A Roadmap for Scaling Up Renewable Energy in Island Nations: Three Success Factors for the Eastern Caribbean’s Transition from Fossil Fuels

The Eastern Caribbean—comprising Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, the Commonwealth of Dominica, Grenada, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, and St. Vincent and the Grenadines—has taken a beating during the COVID-19 pandemic. The region’s struggles are primarily due to a precipitous drop in tourism revenues, which account for as much as 73% of gross domestic product (GDP) in some countries, resulting in a 16.25% contraction in GDP in 2020. This is added to their extreme vulnerability to climate change and natural disasters, as seen in Tropical Storm Erika in 2015, Hurricane Maria in 2017, and the eruption of and subsequent ash fall from the La Soufriere volcano in 2020-2021 – each of which caused damages that amounted to a substantial portion of the region’s GDP and further harmed its tourism sector.

But diversification away from tourism is a challenge in large part due to high electricity prices which, combined with these countries’ small-scale economies, limit their competitiveness in other industries.

Done right, transitioning to renewable energy could significantly reduce the region’s cost of electricity. More distributed power generation would also support climate resilience, an imperative that is all too important for these islands. And, in some of these countries, limiting dependence on imported fuels would be beneficial in reducing mounting national budget deficits. Additionally, if developed strategically, the renewables sector could create valuable employment in a region which has struggled to provide technologically-minded and ambitious young people with attractive job opportunities.

However, to boost their renewable energy-based power generation and reap the associated benefits, Eastern Caribbean nations must overcome several obstacles. This article explores why it makes sense for the region to shift to renewables, and presents three success factors for achieving the transition – insights that could also be applicable to other island nations.

Renewable energy is critical to the Eastern Caribbean region’s resilience

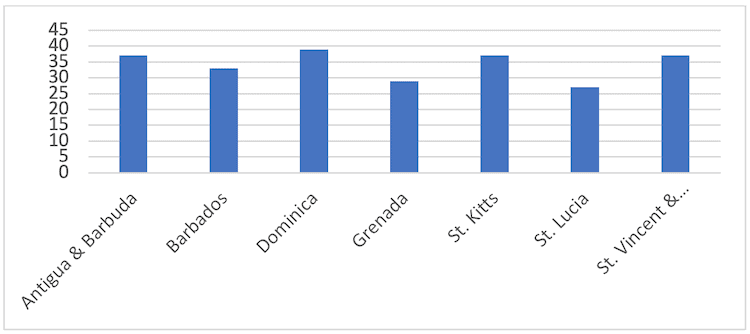

Electricity tariffs for commercial customers in the Eastern Caribbean nations range from US $0.27 to 0.37/kWh, with an average of US $0.33 – compared to an average of US $0.16 in Central America. By comparison, with the exception of St. Kitts and Nevis where they are 20%, system losses are fairly low at 11% in Antigua and Barbuda and below 10% elsewhere (5% in Barbados, 9.4% in Dominica, 7.2% in Grenada, 6.3% in St. Lucia, and 7.6% in St. Vincent and the Grenadines). Elevated power prices are primarily the result of a reliance on imported fossil fuels—in the region, diesel plants represent 75-96% of installed generation capacity—the cost of which is generally passed through to the customer.

Figure 1: Eastern Caribbean electricity tariffs, 2021, in US ¢/kWh

Source: Cable.co.uk Global Electricity Pricing Study, 2021.

Combined with the relatively high cost of labor and other inputs (given the region’s small, geographically dispersed markets and limited local economies of scale across which to spread expenses), the price of electricity is a burden for all sectors. Some 40% of Caribbean firms identify electricity costs as a major constraint to doing business. And to take just one example specifically in the Eastern Caribbean, hotel power bills can be as much as US $13 to $18 per room per day. As the region’s current economic engine, the tourism sector has a particularly urgent need to reduce operating costs to recover from pandemic losses.

