How to Help Low-Income People Save for Retirement: Make it Personal

The U.S. Social Security system is in a dire state. The latest report from the Social Security Administration projects that its trust fund will be completely depleted by 2034, which means that many Americans may not be able to rely on state funds to support them during retirement in the near future. This makes saving for one’s own retirement particularly crucial in the U.S. – and it’s certainly not the only country where voluntary savings are needed to ensure a comfortable retirement. In many developing countries, too, solvency issues have forced governments to replace or supplement defined benefit systems with defined contribution systems that allow members to contribute directly to individual long-term savings accounts.

Because a defined contribution system allows each member to save for herself, it is not prone to the same risk of bankruptcy as a defined benefit system, which essentially transfers the contributions of current workers to current retirees. However, because an individual’s payout in a defined contribution system depends on the amount he contributes before retirement and the returns earned on the contributions, it presents its own challenges. Saving is difficult, particularly for individuals with lower incomes; pressing demands are always present and the benefits are never immediate. This is particularly the case for pension savings, where the fruits of one’s current sacrifices may only be visible in 30 or 40 years. In addition, defined contribution systems require a better understanding of the financial system than defined benefit systems: while day-to-day investment decisions about members’ accounts are generally taken by an investment firm, members must make choices about how risky their investment portfolio should be or the appropriate amount and frequency of contributions. Unfortunately, most surveys show that individuals have limited knowledge and capacity to understand such complex decisions.

In Chile, the Superintendencia de Pensiones (SP) supervises the defined contribution system and has implemented a series of initiatives that aim to improve the likelihood of a comfortable retirement for Chileans. Since 2005, the SP has been sending personalized pension projections to individual contributors, and in 2012 the institution implemented a web-based pension simulator that gives users a measure of pension risk (indicating for example the likelihood of different scenarios for their retirement income). However, until now there hasn’t been an initiative that specifically targets lower-income individuals, who are more likely to lack financial knowledge and less likely to save consistently, both of which may in turn lead to a lower pension payout.

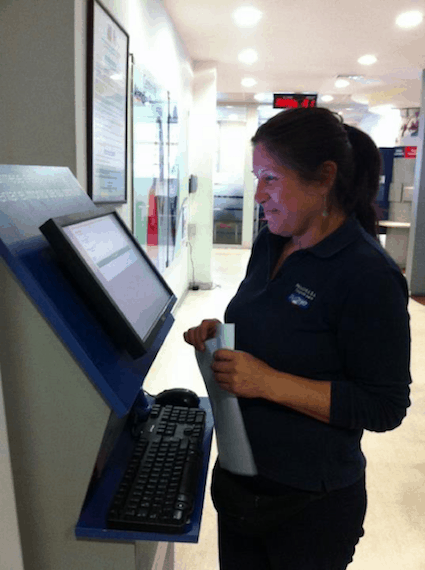

A Chilean woman uses a computerized retirement module to check her pension payout. Photo credit: J-PAL LAC

Can personalized information about their pension payouts help these lower-income individuals achieve a more decent pension? To find out, we, with support from the Citi IPA Financial Capability Research Fund at Innovations for Poverty Action (a NextBillion content partner), worked with the SP in Chile to measure the impact of providing personalized information on the savings behavior of low-income people using a randomized controlled trial, or RCT. We chose eight government offices that tend to experience a high degree of foot traffic from the public. In each, we placed a computer that was connected to the SP’s database containing information about retirement savings, with both accumulated savings and past contributions, and the pension simulator they created in 2012. Any members of the public who walked into the government offices were welcome to use a retirement module that ran on the computers.

The module emphasized to all participants the need for retirement savings, and mentioned the three main mechanisms that can increase savings: increasing the number of mandatory contributions made in the year, making voluntary contributions, and delaying retirement age. To understand whether personalizing the information that individuals saw affected their behavior, we randomly selected half the users for an additional experience. For these users, the SP’s simulator used information from the database (including the user’s pattern of contributions, retirement age, formal employment status and more) to compute an estimate (in Chilean pesos) of their eventual pension payout, and how decisions about the three main mechanisms would impact that payout. This personalized information was presented to the users as part of the module. Given the complex nature of the decision process, it was our hypothesis that receiving simple, personalized information may enable low-income individuals to make healthy decisions about their pension savings.

The Results

So far we have followed individuals’ savings for the eight months following their use of the module. We find that individuals who received personalized information were more likely to have made voluntary contributions to the pension fund system after their visit and that the amounts were larger. The effect has persisted for all eight months, showing no sign of fading over that time frame. Although the increases are small in absolute numbers, the effects are substantial when compared to the initially low contribution rates and amounts: they correspond to an increase of 30 percent in the number of individuals making contributions, and an increase of about 15 percent in the amounts contributed. (It should be noted, however, that even after the personalized information intervention a large majority of the participants still do not make voluntary contributions). We do not see any difference in mandatory contributions, which are linked to formal employment status by definition. That may be because changing formal employment status requires one to have the opportunity to obtain a formal job or to expand the current number of months with a formal, albeit transitory, contract.

We can only measure the savings within the pension system, but based on our phone surveys, the personalized information generated an increase in overall savings — participants did not report moving existing savings from other savings account into their pensions. We also found that providing personalized information improved the view that individuals have of the system.

Who was particularly responsive to the personalized information? We find that women and younger individuals responded more strongly by increasing their voluntary contributions. This may be because they are the ones who can gain most from these limited changes, because young people still have many years for their savings to grow and women have lower labor force attachment, making voluntary contributions more important.

We also see that people who received “bad news” about their pension savings – in other words, those who believed that their pension payout would be higher than what the simulator stated – saved more.

Finally, we also observe that personalized information led some individuals to retire more quickly than they would have if they had only received the generalized information. This effect is concentrated among individuals at or past retirement age, suggesting that personalized information may discourage individuals from working if they are of an age at which extra savings may not do much for tomorrow’s pension. This is important as a cautionary tale for policy makers: providing personalized information appears to be highly effective as a way to increase pension savings in our context, but for some individuals, the information may lead to some undesirable responses.

The world is getting older: Globally, the number of older people (aged 60 years or over) is expected to more than double, from 841 million people in 2013 to more than 2 billion in 2050. It is thus crucial that we think about how this growing fraction of the population will be able to provide for themselves. Many private pension fund providers around the world are trying to encourage clients to consider their pension savings by providing them with a prediction or projection of their pension payout; our results validate this approach and suggest that the more personalized this type of information can be, the larger the impact it can have.

It’s important to keep in mind that our results also illustrate that this policy alone will not induce the type of changes required for everyone to acquire adequate savings for retirement. But given that we didn’t use any additional behavioral mechanisms or incentives to encourage saving in our study, these impacts may be the minimum that can be achieved when personalized information about pension savings is provided to consumers.

Note: This study was supported by the Citi IPA Financial Capability Research Fund, a fund within IPA’s Financial Inclusion Program which supports research on innovative products and programs that aim to improve the financial capability of low-income people in developing countries.

Main photo: A woman in a market in Santiago, Chile. Credit: Francisco Osorio via Flickr.

Olga Fuentes is deputy chair of regulation at the Superintendencia de Pensiones in Chile. Jeanne Lafortune is an associate professor at the Economics Department of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. Julio Riutort is an assistant professor at Adolfo Ibáñez University. José Tessada is an associate professor at the Business School of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. Félix Villatoro is an assistant professor at Adolfo Ibáñez University.

- Categories

- Investing