The Jobtech Landscape in Africa: Assessing the Challenges and Opportunities in a Critical Sector

What really is the future of work in Africa? Though it’s difficult to make confident predictions about such a dynamic and rapidly changing region, Africa is beginning to feel the impact of the same trends that are reshaping labour markets in more developed countries. For instance, if we look at the evolution of labour markets in Western countries over the last decade, the biggest shift has been in the way people find and mediate their work: They increasingly find jobs through job matching platforms, manage their businesses through e-commerce platforms, and earn money on the side through gig matching platforms. These digital platforms are part of a broader effort to use technology to enable, facilitate or improve people’s work opportunities, productivity and livelihoods — an emerging sector that’s collectively known as “jobtech.”

While not yet as ubiquitous in Africa as it is in Western markets, the shift toward jobtech is coming to the continent. Simply put, jobtech is the future of work in Africa: Up to 540 million people worldwide will benefit from online talent platforms by 2025, and significant growth of the e-commerce sector is expected in Africa, with 30-88 million Africans expected to earn income from digital marketplaces by 2030. The Briter Intelligence database counts 1,007 jobtech platforms in Africa today.

As we’ve seen in other markets around the world, jobtech has the potential to create new work opportunities that were not previously possible, improve the regularity and quality of work, increase the size of income, and overcome traditional barriers to access for marginalised groups. But these countries have also shown that it can generate bad work as well as good, and create new barriers to access for these same marginalised groups.

As the shift toward jobtech accelerates in Africa, it will be important to keep these potential downsides in mind, since the continent has uniquely challenging market fundamentals, and there is a lack of innovation in the broader employment space. For instance, jobtech workers’ participation in formal employment platforms subjects them to regulations around minimum wage, taxation, work conditions, etc. — yet they must often compete with workers in the informal sector, who earn (often illegally) low wages, and who are faced with non-existent or ambiguous requirements around taxation and other labour norms. Moreover, weak domestic demand for labour isn’t fundamentally fixed by layering tech-enabled matching — much more is needed to create work, or (in the language of Efosa Ojomo and Clayton Christensen), to move non-consumption of labour into consumption of it. These market fundamentals make it difficult for platforms to achieve viable business models, and for those platforms to offer quality work to their users.

However, compared to thriving ecosystems like those of fintech and edtech, where entrepreneurs learn and collaborate through meetups, WhatsApp groups, blogs and events, the jobtech ecosystem is extremely nascent. None of these resources have historically existed, and even the term “jobtech” has only come into common usage in the last couple of years, as a shared language around the sector has gradually started to emerge. This lack of visibility, shared knowledge, community and collaboration limits the scope of the innovation that is desperately needed to drive the sector forward. Yet even with these issues, jobtech has emerged as a diverse and evolving sector in Africa, with huge potential to alleviate its youth unemployment challenge by meeting the current and future need for millions of jobs across the region.

Segmenting the Jobtech Landscape in Africa

Given this potential, and the fact that the sector is so nascent, it is important to define the continent’s jobtech landscape. To that end, the Jobtech Alliance — an ecosystem-building initiative steered by Mercy Corps and BFA Global — aims to advance inclusive jobtech in Africa by developing a taxonomy that segments the sector into five categories. These categories include:

- Platforms for offline work — i.e., platforms where the work is mediated online but delivered offline. Most people first think of ride-hailing apps like Uber or Bolt when considering this category, but it also includes other types of platforms, from job boards and other recruitment platforms to distributed manufacturing.

- Platforms for digitally-delivered work — i.e., platforms where the work is both mediated and delivered online. This category ranges from the more traditional types of digital work, like skilled online freelancing, managed services/business process outsourcing and microwork, to platforms like YouTube that enable creators to monetise their work. There’s even an emerging field of (often blockchain-based) platforms enabling people to earn money or tokens through learning, playing, trading and more (these platforms are often called “X-to-earn”).

- Digital services for microenterprises — i.e., platforms that improve the market access, business performance or productivity of self-employed individuals or microenterprises. These include e-commerce marketplaces like Jumia, social commerce/digitally-enabled agent networks such as Moniepoint, and business management tools.

- Tech-enabled skilling — i.e., edtech platforms that equip people for the future of work. This skill development can be guided or self-paced, and these platforms may also facilitate access to networking/information and other tech-enabled opportunities (e.g., internships).