Despite the potential, renewables uptake has been slow

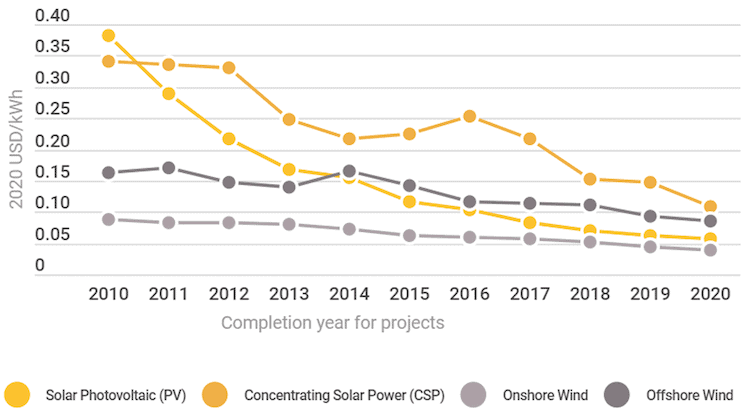

On the positive side, the levelized cost of energy (LCOE) of renewable-based power generation has dropped markedly worldwide. Since 2010, the price of offshore wind has declined by about 30%, onshore wind has fallen by 40% and solar photovoltaic (PV) has plummeted by 80%.

Figure 2: LCOE of selected renewable technologies, 2010-2020

Source: IRENA, Power Generation Costs Report 2020.

Falling costs of battery storage, a key component for addressing the non-dispatchable nature of solar and wind-powered systems in particular, provide an additional incentive to shift to renewables. Small islands’ power networks, like those in the Eastern Caribbean, are particularly dependent on utility-scale batteries, as they cannot easily connect with other grids. Other islands have demonstrated the importance of battery storage: For instance, in 2021 Hawaiian Electric achieved a renewable portfolio of 38% (up from just under 10% in 2010) — and most of this capacity has been coupled with batteries.

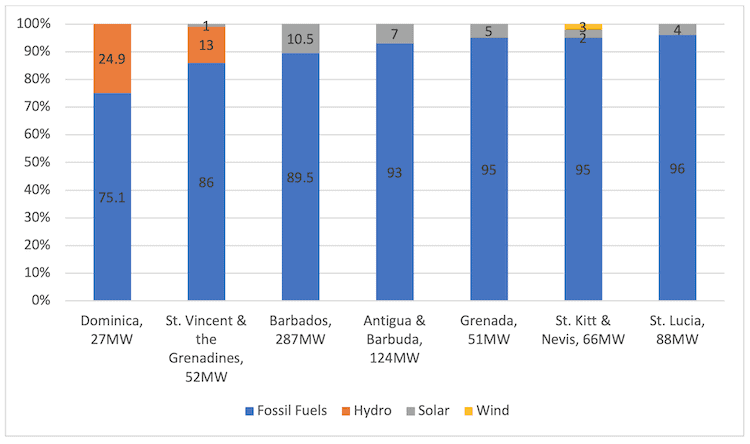

However, despite these price declines and the region’s abundant solar and wind resources, the portion of renewable technologies as a share of total installed capacity remains low. At about 25% and 14% respectively, Dominica and St. Vincent have the highest share of renewables-based generation capacity—but this all comes from hydropower. Solar PV as a portion of total installed capacity ranges from 10.5% in Barbados, to 7% in Antigua and Barbuda, and around or below 5% in Grenada, St. Lucia, St. Kitts and Nevis, and St. Vincent and the Grenadines. Only St. Kitts has onshore wind, which accounts for 3% of installed capacity.

Figure 3: Electricity installed capacity by generation technology, 2020

Source: US Department of Energy, Energy Transitions Initiative Island Energy Snapshots.

