent in monthly transaction volume and user base. MoMo raised USD 28 million in 2017 from Standard Chartered and Goldman Sachs, a testament to the market’s confidence in its strategy: Alone among the 22 players jockeying for position, MoMo has adopted a dual approach of both over-the-counter (OTC) and wallet services.

Industry opinion is divided on the question of OTC, which refers to transactions in which an agent assists either the sender or the recipient, from either that person’s or the agent’s own mobile money account. One argument is that the more time users and agents both have to get accustomed to OTC, the harder it will be to ever transition to the more efficient model of independent mobile wallet account usage. However, most providers in leading markets where OTC is prevalent (such as Bangladesh and Pakistan) offer mobile wallets in tandem with OTC, just as MoMo does in Vietnam. And the counter-argument—that OTC is a necessary step along the path toward a cashless or cash-light economy—may be especially true in countries where a majority of the people have historically operated on a cash-only basis.

As MicroSave’s Graham Wright argued in an August 2016 article, in a market-led environment, service delivery should be determined by demand. For the moment, anyway, half of MoMo’s customers rely on OTC. The importance of agents—MoMo has a network of 5,000 of them across Vietnam—cannot be overstated in a context where people have not yet developed confidence in technology-based, self-initiated transactions. MoMo’s management strategy hinges on its careful selection of agents: They are primarily small business owners in rural areas, and are required to invest some of their own money, creating a sense of ownership and motivation to keep customers happy.

MoMo has made other customer-centric decisions, too, for example around the user interface of its app. Based on behavioral studies of its customers, MoMo reduced to 30 seconds—which their research suggested was the limit of the average user’s patience—the time required to install the app and register for the service. Where other interfaces can require seven to eight menu screens and input of two to three sequences of numbers just for a simple transaction, MoMo’s app has just two key steps. Its fees are affordable: less than one-third the cost of alternatives for OTC withdrawals from mobile wallet accounts. And it has agreements in place with more than 300 providers of services (e.g., utilities, mobile top-ups, travel tickets, consumer loans, insurance premiums, etc.) that cover the most common payment needs for the average Vietnamese customer. The system is integrated with international payments networks including Visa and MasterCard. And MoMo has also made significant investments in a multi-tier security system, a decision with immense practical and symbolic importance in a country whose fragile cybersecurity—Vietnam suffered more than 31,000 cyber-attacks in 2015 alone—has constrained the growth of digital financial services.

Three Suggestions for Driving Uptake

Based on our study of MoMo specifically and Vietnam generally, MetLife Foundation and MicroSave suggest three use cases which could be key to driving uptake of digital financial services—and in the process, leap-frogging the sizeable share of the population which never experienced traditional banking directly into DFS.

Domestic remittances. Although, as noted, the majority of the nation’s population remains rural, Vietnam’s economic growth has also included significant rural-to-urban migration – and with it, the classic need to send money back home to families back in rural villages. Currently an estimated 65 percent of remittances move through informal channels, a huge opportunity for fintechs supported by agents who can support cash-in/cash-out for however long it may take people to get comfortable with fully digital solutions.

Consumer finance. Demand for consumer finance is high in Vietnam: Outstanding loan balances exceed US $25 billion. Disbursements and repayments both represent a market opportunity – again especially for those fintechs which, like MoMo, can build networks of trusted agents.

e-Commerce. Approximately 70 percent of the urban Vietnamese customer segment has shopped online, and they are more likely than the global average (55 percent compared to 44 percent) to do so via their mobile phones. For the moment, most online shoppers prefer to pay cash-on-delivery given the preference to inspect the merchandise, but there is potential for partnerships and joint promotions with e-commerce merchants and logistics companies to shift consumer behavior to mobile payments, either when they place the order or when they receive the goods.

Vietnam is exciting as a test case, to be sure. Its unique convergence of rapid economic expansion, a large unbanked population, high mobile penetration and a progressive regulatory environment make it a near-perfect fintech laboratory. The interest on the part of investors like Standard Chartered and Goldman Sachs goes to show the seriousness of the sector’s promise.

For those of us in the financial inclusion community, the promise of fintech is a means to an end. What ultimately motivates us is not innovation or technology for its own sake, but rather for its potential to move millions of people who have always had to make do with informal financial services into digitally enabled alternatives that are safer, affordable, convenient — and that can better help them build the lives they want.

This article was based on a brief produced by MicroSave as part of a MetLife Foundation-funded series aimed at understanding the promise of fintech in Asia. The author gratefully acknowledges MicroSave and also Nguyen Ba Diep, executive vice chairman of MoMo, for sharing his perspectives with the MicroSave team.

Krishna Thacker is a regional director for MetLife Foundation in Asia.

Photo via Pixabay.

Editor’s Note: MetLife Foundation is a NextBillion partner.

- Categories

- Finance, Technology