- Tools for worker enablement — i.e., nascent digital platforms that provide workers with tools that enhance their rights, benefits and protections. These typically build on top of the above categories of jobtech, or use the data from platform work — and they could include things like portable benefits or digitised collective action.

Critical to the success of an ecosystem is a shared language and understanding of the sector itself. But the sector we now call “jobtech” has historically used fragmented and overlapping language to talk about different elements of the space — e.g., “digital jobs,” “gigmatching,” “platform livelihoods,” “future of work,” “e-commerce,” and much more. This patchwork of terminology lacks the relevance, intuitiveness — and quite frankly, the sexiness — of the more cohesive language used in sectors like fintech. The above taxonomy aims to start to provide a shared language for the various stakeholders — startup entrepreneurs, investors, philanthropic donors, accelerators and researchers — operating in this wide-reaching and critical sector.

Current Trends in Africa’s Jobtech Sector

Building on BFA Global’s experience working with hundreds of jobtech startups in Africa over the last few years, and the acceleration work we’re doing with over a dozen African jobtech startups through the Jobtech Alliance, we recently launched the sector’s first ever Landscape Scans. These reports are focused on identifying common business models, key players, trends and business opportunities across the jobtech industry.

Looking across the Landscape Scans, a few common trends are visible: First, while the initial wave of jobtech in Africa replicated Western models, these have typically struggled to achieve viability and scale on the continent (see Landscape Scan I – Platforms for Offline Work). While white collar job-matching platforms in Africa have helped to improve transparency and address labour market efficiencies, they haven’t been able to make up for the fundamental lack of formal sector jobs on the continent. On the other hand, blue collar gig-matching platforms, which on paper have significant potential to formalise the huge informal sector, have often struggled to deal with operational hurdles and low consumer capacity to pay for quality, and thus have struggled to reach scale. Jobtech platforms in Africa need to do much more than simply “facilitate a match” between workers and available jobs — they need to fix more of the fundamental problems of a broken labour market, from a lack of demand, to skills deficits with the workers, to supply chain issues and more.

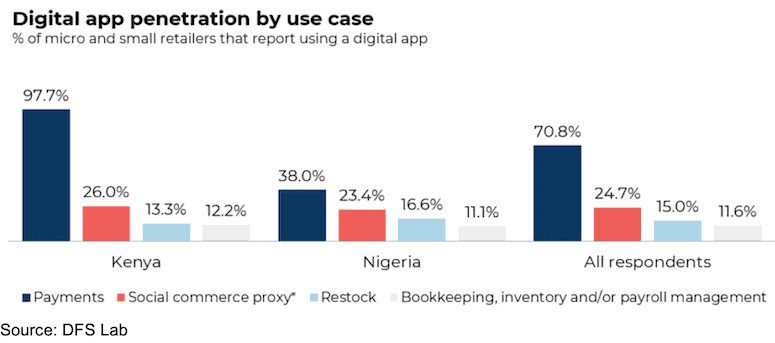

We have, however, seen success among platforms that meet informal workers where they are and support the digitalisation of African microenterprises (see Landscape Scan III – Digital Services for Microenterprises). A recent study from DFS Lab found that 70.8% of Kenyan and Nigerian micro and small retailers have digitised at least one aspect of their business operations — mostly payments — and the uptake of other digital functionality is rapidly increasing.

The digitalisation of microenterprise has made small businesses more efficient, increased sales and improved access to finance. The proliferation of platforms providing supply chain and financing for retail microenterprise has been partly driven by significant VC funding — Briter Intelligence reports that over $470 million was raised by 28 African business-to-business commerce startups between 2009 and 2022. But in recent months we’ve seen the expansion of such models beyond retail, as platforms are building the infrastructure for microentrepreneurs to thrive in a range of verticals. To take just one example, one of the Jobtech Alliance’s accelerator startups, Fitted, is an AI-enabled platform that allows fashion customers, tailors and fabric sellers to collaborate to produce exceptional quality outfits on time. It is currently building a digital platform which enables tailors in Nigeria — who typically operate entirely via pen and paper (and sewing machine) — to operate online, doing customer management and even measurements (through augmented reality), while obtaining supply chain support and access to finance.