The reasons behind the relatively low adoption of renewables are hard to generalize. While each of the Eastern Caribbean nations has a distinct electricity sector structure, there are some common elements which may have slowed their contribution to the generation mix. For example, whether they’re public or privately-held, all of the area’s utilities are vertically integrated, holding exclusive licenses for generation, transmission and distribution; without competition, there may be few incentives for cost improvements. Most tariff regimes have a surcharge element, passing (sometimes dramatic fossil) fuel cost variations on to the consumer. Several have benefitted from concessional oil pricing under the PetroCaribe arrangement initiated by Venezuela in 2005, which has allowed many countries in the Caribbean to buy Venezuelan oil on credit and repay a portion of the purchase over a 25-year period at a 1% interest rate. When combined with historically higher capital costs of PV and wind as compared to diesel plants, all these factors may have also contributed to a reluctance to shift away from fossil fuels.

There are positive signs of a shift

However, despite these challenges, there are indications that a transition is underway. Encouragingly, there is high-level governmental support for renewables. As part of the Paris Climate Accord, Eastern Caribbean countries have set ambitious targets for their Nationally Determined Contributions. For instance, Barbados, Dominica and St. Kitts and Nevis are aiming for 100% renewables-based electricity generation by 2030. And Antigua and Barbuda have committed to installing 100MW of renewable energy generation capacity available to the grid by 2030.

If delivered upon using international best practice, these commitments could substantially reduce the region’s electricity prices and enhance its business competitiveness.

Beyond this, renewable energy is a core instrument of climate resiliency. As Hurricanes Maria and Irma demonstrated in 2017, islands are particularly vulnerable to network-wide power outages. Decentralized renewable-based systems, which can operate as interconnected mini-grids, are a better investment than costly efforts to bury extensive distribution lines – often across challenging topographies. This is an approach proposed in the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority’s integrated resource plan, which aims to establish eight networked mini-grids that are also able to operate in isolation, across the island.

Within the wider economic agenda, electricity generated from domestic renewable resources offers the additional notable advantage of reducing both the supply chain risks posed by reliance on imports, as well as the price volatility—oil prices increased by 50% from US $51 per barrel at the start of 2021 to US $86 per barrel at their highest point of that year, while at the time of writing, prices have spiked to US $120 per barrel. Furthermore, all the Eastern Caribbean nations have high public sector debt levels. Between 2019 and 2020, debt-to-GDP ratios increased from an average of 70% to as much as 111% (Dominica) and 150% (Barbados). In many circles, this has called into question debt sustainability, which impacts perceived borrowing capacity and, by extension, constrains governments’ ability to fund other development projects. In cases where they either procure or backstop these purchases on behalf of utilities, reducing fossil fuel-related bills could alleviate the burden on governments’ budgets.

Recent projects led by both national utilities and by independent power producers (IPPs) demonstrate the viability of renewables investments in the Eastern Caribbean. For example, in 2018, St. Lucia Electricity Services Limited’s 3MW La Tourney solar PV plant came online. In 2016, Barbados Light and Power Company commissioned a 10MW solar PV plant in Trents, followed by the addition of 20 MWh of battery storage in 2018. Several smaller locally-led PV and onshore wind IPPs have also been announced in Barbados. And, after years exploring alternative business models, the Dominica Geothermal Development Company is seeking to use commercial financing to develop a 7MW geothermal plant at Laudat that could potentially be scaled up to export power to the neighboring islands of Martinique and Guadeloupe through subsea cables.

Thinking strategically about IPPs could significantly speed up the transition

For the Eastern Caribbean to deliver on its renewable energy targets, there will need to be a significant change in the rate at which capacity is being added. The reality is that, under the status quo — e.g. the absence of very strong legislative frameworks — power utilities’ incentive and appetite to invest in renewables remains varied. From an investment planning perspective, shifting to grid-scale solar PV, wind or battery storage infrastructure involves weighing the often-high operating costs of fossil fuels (that can be passed through to consumers) against the typically large capital expenditures required for renewable technologies (the financing of which depends on a number of factors, not least of which being the amount of debt their balance sheets can handle). In this context, and as evidenced by the handful of private developers that have entered the market to date, under the right conditions, independent power producers operating side-by-side with national utilities could meaningfully speed up the transition.

