Gender: The Blind Spot of the COVID-19 Response in Low- and Middle-Income Countries

The COVID-19 pandemic has posed unprecedented challenges for governments and citizens around the world, straining health systems, economies and the very social fabric of nations. The risk associated with this crisis is especially high for those with limited access to resources due to their gender, geography, age and ethnicity.

Women comprise an overwhelming majority in this segment. Emerging evidence suggests that the pandemic is imposing a disproportionately higher socio-economic cost on women. As Melinda Gates, gender equality advocate and co-chair of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation put it, “COVID-19 is gender-blind, but not gender-neutral.” In this article, we discuss four potential types of fallout from COVID-19 that will have lasting socio-economic impacts on women in India and other low- and middle-income countries. These are based on multiple studies that MSC conducted between March and July of 2020.

Potential fallout #1: Women are more economically disadvantaged

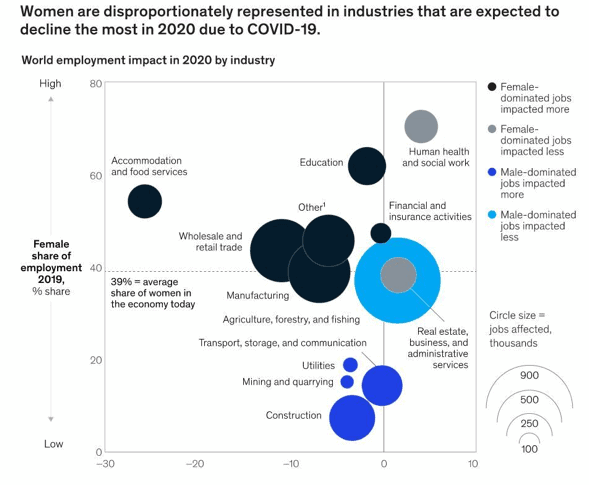

A research note from Citigroup estimates that of the 44 million workers in vulnerable sectors across the globe, 31 million women face potential job cuts, as compared to 13 million men. McKinsey reports that women’s jobs are more vulnerable to this crisis, with the job loss rate for women 1.8 times higher than that of men. Women make up 39% of global employment but account for 54% of overall job losses.

This disproportionate loss of women’s jobs seems to be a worldwide phenomenon. In Britain, mothers are 1.5 times as likely as fathers to have lost or quit their jobs during the lockdown. In the U.S., women accounted for 55% of job losses in April of this year, despite making up less than half of the workforce. This disparity is partly because women are overrepresented in sectors that the crisis has acutely affected, such as hospitality and tourism.

Even before the pandemic, more women than men in India were unemployed. The pandemic has only worsened this situation. MSC’s studies across Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Kenya and Uganda find that women tend to be more worried about the lack of employment, food shortages and the financial crisis. These differences are particularly acute in India and Uganda. (For more details, please refer to this country-level comparison dashboard).

MSC’s recent research on the impact of the crisis on the low- and middle-income (LMI) segment and micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) confirms that COVID-19 is widening the pre-existing socio-economic gender gap. In India, as many as 82% of women-owned MSMEs reported a decrease in their income, as compared to 72% of male-owned enterprises. Women-owned MSMEs face greater restrictions, decreasing demand, rising costs of inputs, inability to access markets and an increased burden of care work at home, among other factors that severely affect their incomes.

In addition, according to the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report 2017, on average, 66% of women’s work in India is unpaid, compared to just 12% of men’s work. Mounting job losses and the economic slowdown will likely raise the household debt delinquency ratio and increase the proportion of women in unpaid work. MSC’s research on the LMI segments confirms that the burden of unpaid work has increased for women by 54% in Asia and 12% in Africa.

Potential fallout #2: COVID-19 will further restrict women’s mobility and increase the information gap on addressing health-related vulnerabilities

Through our studies focused on the LMI segment in Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Kenya and Uganda, MSC has identified TV and radio as the main sources of information on COVID-19 for both men and women. However, women rely more on their social networks to obtain information on COVID-19, such as neighbors, local shops, friends, relatives and local government extension workers. Only 25% of men rely on their social networks to procure information, as compared to 40% of women.

The pandemic has also further limited women’s mobility, due to the lockdowns announced to curb its spread, limited or no availability of public transport, and stringent social distancing measures. This severely affects not only the lives of individual women, but also the functioning of women’s collectives like self-help and joint liability groups. These groups are now unable to hold physical meetings and interactions, which limits women’s access to support systems and networks of information outside their homes.

