Avoiding the Downside of Instapay: Five Behavioral Science-Based Principles to Make Paycheck-on-Demand Benefit Low-Income Users

You just finished an hour of work. You glance at your phone and there is a notification that you got paid. Money is in your bank account – free for you to spend immediately. In the past, you’d have to finish days and weeks of work, then wait for your paycheck to hit your account, before you could cash in on your labor.

There are now numerous apps you can manually attach to your paycheck that cash you out immediately, rather than waiting until your weekly or bi-weekly payday. There are employers (like Walmart and Uber) that are making it seamless to do. And, fearful of being left behind, payroll providers are now offering ways to turn a monthly paycheck into an instant paycheck.

This may seem like a dream come true for many employees who need to pay their bills a day before their paycheck comes in. And in a time of COVID-19 and shelter-in-place guidelines that are forcing people to squeeze more out of each paycheck, the need – and the temptation – to cash out early is even greater. Nearly half of U.S. households have had their incomes decline during the pandemic, and “instapay” allows people to tap their funds to help pay bills and make rent while under financial distress. However, instant access also comes with tradeoffs, and it carries a hefty burden that hasn’t yet made headlines.

The Surprising Downside of Instant Paychecks

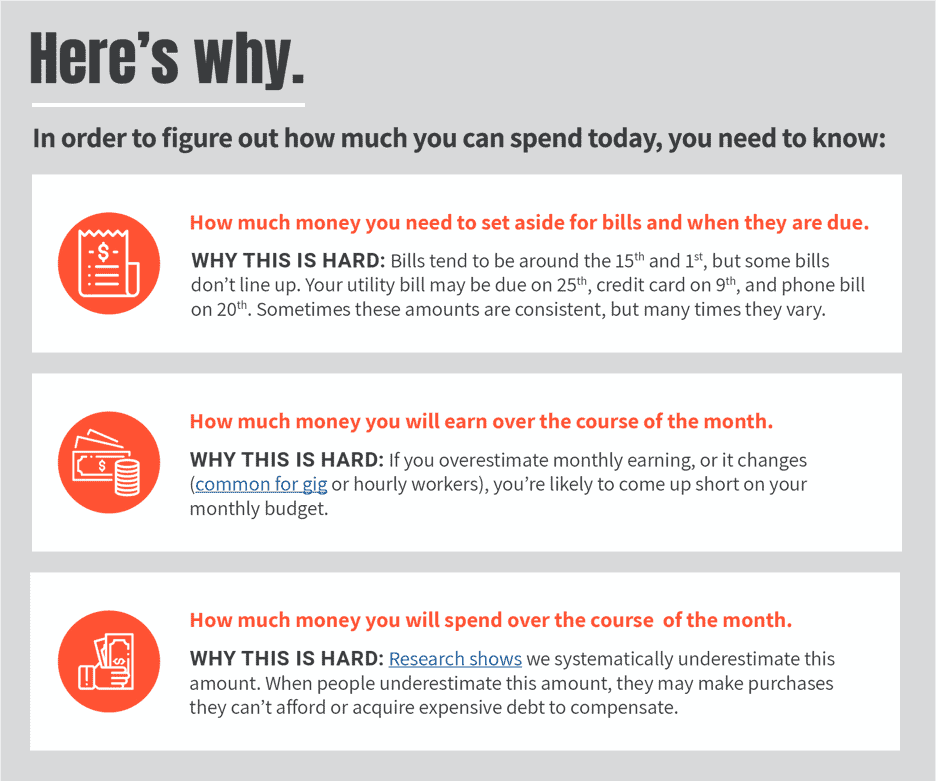

People are currently dealing with financial scarcity in record numbers, which makes it more difficult for them to perform the tough calculations required to conduct effective budgeting. Weighing whether it’s possible to order takeout tonight versus setting aside extra money to pay rent in three weeks forces us to consider immediate benefits versus future ones. It’s the equivalent of asking people to avoid eating a cookie when they are really hungry. Sure, it’s possible, but it’s really hard. The following graphic explains why:

Only when you know these three things can you decide if you can afford to splurge on ordering in or purchasing family entertainment online. This is an advanced math problem that requires a predictive algorithm. It would be difficult for anyone. But it’s even harder for people living paycheck to paycheck, because financial scarcity tunnels their thinking to the present moment and inhibits their ability to plan for the future.

How do people manage this equation now? They don’t. They rely on the paycheck to make budgeting simple. For example, if people get paid twice a month, they might use their first paycheck to pay a car payment and a second paycheck to pay rent. If people use flexible pay to cash out their incomes regularly, it can become harder to come up with larger sums of money to cover rent and car payments.

The future world of instant paychecks that we envision takes away one of people’s most effective budgeting hacks, and leaves them with a math problem.

At Common Cents Lab, we use behavioral science to develop and test products designed to improve the lives of low- and moderate- income Americans. In our experience working with companies developing flexible pay alternatives, we’ve observed how this complex math problem plays out. Based on our work, we have come up with five behaviorally-informed design principles that all employers and payroll providers should consider before rolling out a flexible pay (instapay) solution.

Help Avoid the ‘More Paydays = More Spending’ Pitfall

In response to the pandemic, people are cutting back on discretionary expenses, with real consumer spending down by 11.2% below pre-pandemic levels as leisure, auto and recreation spending all having dipped.

