Avina’s Evolution: After 16 Years, the Foundation Focuses on Building Multiple Bridges

Fundación Avina describes itself as a “broker, co-investor and facilitator” across many countries in Latin America. Indeed, the organization is often working behind the scenes, building both consensus and bridges between multinational companies, governments and microenterprises, often with the goal of bringing marginalized workers into the formal economy. It’s a strategy aimed not merely at reducing poverty in the short term, but breaking the cycle for future generations. As Avina notes in its annual report, the organization focuses on the Amazon, access to water, sustainable recycling, sustainable cities and inclusive markets, which encompasses microenterprises as well as small and medium-sized businesses. In our ongoing profiles of NextBillion Content Partners, I had the opportunity to speak with Avina CEO Sean McKaughan about the evolution of the organization and where it sees the greatest opportunities throughout Latin America.

Scott Anderson: Fundación Avina has been in operation for 16 years now. Can you tell me about the scope of the organization and how its focus may have shifted over the years?

Sean McKaughan: We’ve learned a lot and changed a lot in those 16 years. (Founder) Stephan Schmidheiny wanted Avina to be an organization that was always learning and was not afraid to change and adapt according to what it learned in order to make the maximum amount of impact with limited resources. So we’re constantly evolving. The Avina of the last two years and looking towards the future I think is an organization that has defined a lot better where it can add value. And that is, to put it simply, to help people to work together to change things. We’re not so interested in individual projects – inputs and outputs; we’re more interested in the change process. We know that complex change, the type that’s required to move toward a more sustainable development outlook, requires the collaboration of a complex web of actors: from government, from business, from the civil society sector, at all different levels. The main hurdle is getting people to work together, and getting people to have a common vision about how change needs to happen and what the roles of the players are. So that’s what we specialize in now, is brokering those types of coalitions. That’s where we put our firepower. The bigger the scale of impact you want to have, the more you have to share the work and the credit. So we don’t really do anything by ourselves, we might incubate something, but really we’re always working with a number of different partners at the local level and the international level.

Sean McKaughan: We’ve learned a lot and changed a lot in those 16 years. (Founder) Stephan Schmidheiny wanted Avina to be an organization that was always learning and was not afraid to change and adapt according to what it learned in order to make the maximum amount of impact with limited resources. So we’re constantly evolving. The Avina of the last two years and looking towards the future I think is an organization that has defined a lot better where it can add value. And that is, to put it simply, to help people to work together to change things. We’re not so interested in individual projects – inputs and outputs; we’re more interested in the change process. We know that complex change, the type that’s required to move toward a more sustainable development outlook, requires the collaboration of a complex web of actors: from government, from business, from the civil society sector, at all different levels. The main hurdle is getting people to work together, and getting people to have a common vision about how change needs to happen and what the roles of the players are. So that’s what we specialize in now, is brokering those types of coalitions. That’s where we put our firepower. The bigger the scale of impact you want to have, the more you have to share the work and the credit. So we don’t really do anything by ourselves, we might incubate something, but really we’re always working with a number of different partners at the local level and the international level.

There are two other key aspects to understand how we operate. One is we’re very opportunity driven; we look for opportunities to tip the scales in things we consider relevant for sustainable development in Latin America. We used to be more scatter shot, but we’ve really honed down on this idea of opportunity to say: is there really an opportunity to change something with what we bring to the table today?

The other element is the idea of scale. The fact that we work at a very local level with local people who know what’s going on and also that we work at the regional and even global level with a lot of players, is also a way that we can add value. Because, when we do find something that’s working or that’s making a difference, we can compare it to what’s going on in another country and see if it works there too, and then immediately start scaling that up and we can bring in other financing partners to help us do that.

