Digital Platforms for ‘Gig Economy’ Workers: An Intriguing Model Gains Traction in Africa

Senegal is in the process of joining the “Fourth Industrial Revolution,” in which digital technologies are transforming labor markets, creating jobs and providing governments with tools to formalize the economy. Since 2016, the country’s government has been implementing a “Digital Senegal Strategy 2025” in partnership with the World Bank and the African Development Bank. The strategy has focused on macro-level changes such as e-taxation and the digital management of ports – but there’s another area that’s in great need of digital transformation.

Only 53% of Senegalese workers received wages or were salaried in 2016, according to the International Labor Organisation’s labor force survey; that means about 47% of workers are in the informal sector. The earnings of these informal workers vary wildly, but in my survey under the Fulbright program in Dakar, they averaged less than 50,000 CFA (about US $85) per month.

In light of this situation, and considering my research outputs and my time living in Senegal, I believe that perhaps the greatest potential impact of the digital revolution in Senegal will involve helping informal workers leverage digital platforms to find work.

Misconceptions About How Migrants and Poor People Use Technology

In 2018-2019, I led a qualitative study on urbanisation, gender and work opportunities in Dakar. I interviewed both migrants and key actors in the sector about how migrants look for work, what kinds of opportunities they find, and how those opportunities differ among genders and socio-economic classes.

I went into my research project with some misconceptions about how migrants and poor people in general use technology to find work. I had assumed that in Senegal, only privileged people would use the internet to look for work – i.e.: people with high levels of education, their own computers, and intentions to work in the formal sector. But I found that people from all socio-economic classes were at least attempting to find work via digital means. Some of my research participants had dropped out after primary school, others were women looking for work cleaning houses, and men looking for work in informal trades. They were searching for opportunities on the internet via their phones, even if they did not have access to computers (the majority did not.) One 24 year-old woman who migrated to Dakar from the region of Matam told me: “Every day I try to find job postings on the internet, for myself. If I could have a position in one of the multi-service boutiques that do money transfers or even clean houses, even if it’s a salary of 50,000 francs per month [about US $85 per month or $2.75 per day] I can satisfy the needs of my child.”

The misconception that only privileged people would use the internet to find work is not uncommon. When speaking with experts and stakeholders, I encountered strong resistance to the idea that the topic was relevant. When presenting my results to an audience of international development practitioners, for example, someone questioned why I was talking about technology if my research focused on migrants from rural villages. And a representative from a local non-governmental organization vehemently told me that “technology will not fix the misery in our country.” But while there is truth to that statement, there is also a huge demand for better tech-driven tools to help workers improve their circumstances, and especially for digital platforms to help them find jobs – from e-commerce websites like Jumia or Expat-Dakar, to facilitators of “gig employment” like Task Rabbit or Lynk (neither platform is active in Senegal.)

I saw such strong usage of digital tools among my migrant interviewees, whose primary reason for migration was to seek employment, that it led me to think further: Are digital employment platforms gaining traction in other sub-Saharan African economies? If so, what do we know about them, and how could they benefit Senegal?

How Lynk Brings Accountability for Informal Workers

One example of a successful African digital job platform is Lynk, launched in 2015 in Kenya. Lynk is a website and customer-facing smartphone application that connects workers like electricians, tailors or chefs with households and businesses seeking specific services. Workers are vetted by Lynk with in-person interviews, and then they can set up user profiles detailing their qualifications. Customers use the app to search for services, and once they are connected with a worker, they book the service and make the payment up front via the platform, using a credit/debit card or mobile money (M-PESA). Both the customer and the worker rate their experience, and these ratings are published for other users to see. Once the job is finished, the money that the customer paid up front is deposited in the worker’s mobile money account within 24 hours, while Lynk retains a 10% administration fee.

A key feature that Lynk’s service introduces to workers in the informal sector or “gig economy” is a package of accountability mechanisms:

- Ratings and complaint mechanisms: With Lynk, exploitation, abuse and poor service can be reported and shared with the public through the ratings system. Serious complaints can get customers or workers banned from the site. In cases of criminal behavior, submitting a complaint with Lynk and having a record of the place and time of the crime could serve as evidence in court.

- Agreements and recorded transactions: The payment system, in which clients pay up front and the money is released to workers after the job is finished, means that workers are automatically paid on time and in full for their labor. At the same time, a record of the transaction is generated that includes the services agreed to, the contact information of the employer, the agreed upon price, and the date and time of services performed. If the contract is broken, the employer or the worker can be banned from the site.