Instapay may make this reduction in spending harder to do. Research from Arna Olafsson and Michaela Pagel finds that both poor and rich households spend more on payday, with the poorest households spending 70% more on discretionary expenses on the day when they get paid than they would on an average day. Flexible pay gives us more paydays in which we suddenly have more money, feel richer and are more willing to spend.

Given this research, we expect that flexible pay will encourage more spending. To help people make these decisions, both during the pandemic and as a new normal emerges, we recommend framing flexible pay as a short-term cash advance or zero interest loan. This helps signal that people should use flexible pay when there is a gap between income and expenses.

Flexible pay should not be used on everyday expenses like groceries or clothes. We recommend instapay providers give concrete recommendations on when to use the service. For example, people should use it for a flat tire or an unexpected bill – the kinds of unanticipated expenses that might normally force them to seek a payday loan. This mental model of infrequent usage is financially beneficial to users because it helps people avoid the trap of spending more when they get paid.

Ask People to Pre-Commit When They Want to Cash Out Early

If a plate of cookies is set out in front of us, most of us will likely eat at least one. Failures in self-control are a universal issue and should not only be expected, but planned for. And there are ways to mitigate our lack of self-control: If we move the cookies farther away or cover them up, we will eat less. Money is a bit like cookies. When money hits our bank account, we are tempted to spend it.

That’s why we recommend that providers who use flexible pay ask people to decide in advance when they want to allow themselves to cash out. This is called pre-commitment, and it’s a proven tactic that ensures our intentions match our actions. By reminding people of their pre-commitment at the point of temptation, we can help them act in their own best interest.

Build in Accountability Checks Prior to Cash-Outs

Our actions often diverge from our best intentions when no one is watching. If nobody knows about it, you may feel free to stay up late watching Netflix and eating pizza. However, when someone does know what you’re up to, you may think twice. You may not eat as much pizza or stay up as late. Accountability refers to the expectation that one may be called on to justify one’s beliefs, feelings and actions to others. Accountability has been shown to increase voter turn-out, graduation rates for students, handwashing in hospitals, charitable giving and more. It works when our actions are visible to others, or when we know we may have to justify our actions to others.

To ensure that cash-outs improve well-being, we can allow flexible pay users to build accountability into the system. Imagine if users could add an accountability buddy (a spouse, parent, etc.) who would be emailed, called or texted with the amount and reason for cashing out. People could opt in, knowing this could help them manage their money in a way that better represents their intentions. Voluntary accountability systems are frequently used within dieting, exercise and saving groups.

Combat Unintentionally Large Cash-Outs with Anchoring and Smart Design

“It’s my money. Why shouldn’t I take everything out at once so I can have full access to it?” This is how some media have introduced the benefits of flexible pay. But this comes at a cost. Flexible pay providers deduct what people take out today from their upcoming paycheck. This means the more people take out today, the less they have on payday. This removes the ability for the paycheck to act as a savings mechanism.

To mitigate this, we recommend two things. First, ask people what they need to take out, before sharing the maximum totals they are allowed to take. You may be allowed to take up to $500, but you only need $239. If you see the $500 limit first, it will be tempting to take it all out.

Second, people consistently round up payments to amounts that are cognitively easier to process and remember. If you use flexible pay for a bill of $162 then you might round up a cash-out to $200, just to be safe, leaving the additional $38 to burn a hole in your pocket. To mitigate this, any round number inputted for cash-out can be met with an error message, prompting users to think about and insert the EXACT amount of money they need for a specific purpose.

Set Guardrails

If flexible pay allows people to take out a lot of money in between paychecks, people will be left with pennies on actual payday. After receiving a low paycheck, what is likely to happen? The person will use flexible pay to take more money as soon as possible, reducing their next paycheck. Thus, a cycle begins. Once we’ve established a habit, the habit can be very difficult to break, both psychologically and financially. So people might find that their finances are reliant upon their ability to cash out early, akin to a payday debt cycle.

This is a tough nut to crack. But there are a few ways flexible pay providers can help. We suggest creating guardrails. First, limit the number of cash-outs, ideally to no more than two per month, in addition to regularly scheduled paychecks. In this model, people will be able to get paid every week while avoiding the “every day is payday” mentality and the trap of cyclical cash-outs.

Our second recommendation is to proactively help people get out of the cash-out cycle faster. Providers can ask people if they want to “round down” their paycheck at the point of flexible pay withdrawal (e.g.: reducing it from $382 to $350) and put the extra money into a savings account that they can easily access. By setting aside money from the paycheck for later, people will get back to a “whole” paycheck quicker and be less likely to fall into an early cash-out cycle.

Flexible pay options can help workers manage their cash flow by bridging the gap between income and expenses. However, the practice may backfire. If done without these five principles in mind, flexible pay may come at a cost to a worker’s long-term financial health. We hope providers design with these five behaviorally-informed principles in mind to make this innovation beneficial for everyone.

Richard Mathera is a behavioral scientist, and Kristen Berman and Mariel Beasley are co-founders, at Duke University’s Common Cents Lab.

Photo courtesy of Michael Longmire.

- Categories

- Coronavirus, Finance, Technology