We have right now eight regional initiatives, which we have scaled up in the past three or four years, things that we found were making a lot of difference locally and that there was a good chance that we could replicate in other places. For us what we call Mercados Inclusivos or inclusive markets is one of those opportunities that we’ve scaled up at a regional level. We have seven other ones, one being our work in the Amazon. We work in six of the nine different Amazon countries. We also work in the recycling industry in 12 different countries of Latin America. We work with access to water in rural areas in all 15 countries where Avina has people on the ground. We work with sustainable cities, supporting a movement of sustainable urban centers across Latin America; there are about 80 different cities that are part of that. Climate change is another area; we work in the Chaco region of South America, which is second biggest forested area in South America. We just launched a new, very big undertaking with the Ford Foundation and the Open Society Institute focused on Migration Policy in Mexico and Central America. These sorts of regional opportunities and of course inclusive markets, we see as key to the future of Latin America.

SA: And that’s obviously a critical point, reaching scale. We talk a lot about pilot projects, but we have so few success stories truly reach scale. I’m curious among those many projects you’re working on, what would you say is an example of a project that is truly scalable?

SA: And that’s obviously a critical point, reaching scale. We talk a lot about pilot projects, but we have so few success stories truly reach scale. I’m curious among those many projects you’re working on, what would you say is an example of a project that is truly scalable?

SM: Recycling is an area that has matured. We’re seeing a lot of impact and we’re working with a lot of key players all across the region. The recycling movement in Latin America is very strong. We focus on the recyclers and the cooperatives. The key learning we had there was the recycling industry in Latin America is sort of the developing country model, which is very dependent on a very exploited labor source, which is hundreds of thousands of waste pickers, as you might call them in English. These are people who go out and scavenge for aluminum cans, paper and cardboard. But basically they are the bottom of a value chain, which goes all the way to Alcoa and all the big industries, and they had been completely left out of the market. They’re exploited, they’re not recognized by the law, they don’t have access to services, they don’t have retirement, and they’re not seen as employees. So basically the way Avina approached that was to say there is an opportunity to redesign the value chain so that it generates benefits to this very important link in that chain that’s being left out. And that’s good for recycling, it’s good for the people at the bottom, and it’s good for the environment too – 80-90 percent of the cans in Brazil are recycled and I can tell you there’s no organized recycling program that does that. So we started working with that in Brazil and we realized the same phenomenon with these local cooperatives – that were struggling to be recognized within the industry – that same thing was happening in Colombia, in Argentina and Peru – everywhere we went in Latin America. And in the process, we realized this is same phenomenon is happening across India, parts of Africa, such as Lagos, etc.

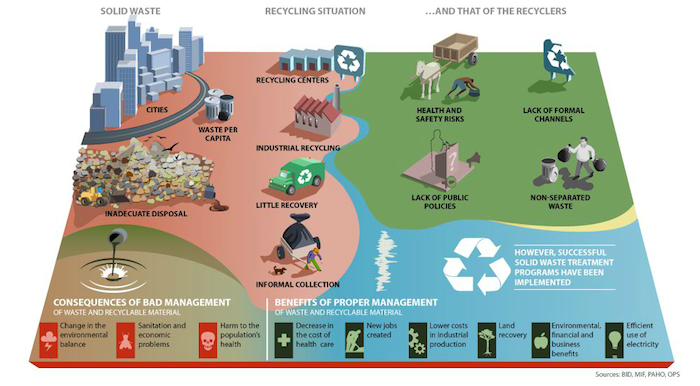

(Above: From Avina’s annual report, a look at the informal recycling sector. The graphic and additional interactive features can be found here. Image courtesy of Avina)

So we had a three pronged attack: We found ways to support the recycling cooperative movement; again not individual cooperatives, but what sort of support could they get from public policy that they weren’t getting? Who could we sit them down with in the aluminum industry, for example, so they could trade up in value chain? So we supported the movement and then we supported public policy changes that would benefit the movement, and we’ve actually seen laws change in Peru and Brazil at the national level to recognize the work of the recyclers and give them access to social benefits.

Again, Avina has contributed, but along with a bunch of other people and other organizations. We’ve also seen changes at the municipal level, where a lot cities like Buenos Aires or Curitiba in southern Brazil are now allowing recycling cooperatives to make bids for recycling contracts that the cities offer, which was not even conceivable ten years ago. It’s actually a pretty good example of inclusive business. It’s inspired us really to see within inclusive business what other sectors could be turned around like that? What other low-hanging fruit is there in front of us.

