From Beehive Fences to Coconut Bombs: 10 Non-Chemical Pest-Control Innovations for the Global South

Farm-raiding elephants and malarial mosquitoes count among the pests that plague the Global South. But farmers in underserved communities also contend with pests that are all too familiar on farms anywhere in the world: crop-eating locusts and harvest-munching rats and mice, for example. Finding solutions that are useful to emerging markets, however, can add constraints that are unfamiliar in the developed world. Solutions for underserved communities need to be low-cost, made from materials that are available in regions with poor distribution systems, and accessible to people who may not have much communication infrastructure or a high literacy rate.

Pest control commonly implies insecticides and herbicides, but a broader view of the term can include mechanical tools, biological pest control, digital and communications solutions and more. Here at Engineering for Change, we have listed 10 non-chemical pest-control solutions designed for farms and homes in developing countries and wherever resources are constrained. Some of these are found in our “Solutions Library” of hundreds of products that meet basic needs in underserved communities around the world, and some are found in our news pages, which include updates, analysis and opinion on technology and design that meets basic needs in the Global South and anywhere in the world where resources are constrained.

Bees vs. Elephants

A beehive fence. Photo by Lucy King

African farmers on the outskirts of protected parks are waging a battle against elephants that raid their fields at night. Little deters the animals. Elephants fill in trenches to cross them, thorny hedges barely slow them. Guns, firecrackers, spears, rocks and dogs can scare them, but those measures require sleepless nights protecting the crops. And the farmers tend to have few resources for expensive solutions such as electrified fences. Bees may be the answer. New research is finding that lines of beehives can reduce elephant raids by 80 percent compared to unprotected farms. And the effect seems universal across forest and savanna elephants and subspecies of African honeybees.

“Our studies show that farms with beehive fences experience fewer crop raids and consequently have higher productivity than those farm areas which are unprotected. Thus showing that the beehive fence is considerably more effective as a barrier than the traditional thorn-bush fences that most farmers use to keep out wildlife,” says Lucy King, who heads the Human Elephant Coexistence Program at Save the Elephants and leads the Elephants and Bees Project.

Artificially intelligent traps alert farmers of insect invasions

Louis Gerardo Holder, CEO of AgroPestAlert, displays the startup’s prototype at Orizont. Courtesy of AgroPestAlert

A new insect trap prototype in development identifies crop-eating bugs by their wing-beats to alert farmers. The Spanish startup AgroPestAlert employs a network of traps equipped with suites of sensors and placed throughout fields. The traps send their data via GSMR (2G and 3G mobile service) to the cloud, where artificially intelligent algorithms identify the species and gender with 90 percent accuracy. And the accuracy is poised to improve as the software learns through experience. The system will send alerts to phones and other screens as an easy-to-understand visual cue advising farmers about how to react.

Long-lasting insecticidal mosquito nets

An Olyset long-lasting insecticidal mosquito net.

Bed nets to keep out mosquitos are the boring-but-important item on this list. The World Health Organization has recommended nets to reduce malaria infections in children and during pregnancy. But since 2007 the guideline was updated to include everyone.

“Free mass distribution of long-lasting insecticidal nets is a powerful way to quickly and dramatically increase coverage, particularly among the poorest people,” WHO recommends.

WHO estimates 212 million cases of malaria in 2015 resulted in 429,000 deaths in 91 countries with known transmission of the disease. The incidence is dropping, however, thanks to prevention methods. There may be more exotic anti-mosquito measures on the horizon. Intellectual Ventures is working on a “photonic fence” that zaps the wings off of mosquitos with low-powered lasers, but that project has been in development for years (reportedly) and the company has not responded to requests for updates. And PATH and GlaxoSmithKline announced plans to pilot a malaria vaccine in 2018. In the meantime, the two methods that seem to work are treated nets and spraying residual pesticides indoors.

Compare these nets side-by-side in Engineering for Change’s Solutions Library: PermaNet 2.0 by Vestergaard Frandsen, Olyset Net by Sumitomo Chemical and Interceptor by BASF (sign-in needed).

Granaries, bags and fridges: Store food well to eat well

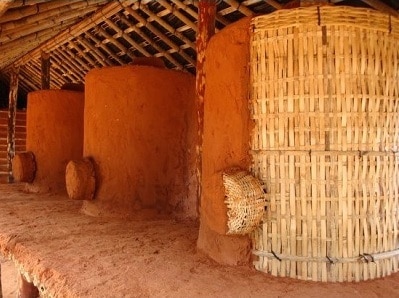

An ISSB Granary.

Post-harvest losses range from 10 to 40 percent of the rice, maize and other grains grown worldwide as they fall prey to insects, rodents and other pests. Storing food well can increase the supply and improve nutrition in the world’s poorest communities. Granaries, sacks and coolers represent three kinds of food-storage methods that are low-cost and available to people even in areas where distribution can be difficult:

Interlocking Stabilized Soil Blocks Granary (ISSB Granary), by Technology for Tomorrow Ltd.: Entrepreneurs build these granaries from earthen blocks using a block press.

Purdue Improved Cowpea Storage (PICS) bags: PICS bags keep cowpeas and other staples fresh with their high-density, hermetic polyethylene. They slow the growth of mold and mycotoxins, and control the insects that invade stored grains. Farmers using the bags can avoid the need for insecticides.