While many of the platforms mentioned above are constrained by the limited local purchasing power in Africa, another exciting trend we’ve noted is the opening of the world’s jobs to African workers. Accelerated in part by the COVID-19 pandemic, platforms for digitally-delivered work have grown massively over the past few years (see Landscape Scan II – Platforms for Digitally-Delivered Work). These platforms can connect workers to service buyers across African borders and beyond — including in lucrative markets in Europe, North America and other developed countries. Global platforms tend to dominate the freelancing space, and quality control and skills gaps continue to be challenging, but we’re particularly excited by the gradual emergence of Africa’s global business services sector (traditionally called business process outsourcing). These businesses manage projects or contracts (largely for other businesses) delivered by multiple skilled or semi-skilled workers, working in areas such as call centre sales or customer care. Because they are more hands-on and work with larger contracts, these businesses can afford to build skills among their workers. While the sector traditionally has been dominated by large players, we also see an emerging trend in which smaller providers satisfy specific niches ranging from sales lead generation to customer success.

Tana is one such platform: a participant in our accelerator, it is a tech-enabled marketplace that connects global companies to vetted and trained remote team members on the African continent. To address the key questions about supply and demand within the global businesses sector, we’re helping them to explore which segments of employment are best suited to take on African talent, and to determine which types of lower-skilled tech roles are best suited for remote hiring. Answering these questions for Tana (and other such companies) will help connect Africa’s ample supply of educated youth with the growing global demand for the services they can provide. The big question that we will be following keenly over the next year is whether the emergence of generative artificial intelligence will limit that anticipated flow of lower-level digital work to Africa. Evidence suggests that this may already be happening, but new opportunities are likely to emerge.

One last trend we’ve seen, when looking across jobtech platforms in Africa, involves the consistent challenge (and opportunity) in the infrastructure required for these platforms to provide decent work for users across the continent (see Landscape Scan V – Digital Tools for Worker Enablement). This involves not only physical infrastructure, but also interoperability between the offline and digital world, and between the multiple platforms where workers might be “multi-homing” — i.e., utilising several platforms simultaneously. Few Uber drivers in Africa are just Uber drivers: Instead, they obtain gigs through Bolt, Glovo and/or half a dozen other ride-sharing and delivery apps. This increases their access to more available gigs, but also presents some key challenges. For instance, if a plumber’s entire experience is from gigs on different platforms, how does she aggregate her ratings across platforms to convince her next employer that she is a good plumber? How does she get insurance or loans, as financial services have traditionally been built for those with formal job contracts rather than platform-based gig work? Resolving these issues presents opportunities to build new businesses. Because these business models tend to build on top of other jobtech platforms (or indeed, function as foundational infrastructure which others can build on), they require jobtech to be more ubiquitous before they can achieve viability. However, there is an emerging cohort of platforms that are seeking to fill this gap globally, and we’re interested to see the role that different actors could play in building this essential infrastructure.

One of our accelerator portfolio startups, Power, is playing this sort of role. A Kenyan financial service provider, it is offering a suite of digital financial services (including earned wage access, savings, loans and insurance) to workers in Africa. As part of the accelerator, the Jobtech Alliance is developing a collaboration between Power and the Swedish-based data scraping platform Unveel, enabling it to offer its suite of financial services to gig workers on Bolt, Uber and Glovo in Kenya.

Africa’s jobtech sector is incredibly new, which is part of both the challenge and opportunity it presents. But as more people earn their incomes digitally and the industry grows, this category of platforms will become increasingly viable (and important) on the continent. First movers in developing key jobtech infrastructure will be well-placed to benefit if and when the sector scales, as the future of work continues to evolve in the region. And these companies will undoubtedly struggle with the dilemmas that are inherent to the broader sector’s growth. Yet despite these inevitable challenges, this nascent, still overlooked part of Africa’s digital economy will play a large role in providing employment for the continent’s growing population.

Michelle Hassan is the Kenya Country Manager and a Principal Consultant at BFA Global, as well as a Program Director at the Jobtech Alliance; Chris Maclay is Mercy Corps’ Program Director at the Jobtech Alliance; Bethany Hou is a Venture Building Associate at the Jobtech Alliance.

Photo courtesy of Muhammad-taha Ibrahim.

- Categories

- Technology