The Supply and Demand Dilemma in COVID-19 Vaccine Manufacturing: Could Lessons from the Fashion Industry Provide Ideas for a Solution?

Expanding COVID-19 vaccine manufacturing capacity is essential to stopping global transmission and halting the emergence of new variants of the virus. But efforts to achieve socially optimal manufacturing and supply have been hampered by uncertainty about the long- and medium-term demand for vaccines, and challenges affecting the supply of key inputs for manufacturing both the vaccines and ancillary supplies for vaccination. In response, multiple efforts are now underway to increase and diversify manufacturing capacity and reallocate or donate surplus doses.

The obstacles facing COVID-19 manufacturing and distribution are multifaceted. Medium-term demand for existing vaccines is highly uncertain because of emerging data on their differential efficacy against new viral variants, debate over the need for additional doses in developed countries, and the fact that second-generation vaccines are currently in the pipeline of approval/authorization. COVID-19 vaccine manufacturers (including contract manufacturers like Lonza, Emergent and Catalent) have to plan their capacity, production campaigns and sourcing in this environment of high demand uncertainty. On top of that, the demand for ancillary supplies required for vaccination — e.g., specific types of syringes and vials — also keeps changing.

The value of COVID-19 vaccines is truly beyond compare, in the sense that there are few products that create such immediate health, social and economic benefits. However, the manufacturing and delivery challenges involved in bringing that value to billions of people around the world are similarly unparalleled. Public health experts, biopharma and medtech manufacturing experts, along with supply chain/logistics experts, have all been working tirelessly to solve some of these challenges. But, since the best ideas sometimes come from outside an industry, we wondered whether we could learn from other industries that manage similar dynamics of demand and supply uncertainty and use those insights to better match demand and supply and resolve supply bottlenecks.

To that end, we turned to the fashion apparel industry. A closer examination shows that the distance between supplying a life-saving vaccine and the latest trend in streetwear is not that great.

How the Fashion Apparel Industry Balances Supply and Demand

The fashion apparel industry is characterized by immense product variety, volatility in product demand due to changes in consumer preferences (just think of how fads come and go), and a manufacturing base that is spread out globally. Its replenishment cycles (i.e., the processes by which stocks are resupplied from a central location) are long, because much of the manufacturing takes place in low-cost production bases that are far from major retailers. Most fashion brands order what they will need six to eight months in advance, and the selling seasons are usually short — i.e., two to four months. Each fashion brand has to develop relationships with many suppliers/contract manufacturers and provide them sufficient incentives to be dynamic — that is, to expand/reallocate capacity in times of need. That way, when that new type of denim is selling like hotcakes and the company needs a LOT more of it, the supplier is willing to put all hands on deck, work three shifts and add workers quickly.

How do the large fashion apparel firms manage this rapidly changing complexity and still manage to provide us with our favorite shirt, or that suddenly in-demand dress? Do they give large contracts to each of their manufacturers? Do they rely on their long-term relationships with their contract manufacturers? Do they call their contract manufacturer/supplier in Bangladesh, Honduras or Sri Lanka in the middle of the night when the previous week’s sales data tells them those athleisure pants, of which they ordered too little at the beginning of the season, are now the hottest fashion fad?

The answer is yes, they do — but only sometimes. Most of the time, someone else plays this role for them — a supply chain infomediary that provides a combination of information and contracting support. In this industry, a specific infomediary is usually involved: A company called Li & Fung manages the supply networks for most major fashion brands and retailers. This company is not an ordinary broker which helps connect a buyer and a seller. It also brings together information and contracting in a way that creates stronger incentives for contract manufacturers/suppliers to switch production as the fashion brand’s preferences change.

Let’s take a hypothetical example: Without Li & Fung, a very specialized embroidery-based manufacturer in Bangladesh may see their business go completely dry in a given year because a fashion label, say The Limited, decided to take embroidery off its fall fashion line. Li & Fung, however, manages these processes for almost all players in the industry, so the company always has other buyers to refer to that manufacturer. In return for providing stability of demand, the embroidery manufacturer owes Li & Fung in-kind support when future needs arise. So next season when a fashion label, say Gap, needs to urgently get more production for an embroidered shirt, the Li & Fung account manager calls the embroidery manufacturer, and they are happy to add an additional shift or do everything in their power to fulfill that demand.

