Innovating on the Pay for Success Model: How ‘Social Derivatives’ Can Unlock Everyday Giving to Incentivize Greater Impact

The most exciting thing about the social finance sector is that it is continuously innovating, with new approaches that range from scaling blended finance instruments to leveraging blockchain for transaction transparency. Apart from such macro-level innovations, stakeholders in the sector – be they philanthropic donors, investors, entrepreneurs or the end-beneficiaries – also innovate at their own micro-level. This can involve behavioural science “nudges” used by non-profits in crafting their funding strategies, or social entrepreneurs innovating business models that ensure double bottom-line impact. All these innovations, to varying degrees, target the common objective of attracting the right kind of capital to create a greater social impact.

Among these innovative approaches, pay-for-success (PFS) models have arguably remained at the forefront of social finance conversations for almost a decade now. PFS is an innovative financing mechanism, in which the investors and/or the investees are remunerated by outcome payers based on the outcomes (social and/or environmental) they jointly achieve. But while the immense potential of these models has become clear over time, challenges have also emerged. For instance, it can be difficult to ensure an economical structure, if the benefits of the PFS structure are outweighed by the costs of executing it. And it can be hard to find suitable outcome payers, especially in the case of social enterprises, where there is often a reluctance to “donate”to a company that generates a profit. Time and again, thought leaders have come up with innovative solutions to counter these issues and uncover persistent myths, such as those discussed in this NextBillion article.

But there’s a promising solution to the challenges facing the PFS model that hasn’t yet garnered widespread attention in the social finance sector, and it involves everyday giving. This type of charitable giving consists of individual donations from “ordinary” people (i.e.: not organizations/foundations, and generally not high net worth individuals), and it comprises a significant share of the total donations happening in any economy. In India, for example, individuals contributed US $5.1 billion in everyday giving in 2017 alone, supporting community, religion, disaster relief and other charitable causes. And despite these impressive numbers, India’s everyday giving market is still nascent as compared to the U.S., where individual donations amounted to $292 billion in 2018. We believe structures that can integrate the rapidly rising potential of everyday giving with PFS models would be game-changing for the social finance landscape. We have worked in this ecosystem for years, and we’ve conducted ample research on PFS models for for-profit social enterprises. Below, we’ll discuss how everyday giving donations could address the key shortcomings of these PFS models.

Substituting Large Donors with Small Ones Through Social Derivatives

One key benefit of linking everyday giving to the traditional PFS structure is that the donations can be channelled towards providing the outcome payment capital, whereby small-scale individual or “retail” donors pay for an intervention’s success. This instrument effectively brings the PFS model to individuals, who are substituting for the governments or large donor agencies that typically play the role of the outcome payer.

In implementing this approach, it would be essential to protect the interests and donated capital of these small retail donors. To that end, we’re proposing that a “Social Investment Option” (SIO) should be included as part of this instrument. An SIO would be a “social derivative” product that would protect the philanthropic capital of retail donors while incentivizing social outcomes. Just as the value of traditional derivative products is linked to the financial performance of an underlying asset, social derivatives would link retail donor capital to an intervention’s social impact performance. The option would entitle retail donors to recall their donations if the pre-determined social outcome targets are not achieved.

In this approach, the retail donor would transfer their donation amount and pay an SIO premium. The SIO premium would be determined by the administrative and impact measurement costs associated with implementing such a structure. This would create a structure similar to a principal protected note (a well-known financial instrument that guarantees a minimum return equal to the investor’s initial investment) – in this case let’s call it an “outcome-linked donation protected note” (OLDP note).

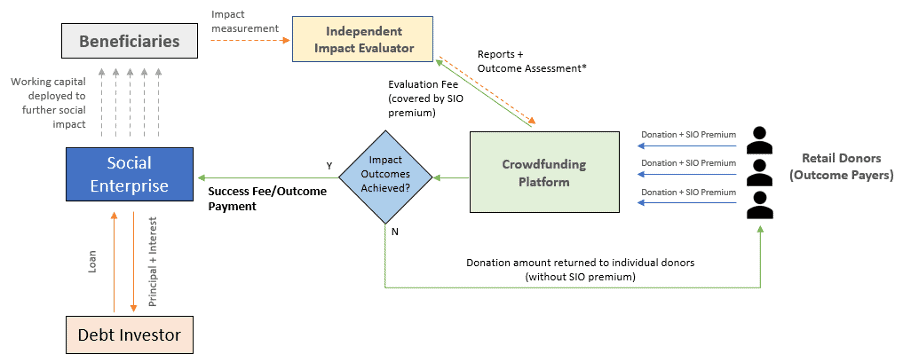

Below is an example of how this structure might look for a for-profit social enterprise that generates donations through a crowdfunding platform:

Figure 1: OLDP Structure for a for-profit social enterprise

The SIO premium is what donors would pay to get the option to pay the donation only if impact outcomes are met. The SIO premium, just like any other option premium, is not returned if the outcomes are not met – instead it is utilized to pay for the impact evaluation fee.