Zero Emission Fridge for Rural Africa (ZEFRA): This silo has a skeleton of woven bamboo covered with clay – materials that can be found in Mozambique, where it is distributed. Grains stored inside are further protected with herbal repellents against granary weevils and other pests. And the base contains rat and mouse traps.

Plant Village information platform for farmers

Participants in the Plant Village project in India use their phones.

The Plant Village project updates word-of-mouth wisdom to the digital age by providing a space where farmers, agricultural scientists and other experts can trade tips and learn from one another. It’s a freely available, user-moderated question-and-answer forum for people who grow their own food. The difference between this platform and others built on similar concepts is that people actually use it.

The community’s goal is to increase food security by helping farmers identify the pests and diseases that are damaging their crops. A mobile app is forthcoming, according to developers at Pennsylvania State University and EPFL.

Modular greenhouses keep pests off crops and grow with the farm

A modular greenhouse.

Greenhouses help keep insects and other pests at bay and they also promote the efficient use of water. Modular designs put these tools within financial reach for the world’s poorest farmers. Researchers in the Humanitarian Engineering and Social Entrepreneurship Program at Pennsylvania State University are customizing their modular greenhouse designs to adapt them to the climatic and agricultural conditions in different regions.

This field report offers a look at that process of design adaptation: “The Redesign of a Modular Greenhouse in Mozambique.”

Coconut bombs fight Zika, malaria and dengue in Peruvian villages

Researchers and residents of Salitral toss coconuts innoculated with Bti into ponds around the village. Photo courtesy of Palmira Ventosilla

Bacteria-breeding coconuts can control mosquitoes that transmit Zika, malaria, dengue and other diseases, researchers in Peru have discovered. The bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis israelensis, or Bti for short, lives in soil and on plants and insects. It produces a toxin that kills dozens of species of mosquitoes, blackflies and gnats, but has little to no effect on other insects, fish, birds or mammals.

Palmira Ventosilla, a microbiologist at the Experimental Microbiology Lab at the Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia in Lima, Peru, developed a homegrown method for incubating the mosquito killer. It turns out that Bti thrives and multiplies inside a coconut. Ventosilla and her team tested coconut incubators in jungle villages. They recruited students to inoculate coconuts with Bti, store them for incubation and then toss the coconut bacteria bombs into ponds around the villages.

“We can control 72 species of mosquitoes and blackflies with this method, including Aedes aegypti, a vector of Zika, dengue, yellow fever and chikungunya,” Ventosilla says.

Crowdsourced malaria control with Humanitarian Open Street Maps

A Humanitarian Open Street Map team.

Humanitarian Open Street Maps has paired its worldwide volunteer network of map updaters with DigitalGlobe’s satellite imagery to help fight malaria. Volunteers update the open-source maps to pinpoint the places where mosquitoes thrive in Africa, Southeast Asia and Central America. The improved maps guide insecticide sprayers working with the Clinton Health Access Initiative. Anyone can take part; follow the link for details.

A “solar hooter” protects southern Indian farms from animal raids

A “solar hooter.”

A low-cost “solar hooter” may keep animal intruders at bay on southern Indian farms. The device flashes a light and emits a loud sound periodically to scare off nighttime invaders. Monkeys, rats, birds and other animals raid farmers’ fields to eat their crops. Student engineers at the Indur Institute of Engineering and Technology in Siddepet, in the state of Telangana, have developed the hooter as a cost-effective solution. The raw materials total 3,000 Rupees (about US $50), but the device is not yet available for retail sale.

Ethiopia’s 8028 Hotline aids farmers by text and interactive voice messages

An Ethiopian farmer with his phone. Courtesy of Bioversity International/J.van de Gevel

Ethiopia’s 8028 Hotline for farm information launched in 2014 and it has already handled 17 million calls from 2.2 million registered users, amounting to more than 2 percent of the country’s entire population. Farmers can text the hotline for answers and it broadcasts updates by text message (SMS). It also caters to illiterate users with a call-in voice response system. And information is provided in Ethiopia’s three major local languages, Amharic, Tigrigna and Oromiffa.

The hotline shares information about the full value chains of 17 crops, from pre-planting to post harvest. Topics range from crop disease to the best agricultural practices to equip farmers with the tools needed to make timely decisions. With help from the hotline, farmers can identify the signs of disease and control it as early as possible, before it reaches the point where chemicals are needed or crops are lost.

E4C’s Solutions Library

Some of the technologies in this list are also featured in Engineering for Change’s Solutions Library. The library is free and allows for side-by-side comparisons of similar products. There has been an explosion of products and services that meet basic needs in underserved communities in the past decade, but information about them is uneven and limited to what each purveyor provides. Engineering for Change has worked to standardize the data on each product in its library. The goal is to make comparison easier and also to encourage designers and manufacturers to provide specifications for their products, field test data and other useful information.

Rob Goodier is the managing editor at Engineering for Change and a freelance journalist.

Top photo: Lucy King stands along a line of top-bar beehives protecting a farm in Kenya. Courtesy of the Elephants and Bees Project

Homepage photo: Sakke Wiik, via Flickr.

- Categories

- Agriculture, Social Enterprise, Technology