Potential fallout #3: COVID-19 will suppress women’s voices and rights

Countries across the globe have reported an uptick in intimate partner violence associated with the lockdown. This is alarming, especially in light of data from the National Family Health Survey 2016 that suggests one in three women experience intimate partner violence in their lifetimes. A working paper published by the U.S. National Bureau of Economic Research compiled complaints registered with India’s National Commission for Women. It found an increase in the number of domestic violence complaints in red zone districts — those with strict restrictions on mobility. The average number of monthly complaints in these districts increased from below 1.5 before the lockdown in March to almost two during the lockdown in May. A recent MSC study in India that is yet to be published finds that 13% of respondents noticed an increase in incidences of domestic violence in their neighborhoods during the lockdown.

Meanwhile, on the global level, the United Nations Population Fund warns that the pandemic could undo almost a third of the progress made against gender-based violence.

Potential fallout #4: Women will be left behind in the race for digital adoption

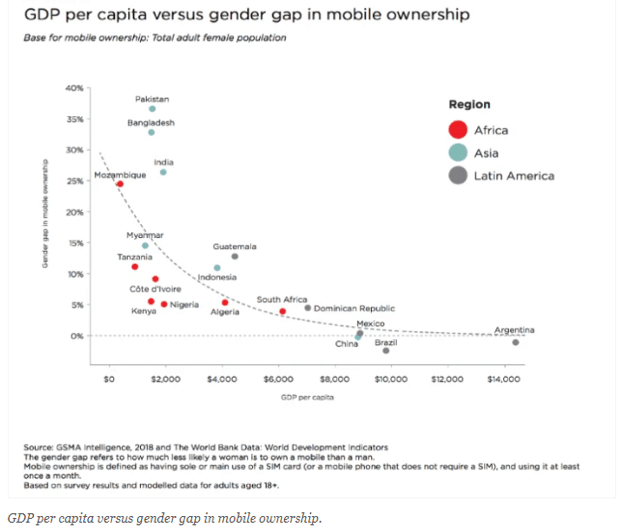

Women generally lose out on access to and adoption of technology, given the persistent digital gender gap. GSMA reports that women in low- and middle-income countries are 8% less likely than men to own a mobile phone and 20% less likely to use mobile internet. A recent multi-country LMI study by MSC finds that across Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Kenya and Uganda, only 56% of women have smartphones, compared to 70% of men. The gender gap in mobile ownership is particularly large in Bangladesh, India and Uganda. Growing evidence suggests that, for the short-term at least, global smartphone sales are plummeting. The MSC report also points to women’s increased reliance on cash in the current situation. It shows a gender gap in the time spent on phones for any activity, implying reduced scope for women to adopt digital financial services. It also finds that 22% of men in these countries have increased their use of digital payment applications, compared to 15% of women.

MSC’s previous research with garment factory workers in India found extremely low adoption of digital channels among women. Though 36% of female workers have a smartphone, just 3% of them use mobile banking services, compared to 22% of male workers. The trend is similar among other channels, such as mobile wallets and BHIM, India’s mobile payment application. The absence of a strong digital ecosystem is another factor behind this low uptake, as digital channels and products are not designed around the needs of women in this segment.

Several factors already work against women when it comes to the adoption of digital channels. These include reduced mobility, limited or no access to and control of phones, and a relative lack of their own money to use during the transaction Additional obstacles include the absence of a strong digital ecosystem, a lack of women-focused products in the market – and more importantly, the fear of losing money in case of a failed transaction. Given these challenges, the prevailing gap in digital adoption may either remain unaltered or grow further during the pandemic.

The signs of this widening gap are already present. MSC’s research with Indian MSMEs highlights that 33% of enterprises have started using social media for communication, while 10% have partnered with e-commerce players to mitigate risks to their businesses. However, these strategies were mainly confined to urban men. The research also indicates that India’s digital divide will further widen the education gap.

In conclusion, a gendered approach to planning for post-crisis recovery and reconstruction will help mitigate the larger-scale consequences of COVID-19 for girls and young women. If women’s unique needs and challenges are neglected, it may lead to greater gender disparity. Practitioners and policymakers both face an important test, as their actions will determine whether women are left behind in the post-COVID-19 world or not. The United Nations Secretary-General, Antonio Guterres has rightly called for the inclusion of women’s needs as part of the strategic response to COVID-19. Policymakers around the world are now responsible for crafting gender-responsive actions, and establishing gender justice and equality as a more prominent part of the mainstream pandemic response. The awareness of gender issues and the prioritization of gender rights and interests can not only get us through this pandemic faster, it can also help us move toward building an equal, inclusive and resilient society after the crisis has passed.

Note: This article includes inputs from Akhand Tiwari and Parul Tandon.

Aakash Mehrotra is a manager at MicroSave (MSC) India; Rahul Chatterjee is a manager at MicroSave; Saloni Tandon is a manager at MicroSave’s Inclusive Finance and Banking domain; and Sonal Jaitly is a Senior Manager at MicroSave’s BFSI Domain. MicroSave (MSC) is a NextBillion partner.

Photo courtesy of kabita Darlami.

- Categories

- Coronavirus, Finance, Technology