Advantages of Leveraging Social Derivatives in the Pay-for-Success Structure

A social derivative-based approach like the OLDP note structure has several advantages:

It opens up a new segment of social investors: There have been a handful of cases where retail donors/investors have participated in a PFS structure. One such example is a community bond launched in Scotland seeking small-scale investments from community investors to create a loan fund for local social enterprises and other community businesses. The OLDP note would help these sorts of approaches by unlocking a large and as-yet-untapped source of capital for funding initiatives which otherwise would never have access to large-scale social investments.

It can support investments that don’t fit the traditional structures: One challenge that we noted in our research on impact bonds for social enterprises is that, in a market like India, only a small number of funders are willing to invest as outcome payers in for-profit PFS models. Moreover, these outcome payers have specific mandates/focus areas. As a result, social enterprises or projects that do not fit these mandate(s) are currently unable to benefit from PFS instruments. OLDP notes, which can unlock a larger pool of outcome payers, can therefore support investments in a wider variety of industries and sectors.

It has the potential to be an economical and sustainable structure: In PFS debates around the world, an often-highlighted issue is the economics of blended finance structures. The impact measurement and technical costs for these structures can be enormous – sometimes greater than the outcome payment – and the sum of the outcome payment and technical costs often exceeds that of the investment amount. That means an outcome payer may have been better off giving the entire amount as a donation grant, rather than participating in a PFS structure. If such models are not economical, then how can they be sustainable in the long run? The OLDP note addresses these concerns. Like any other financing project, the note will have certain fixed costs (like impact measurement and structuring) and variable costs (like the success fee/outcome payment). The SIO premium paid by the donors would be utilized to cover these costs. This premium would thus be linked directly to the costs of financing the structure, providing economic viability with scale. It would also provide transparency, as the recipient organization/impact measurement agency would ensure regular reporting, because it would only get remunerated if the outcomes are achieved.

Challenges for the OLDP Note Structure

Despite its promise, there are several challenges that would need to be addressed in implementing an OLDP note structure. While most components of OLDP notes are similar to a traditional PFS structure, additional research and subject expertise are needed for streamlining retail donations and achieving the right costs vs. benefits balance for the structure. Since it could be difficult to individually source enough small donations to fund this approach, aggregators such as crowdfunding platforms that can gather the contributions of retail donors will be critical to the success of such an instrument. However, if the transaction costs involved with such crowdfunding platforms are materially high, that could be detrimental to the long-term sustainability of such structures. Also, since the structure involves the participation of retail donors, the engagement, reporting, measurement and communication must be transparent and meet high standards.

One area that needs further thought is how to price the SIO premium. If the SIO premium is paid but the outcomes are not achieved, the premium becomes a sunk cost for the retail donor, since they don’t get reimbursed for this amount (only receiving reimbursement for their actual donation). Therefore the question is, how do we ensure this premium is reasonable, when compared to the amounts given by these donors? Achieving scale is one answer, as a higher number of donors and the resulting increase in donations would mean that the SIO premium is a smaller percentage of the overall total donations. Matching donations from an institutional donor is another, as these matching funds would also increase the total donated amounts, reducing the percentage of donations that is spent on the SIO premium. Complex derivative structures such as autocallables traded in financial markets can also provide a model for ensuring reasonable premium costs for the donors.

Social impact organizations’ ability to implement this type of structure would, among other things, certainly be subject to the applicable laws regarding retail donations and crowdfunding – in both the donors’ and the recipients’ countries. We are researching ways to make a social derivative structure work in India, and would appreciate feedback and thoughts from the social finance community across the globe.

Akhil Pawar is currently a Project Manager at Yunus Social Business (YSB), where he is supporting the World Economic Forum’s COVID Response Alliance for Social Entrepreneurs. Geet Kalra is a Portfolio Associate at Yunus Social Business and also Director of the Social Business Youth Alliance in India.

Photo courtesy of Micheile Henderson.

- Categories

- Impact Assessment, Investing, Social Enterprise