Although each of the region’s nations are small, their collectively bold renewables penetration targets could conceivably attract top-class international IPPs, potentially significantly lowering tariffs. For instance, the 51MW Paradise Park solar PV plant in Jamaica, developed by Neoen, MPC Caribbean Clean Energy Fund and Rekamniar Frontier Ventures, with financing from FMO and Proparco, is selling power to Jamaica Public Service Company Limited on a 20-year power purchase agreement at US $0.085/kWh.

Capital costs for a ground-mounted PV plant in an island context could reach US $1.5-2 million per MW, excluding storage. Developers typically seek opportunities of at least US $30-50 million, roughly equivalent to 15-30MW. Combined, the region could offer close to 1,000MW of new capacity by 2030, translating to an investment opportunity of well over US $1 billion – though there’s one caveat: As projects are spread across several islands, without aggregation, they would likely experience the disadvantage of being smaller than those in larger countries in the Latin American and Caribbean market that are vying for the same partners’ attention. This would become even more apparent for newer technologies, such as offshore wind, green hydrogen and, in some cases, onshore wind, for which projects are more complex and development costs are typically much higher than for more mature technologies such as PV. So some grant or concessional funds would likely be needed to undertake pre-feasibility studies, make projects bankable enough to attract top players, and cover transaction costs. For instance, Jamaica’s 36MW BMR Wind Farm was made possible through a US $62.7 million financing package, which included US $10 million in blended concessional financing from the IFC-Canada Climate Change Program and a senior loan of US $10 million from IFC, with the remainder coming from the DFC.

Success factors for achieving the Eastern Caribbean’s renewables targets

Three essential actions will help countries in the Eastern Caribbean attract serious, experienced developers with a view to supporting utilities in advancing their timely transition to renewable energy.

Define a vision for resilience, then an energy sector plan: First, in the context of a holistic resilience agenda, it’s important for each country to clarify its required energy capacity additions and prioritized technologies. Fundamentally, electricity is an enabler of socio-economic—and indeed, sustainable—development, and not an end in itself. The starting point for developing renewables, therefore, should be a clear vision of a country’s long-term development aspirations, taking into consideration the climate crisis and economic challenges that the islands are facing. In which sectors does the government want to grow employment going forward? Does the country aspire to shift to niche, eco-tourism – or to move away from tourism to develop more high-tech industries? In countries where youth unemployment and the outward migration of skilled, working age citizens is a challenge, how might opportunities in technology-forward sectors, such as those linked to renewables, be cultivated? How can these countries leverage their vast marine territories sustainably to support long-term development agendas? Given the small-scale issue, where could multiple countries in the region benefit from acting in lock-step with one another, instead of defining their own separate national imperatives?

Once this wider vision is articulated, the government must use it to develop a robust least-cost generation plan reflecting resources and vulnerabilities. Here, policymakers must assess and define the role each relevant technology is expected to play in the renewables transition. Nations with scant hydro or geothermal resources, for example, will need more battery storage to address intermittency and ensure grid stability. For some countries, natural gas may need to serve as a bridge, while for others, green hydrogen production based on offshore wind energy might be a key part of the long-term vision. Other nations may pursue a highly decentralized power-generation model in which households and businesses produce electricity for themselves and sell the excess to the grid. The generation component aside, as part of this plan, policymakers should also clarify pertinent climatic and other environmental risks affecting their transmission and distribution network resilience, determine how these will be addressed, and outline expected standards of service for this part of the network.

Clarify how the private sector can enter the market: Second, it’s essential for countries to define their desired business models for realizing new generation additions. Potential investors need to know basic information, such as how much renewables capacity will be required over which timeframe. They also need to know whether the government will be procuring this capacity through auctions, or if unsolicited proposals are permitted. Depending on the approach, public private partnership or IPP frameworks with risks appropriately allocated to the parties best-placed to mitigate them will be needed. Concurrently, governments must also address policy, regulatory and procedural barriers that might get in the way of the market taking seriously and responding efficiently to a call for private sector participation.