SA: In recent months, Avina has been speaking with the Cuban government, and exploring the potential of assisting the country toward developing social businesses. I’m curious if that is the next beachhead for Avina, working with countries like Cuba, those without formal market-based economies where the state is more heavily involved in enterprise?

SM: We’re really excited about Cuba, but we’re also very cautious because things are so centralized there and they have their own time horizons, and it’s not an area where we do have people on the ground yet. So it’s a little bit of looking through the window from the outside, but we’ve been very encouraged by their interest. Basically, they’re the ones who came to us and said ‘We see Avina doing all of these different activities, business social responsibility, recycling, inclusive markets, we feel it’s a good institution for us to bring into this whole experiment we’re working on.’ And being a Latin American organization, obviously that’s a good reference for them as well. Avina’s been basically bridge builder for them, whether it’s contacts in Brazil or with the business social responsibility movement, or bringing them examples of inclusive business and how they operate or providing them some experience on how cooperatives operate. And they’ve been very receptive and very interested, but we don’t really know where it’s going to go.

Looking forward, to the Rio +20 Conference, one of the main topics there is the new economy and what it’s going to look like. It’s a huge topic and I’m not sure we’re going to get a lot of clarity from a UN Conference, but I think it is one of the key questions we have right now. And it’s playing out across the globe in so many different ways right now, you can see it in Occupy Wall Street, you can see it in the European financial crisis, you can see it in the emergence of these new economies in which the government is very much involved. They are not free markets in the American sense in a lot of cases, and they certainly are not China, but even in Brazil the government is very much involved. A lot of the top companies in Brazil were once state owned or the government still has a big participation in those companies. So the question is ‘what is the economic model going to look like in 10 or 15 years?’ Nobody seems to have the answer. From our point of view, we are really excited to see that because it seemed like 10 or 15 years ago the jury had already decided what the economic model was going to be and it was an exclusive model and now people are questioning that. Climate change also brings a whole list of issues’ with it, and now things are tipping the other way so you hear ‘we know the model is broken, the question is how are we going to fix it, what is it going to look like in the future?’ So I think the area of inclusive business is going to be a big player and we want to start bringing that down to earth and giving some specific examples of what that’s going to look like. And usually when you have a new blue field area, you get a lot of diverse examples of what might be the future, just like when they opened up the Internet – there were all kinds of interpretations of what the Internet was going to look like. I think we’re in the same moment right now in these markets where there’s lots of experiments and there’s a lot of different models – state run models, or cooperative models, or slightly redesigned conventional models. We’re going to see which one of those prosper, but I think from Avina’s point of view we really need to take advantage of this opening up to different alternatives and be able to demonstrate what models we think are the best ones from a triple bottom line point of view.

SA: When you consider the progression of social business I’m curious where you see Latin America moving and how that fits into Avina’s mission?

SM: On my more optimistic days, I think Latin America is the future: it’s one of the few places that really has the opportunity to show the world what a different economy can look like. It has this wealth of natural resources. Demographically speaking it still has the demographic bonus of a young workforce. It’s got a lot of creativity, cultural diversity, innovation, and it’s increasingly feeling its oats in terms of its influence on the rest of the world. What we work for is for Latin America to become a model, where we would in this region define new way of doing things, whether you’re talking economically or politically. This model would be very applicable to other developing countries, whether in Africa or parts of Asia.

And you see this more and more. You see technology from Brazil being directly transferred to countries in Africa, or links that are increasing exponentially between China and countries in the region. There’s a lot of exchange of ideas. A country like Brazil, where I’m sitting, has one of the cleanest energy networks in the world. And it was one of the first countries that came out with its own voluntary emissions limits. It didn’t have to do that. It’s exciting to see, and it’s that kind of leadership that is the real potential of Latin America.

- Categories

- Agriculture, Environment