Smallholders as Customers, Not Pupils: Making the Case for Good Agricultural Practices

Since the early 2000s, governments, commercial firms, NGOs and international organizations have expanded the market incentives for adhering to Good Agricultural Practices (GAP), such as incorporating GAP certifications into supply chains and procurement decisions.

These practices, addressing “environmental, economic and social sustainability for on-farm processes,” as the FAO defines them, can bring with them the promise of improved food safety, food quality and environmental stewardship.

But not all producers have benefitted equally from the market advantages of GAP adoption. The growing prevalence of GAP requirements is a risky business for smallholder farmers with low capacity to implement new production and rising standards. After all, market advantages of GAP adoption also come with higher costs and uncertain returns on investment that can exclude smallholders from seizing market opportunities.

In light of these trends, smallholder farmers face a business investment decision involving substantial risk and complexity. Will they be better off aspiring to access GAP-certified markets if they must implement costly practices and standards?

embracING a business orientation in gap promotion

The short answer to that question is “yes” – but with some caution. Companies, NGOs and other market actors seeking to align GAP promotion efforts with farmer behavior and perceptions of value and risk should broaden their approach beyond a strictly agronomic focus on how to grow. Promoters should also include a business case perspective that conveys the value proposition of GAP adoption to smallholder farmers.

Expanding on this perspective in “A Customer Centric Lens for Good Agricultural Practices,” Nick Ramsing advocates three key components of smallholder decision-making to promote GAP adoption:

- Emphasize the market context and align GAP promotion with opportunities in specific markets and product requirements;

- Leverage a customer-centric perspective to test and validate assumptions about smallholder decision-making; and segment farmers based on shared needs, preferences and production practices;

- Adopt a business orientation to promote the smallholder business case and value proposition alongside agronomic practices.

reimaginING gap adoption as a business investment decision

The decision to incorporate GAP or maintain existing growing practices is not strictly an agronomic judgement—it’s also about maximizing net revenue. GAP adoption may enhance access to markets, but smallholders will likely need to invest in improved equipment and infrastructure, upgrade record-keeping systems, or acquire specialized labor. Farmers are rightfully concerned about the risks of allocating scarce household resources to upgrades, and about whether they can maximize returns on investment.

The simplified net revenue model below is a helpful approach to understanding smallholder business decisions. The model accounts for market incentives (expressed as market transactions data) and agronomic influences (based on smallholder estimates of production costs). Net revenue reflects whether smallholders will credibly profit from GAP investments based on the perceived value of recommendations. It’s both a useful segmentation tool and a compelling component of a smallholder business case.

This method is helpful for appreciating different drivers of smallholder decision-making, but in order to test our hypotheses, we need to look at customer experience.

what we don’t know about smallholder decision-making (and how to find out)

A customer-centric approach requires engaging with smallholder farmers as customers rather than beneficiaries of know-how. “Customer centricity defines a perspective and mindset that puts the customer at the center of all business decisions, business processes and actions,” as explained in “Starting Small: Pathways to Customer Centricity”.

Customer centricity has been essential to MEDA’s INNOVATE initiative, which focuses on assessing the potential of non-traditional finance for large-scale adoption of agricultural innovations among smallholder farmers. INNOVATE works with partners across South Asia, South America and East Africa to collect farming business data, use experimentation to validate assumptions about smallholder segments, and identify pathways to GAP acceptance.

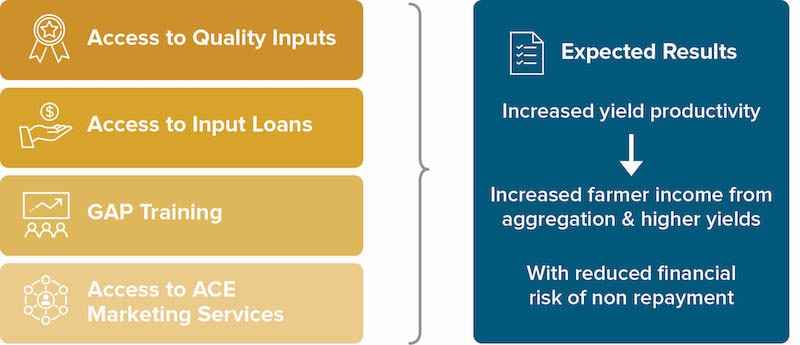

From 2015-18, Agronomy Technology Limited (ATL) implemented the Chithumba model, a non-traditional finance mechanism targeting smallholder soy bean farmers in Malawi as part of the INNOVATE initiative. The Chithumba model delivered GAP training as part of a services bundle alongside loans, quality inputs and marketing services. ATL’s Case Study of the Chithumba Model hypothesized that bundled services would encourage GAP adoption, increase sales and expand marketing services usage throughout the growing season.

The Chithumba Model

Instead, the study captured “substantial differences” between farmers’ stated GAP demand and their actual application of it. While input loan repayment rates exceeded 90% across all farmer groups, ATL documented low uptake of GAP recommendations and low usage of marketing services. Similarly confounding, 99% of clients perceived GAP training as useful, but only 21% fully adopted the recommendations, as emphasized during a learning webinar on GAP promotion. Top cited explanations included high labor costs, low trust in information accuracy, and risk of cash flow disruption due to delays between upfront GAP investments and increases in post-harvest sales.

ATL’s experimental approach revealed gaps in our understanding of smallholder decision-making, particularly when stated preferences significantly differ from actual behavior. Combining these techniques with customer centricity in data collection and analysis helped to unravel the complexity of smallholder decision-making and build a better business case for GAP adoption.

From learning to practice

GAP fittingly remains a focus area for many donors, development organizations and market actors, given the potential gains to agricultural productivity and rural household incomes in emerging markets.

Still, the time and effort needed to understand farmer perceptions and empathize with smallholder business models is no small feat.

To help streamline practice in this area, we’d like to conclude with principles drawn from INNOVATE’s experience implementing adaptive GAP projects:

- On building your methodological toolkit: Advanced data science techniques can enhance targeting by grouping farmers based on shared implicit behaviors. Start with analyzing farm, production costs and revenue data, and then iteratively include demographic and behavioral influences. (We suggest learning about different types of smallholder data and clustering techniques, and consulting a roadmap for identifying pathways to GAP adoption).

- On adapting and pivoting models based on learning: Turn promising pathways into small pilot projects guided by experimentation, hypothesis-testing and learning. Replicate and scale activities that work, and continuously adapt to new learning.

Incorporating these perspectives and practices can help market actors to promote GAP adoption at scale, streamline existing service delivery and identify new offerings.

Ben Fowler is Co-Founder and Principal at MarketShare Associates (MSA).

Clara Yoon is Project Manager at Mennonite Economic Development Associates (MEDA).

Top image courtesy of Swathi-Sridharan.

- Categories

- Agriculture