These features directly address the key concerns of informal workers, who are usually the more vulnerable party in the cases of these transactions. These problems of accountability – refusal to pay, exploitation, the breaking of contracts and abuse – were exactly what I uncovered in my research. Nearly all of my research participants who worked informally in Dakar experienced at least one, if not all, of these issues. Many participants, particularly those working as cleaners or housekeepers, tried to protect themselves by using temp agencies that wrote up contracts for them and verified their and the employers’ identities. However, participants frequently complained that these agencies – operating largely without government regulation – were not interested in holding employers accountable. When contracts were broken or employers refused to pay, they did not take action on behalf of employees.

Informal workers are already vulnerable, since they don’t have a set and steady income. When they do get work, they need effective accountability mechanisms. Most workers I spoke to could not even benefit from a temp agency like I described above, because in Dakar such agencies are often limited to the domestic/family work sector.

So there is demand across informal workers in all sectors in Dakar for digital tools to help them find work. And importantly, Lynk’s business model has plenty of potential to generate revenue, as shown by other digital platforms in the West like TaskRabbit, AirB&B and Uber. Lynk was only established in Kenya in 2015, and since then it has seen promising growth. As of February 2019, it had processed over 22,961 jobs, and had transferred more than US $2.5 million to workers in payments on its platform, helping over 1,300 informal workers find labor.

However, investment in these kinds of digital platforms has been slower to appear in places like Senegal, partly because there is skepticism about whether there is enough demand or infrastructure to sustain them. So the question remains: Is Senegal ready for a digital platform like Lynk?

How Could a Digital Platform like Lynk Succeed in Senegal?

I believe the answer to that question is yes. Considering both my research and the government’s leadership in supporting the digital economy, much of the infrastructure necessary for a Senegalese version of Lynk is already in place:

- Broadband internet access is strong in major urban centres: Senegal’s smartphone adoption rate is among the highest in West Africa at 35.6%. Almost all of my participants in Dakar accessed the internet, and most were connected in their place of origin with mobile broadband (3G or 4G) passes on their phones. These passes are sold in small increments so poor people can afford to browse for set amounts of time.

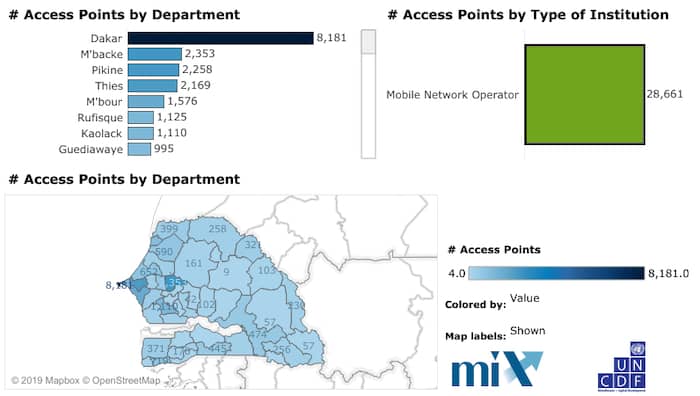

- Mobile money and strong awareness of digital financial services: Almost all of my research participants used mobile money to send remittances to their families. Mobile money is a booming sector in Senegal; it is more convenient, flexible, and adapted to the needs of poor people than traditional banking services. There is a wide range of digital finance companies in Senegal, including long-time digital payment providers like Wari and Joni-Joni; the mobile money providers Orange Money (now a market leader); Tigo Cash; and even newer entrants such as YUP, Wizall and Kash Kash. According to 2017 Global Findex data, the adult population with mobile money accounts grew from 6% in 2014 to 32% in 2017, and access points (i.e.: points where customers can cash-in and cash-out) more than doubled from 11,243 in 2015 to 30,650 in 2017.

Map of mobile money access points in Senegal as of 2017

FINclusion Lab, 2017

I believe a Senegalese version of Lynk could provide a wide range of benefits to informal low-income workers. Such a company would also create jobs in and of itself: Platforms like Lynk require a formal staff to manage the system, handle complaints and vet workers with in-person interviews, thus creating formal, full-time jobs.

As a researcher in Senegal, when I look at my own experience living and working here, and when I look at the data and trends in digital growth, I see demand and infrastructure that is already here. The government is on board, providing an environment for a digital revolution, and it is moving the economy in that direction. I believe a Senegalese version of Lynk could launch in Dakar and expand to other cities as broadband connection reaches more and more of the rural population. This is an opportunity for companies to make profits, to test and prove new business models in new markets, and to create new systems that help informal workers earn more – while providing accountability that protects employees and employers.

Note: Jessica Wallach was a Fulbright Scholar in Senegal in 2018-2019 conducting research in migration, labor and gender. Though this article was co-written with Jill Shemin, it expresses Wallach’s views and is based on her research.

Jessica Wallach is a graduate student at University of California, Davis.

Jill Lagos Shemin is a global development professional currently based in West Africa.

Photo courtesy of CTA-ACP EU.

- Categories

- Technology