For example, in some cases, existing environmental and social impact assessment requirements may be designed for diesel plants, and will therefore need to be adjusted to reflect the very different specificities of solar PV facilities. In others, feed-in tariff regimes may be calculated to support domestic market participation in the renewables sector. However, if these tariffs are set significantly higher than what could be achieved if capacity additions were auctioned on the market, allowing for both domestic and international players to compete, the result could be an undue burden on the end consumer – one of the very issues that renewables could help to improve. Domestic participation is important, and can be achieved by other means, such as requirements for joint ownership with incumbent utilities or local developers, without negatively impacting electricity prices. Unless potential bottlenecks are identified systematically across the energy value chain, it will be hard to attract the necessary investment to the sector, as developers cannot determine if or where they might fit in. This can constrain the solution space and delay countries’ achievement of renewable energy targets.

Pursue an integrated and focused approach to implementation: Finally, and critically, to make good on their ambitious renewables commitments, Eastern Caribbean governments must pursue implementation with a laser focus and develop solid, actionable delivery roadmaps. These should include distinct milestones which are reported on transparently, and against which the performance of those tasked with project roll-out is measured. Appropriate staffing of the units responsible for the sector’s scale-up is also critical, as is ensuring adequate operating autonomy: Entities or individuals mandated with the strategic task of adding large amounts of generation capacity to the power system as part of a comprehensive resilience agenda should not be unduly drawn into day-to-day sector activities or suffer unnecessarily bureaucratic decision-making processes that delay the end game. Ideally, where the renewables sector comprises a significant part of a country’s wider national resilience and economic growth agendas, the team responsible for advancing this transition should report to the highest level of government. Experience from “delivery units” mandated with advancing strategic capital projects of this nature around the world has shown the value of such foundational ingredients.

Governments would also benefit from following a “one-stop-shop” model, in which large projects involving new technologies or sizable investment volumes are implemented through a structured approach. One such example is South Africa’s Renewable Energy IPP Procurement Programme which, since its inception in 2010, has attracted developers and financiers from around the world, adding over 6,000 MW of primarily solar PV and onshore wind capacity to a previously supply-constrained power grid. Of particular note is the program’s focus on community ownership and local jobs creation, which are criteria included in the evaluation of bids: As a result of this effort, renewable energy projects developed in the Eastern Cape region of South Africa are estimated to have created over 18,000 jobs.

Another example of a holistic approach is the World Bank Group’s Scaling Solar Initiative: Focusing on developing the market for grid-connected solar PV in countries that may not otherwise have been top-of-mind for world-class IPPs, it supports governments in everything from selecting a site to tendering, drafting project documents (including bankable power purchase agreements), and offering competitive financing to pre-qualified bidders. Zambia, a country that was not initially on the radar of many renewable energy developers, was the first nation to implement the initiative in 2019, leading to the commissioning of its first 54 MW of solar PV. Providing power at US $0.06/kWh, this was one of the lowest generation tariffs in Africa at the time. A similar comprehensive approach is being replicated to help countries secure competitively-priced power in the wind and mini-grids sectors by the World Bank Group and by IFC, respectively.

Investors respond to markets with clarity, certainty and transparency, along with government commitment – this drives competition, quality offers and lower prices. If the three preconditions discussed above can be met, the Eastern Caribbean’s renewable energy transition will have a higher likelihood of attracting financing – and greater overall prospects for success.

————————–

Note: The author would like to thank Judith Green, Nuru Lama and Don Purka for their valuable input to this article, and Lucy Shaw for her research contribution at the conceptualization stage.

Pepukaye Bardouille is Resilience Lead within the Global Upstream Infrastructure Unit at the International Finance Corporation (IFC).

Photo credit: Pepukaye Bardouille

- Categories

- Energy, Environment, Investing