The contract manufacturers/suppliers are happy because they get more stable demand. The fashion brands are happy because they get the flexibility and responsiveness they require, without the need to be stuck in long-term contracts with many dozens of suppliers, knowing that their demand environment is constantly changing.

Working as the information and contracting intermediary for multiple fashion brands gives Li & Fung greater flexibility in making commitments for future business to contract manufacturers/ suppliers — along with the ability to meet those commitments by always finding fashion brands and suppliers to match. Notably, Li & Fung doesn’t own any inventory or produce anything: It is an information and contracting entity that reduces risk through pooling and better advanced planning.

Exploring New Models to address Vaccine Supply and Demand

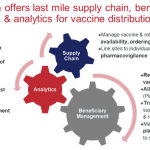

The contracting for COVID-19 vaccines and vaccine supplies is managed by country governments and their specially designed programs — e.g., Operation Warp Speed (OWS) in the U.S. In many low- and middle-income countries, this is managed by global initiatives like COVAX, CEPI and UNICEF. Given this existing system, how do vaccine developers get a flexible supply from the contract manufacturers working on their specific vaccine types? Do the vaccine developers working with OWS, COVAX, CEPI and UNICEF do what Li & Fung does? The answer is yes — but they only do parts of it. In most cases they have to provide longer-term contracts to get the required flexibility and favorable pricing from their contract manufacturers/suppliers, because there is no central information and contracting intermediary.

Again, it is not so much about who actually buys the vaccines on behalf of a country: It is more about who manages the information and handles the contracting with the vaccine manufacturers and the ancillary material suppliers. Could COVAX and CEPI, the only groups which currently have the information and competency to carry out such a role, act as the Li & Fung of the COVID-19/pandemic vaccine supply chain? CEPI and COVAX have recently established a COVID-19 vaccines supplies marketplace, which is one step in that direction.

The fashion apparel industry might also provide other models that could be applied to vaccine manufacturing. For instance, some apparel companies use the strategy of “spackling,” in which they maximize the flexibility of their manufacturing capacity by producing custom products, while also maintaining their production schedule by manufacturing more routine products when custom orders aren’t available. This fills the gaps in their custom order schedule, allowing them to manage the uneven demand for these products by spackling them with other products with more consistent demand. The custom messenger bag manufacturer Timbuk2 built a very profitable business manufacturing custom bags in the U.S. using spackling. If this approach were used for vaccines, a (future) strategy could involve a manufacturing plant spackling COVID-19 vaccine booster doses with a seasonal flu vaccine or other vaccines which have seasonal demand or can be stockpiled.

But regardless of which solutions we pursue, it’s essential to consider their long-term value. We cannot afford to fall into a build and decay approach, in which we invest heavily in creating manufacturing capacity during the current pandemic, only to have that capacity go unused — and eventually mothballed — in the future. To avoid this, we believe there is tremendous value in resolving information asymmetries and achieving better contracting through a supply chain infomediary that acts on behalf of a large number of purchasers of COVID-19 and other vaccines.

We fully recognize that vaccine manufacturing is a complex, global process. Manufacturing facilities cannot expand capacity overnight by adding a shift, nor can they always switch from one product to another as easily as their counterparts in the garment industry. So not all ideas from other industries apply to vaccine manufacturing. But nevertheless, it’s important to remain open to the approaches used by other industries to manage high demand and supply uncertainty. If even one or two of these ideas can contribute to the design of a better system that prepares our vaccine supply chains for future pandemics, it will be worth the effort.

Prashant Yadav is affiliate Professor of Technology and Operations Management at INSEAD and a Senior Fellow at the Center for Global Development.

Rebecca Weintraub, MD is on Faculty at Harvard Medical School. She is Director, Better Evidence at Ariadne Labs and is an Associate Physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Tom Johnston, MBA, is an executive-level biotech and vaccine industry consultant to CEPI and others.

Photo credit: UN Women Asia and the Pacific

- Categories

- Health Care