Creating Sustainable Last-Mile Distribution for Beneficial Products: Two Network Archetypes (and How They Can Scale Up)

Last-mile distributors (LMDs) play a critical role in making beneficial goods accessible to underserved populations in hard-to-reach areas. The Global Distributors Collective (GDC) defines LMDs as organizations that sell products that contribute to the Sustainable Development Goals, and that are primarily focused on distribution to last-mile households. While these organizations only represent a small share of the overall distribution sector, they are often the only ones that carry new, essential products into remote areas, thus playing a key market creation role. They also help bridge the access gap, in particular in places where retail and local social organizations (such as microfinance networks) do not reach. LMDs can vary greatly in size, sectors of activity, business models and viability levels. The over 200 LMD members of the GDC, which aims to support the LMD sector, are a testimony to this, as detailed in the 2019 “Last-mile Distribution: State of the Sector” report.

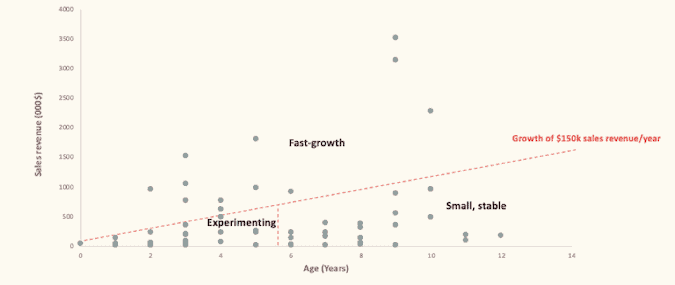

In order to better support this sector and leverage its full impact potential, we at the GDC realized that we needed to better segment the variety of models covered by the term “LMD.” The first segmentation we explored was based on sales revenues and growth (see below). This has helped investors looking to differentiate between early-stage, stable and fast-growth companies. However, we soon realized it was not enough. It did not enable us to do the match-making that key stakeholders — e.g., funders, product manufacturers and service providers — were looking for. Further, it did not enable us to refine our support to LMDs, as it did not sufficiently account for their different models and needs — nor for their different possible paths to sustainability.

Distribution of GDC LMDs by segment, based on age and annual sales revenue. Source: 62 GDC members interviewed in 2019

Two archetypes of LMDs emerge from the data provided by GDC members and previous LMD research. These correspond to different initial impact and business philosophies, leading to different operating models, growth trajectories and sustainability mechanisms. Rather than two distinct segments, they are two ends of a continuum of models. At the GDC, we are now using these archetypes to develop more tailored offerings for our members. In turn, we hope that this segmentation can help others interested in the last mile to more easily identify, leverage and support suitable LMD partners. We’ll discuss these archetypes and their unique characteristics and needs below.

Two Last-Mile Distributor Archetypes

ARCHETYPE 1: “Local Livelihood” LMDs, which train and support village-level entrepreneurs, often women, in becoming sales points for a suite of beneficial products.

- Their theory of change is as much about their impact on their customers as about the number of income opportunities they create (they often advertise both on their websites).

- Their model relies on building local networks of sales agents in the communities where they live and work. Agents are mostly part-time, which suffices to serve their small catchment area — often only their own village.

- Intrinsically limited by their small geographical outreach and the purchasing power of their area, these agents quickly saturate their market if they sell durable goods, and are only able to sell low volumes if they sell fast-moving consumer goods. Previous analysis by Hystra on dozens of LMDs — further confirmed by examples within and outside the GDC membership — shows that these LMDs can, at best, make US $6,000-10,000 in yearly sales per agent (per full-time equivalent).

- To compensate for low sales volumes and ensure sufficient income for their local agents, some LMDs have invested in making their salesforce more mobile — for instance, by providing them with bikes. Beyond such adjustments, the management teams of these LMDs are often focused on raising grants and/or scouting for new income sources. Many have diversified into services that leverage their last-mile networks, such as testing products, conducting field surveys or awareness campaigns, organizing field immersions, or offering (paid) internships.

- As a result, with salespeople generating limited cash and management focused on identifying new funding sources, these LMDs’ sales growth trajectory is often relatively slow. In our GDC member analysis, these models typically did not achieve more than US $150,000 in sales revenues per year of existence (e.g., if the company is four years old, they would sell less than $600,000/year). Hence, they were classified either as “experimenting” or “small and stable” companies in the graph above.

- Conversely, some of these distributors have seen impressive geographical expansion thanks to (grant) funding raised for specific projects in new regions.

- Further, these models can have a transformational impact on the communities they work in, by supporting local entrepreneurship and by providing a suite of products and services over time to many local clients (as opposed to “only” selling one product to a few clients and moving on).

- Leveraging this impact, the founders of the largest LMDs in this category, which work with thousands of part-time last-mile entrepreneurs, such as Solar Sister or Dharma Life, play a key advocacy role, thus increasing the visibility of last-mile communities and solutions internationally. Solar Sister, for instance, relies on a network of around 2,000 active part-time independent entrepreneurs. Trained in business, technology and leadership skills, these entrepreneurs operate clean energy businesses, primarily using door-to-door sales. Solar Sister has a hybrid revenue model, with revenues from distribution covering the costs of the last-mile distribution business. It uses grants and donations to boost its impact on female entrepreneurs and underserved last-mile communities, and to enable its advocacy role, which includes open-sourcing its insights to help mainstream gender inclusiveness.

- Funding-wise, these companies typically require grants for several years, until their scale draws the interest of suppliers and other companies. At that point, they can grow increasingly sustainable through contracts with large accounts.

- In terms of future trends, they tend to widen their basket of products over time, including recently by leveraging e-commerce and transforming their sales agents into local aggregators of online orders. This last move could be a game-changer for LMDs close to this archetype: For instance, it already enabled Frontier Markets to close a round of pre-Series A funding in 2020.

ARCHETYPE 2: “Dedicated salesforce” LMDs, which work with dedicated sales agents who sell a small product range to a large number of clients over wider geographical areas.

- Their theory of change is focused on reaching as many clients as possible, as efficiently as possible. They quantify their impact mostly in number of products sold or households reached.

- Their agents tend to be full-time or close to it. Each of their sales agents covers a much larger area than the Local Livelihood LMDs.

- As a result, these LMDs tend to have fewer salespeople, each selling significantly more per year than those of the local network categories. Previous Hystra analysis and GDC data show that best-practice organizations in this category (such as Zonful Energy, Ecofiltro and Mwezi) can reach average sales of over US $10,000 and even $20,000 per year (per full-time equivalent). For instance, Ecofiltro is an LMD selling water filters in Guatemala. To date, it has sold over 500,000 filters, 60% in rural areas, and has reached profitability through sales revenues and carbon credits. While it has established a solid urban market through traditional and modern retail, its rural, last-mile strategy relies mostly on a limited salesforce of 12 full-time mobile agents, each selling tens of thousands of dollars worth of filters every year, initially directly to customers, and now also through retailers.

- With such productivity, these sales agents and LMDs themselves do not need side income opportunities. Dedicated Salesforce LMDs hence have less diverse income sources (often none beyond sales).

- As a result, these sales agents typically “pay back” for their recruitment and training costs relatively fast, management has more time to focus on growth, and these businesses, when successful, tend to scale up faster than successful Local Livelihood ones.

- Among the GDC “fast growth” members (defined as those having reached sales revenues of above US $150,000 per year of existence) identified in the chart above, 11 out of 12 were close to this archetype. Given their models, all had managed to raise equity (except for one whose growth was self-funded).

- For LMDs close to this archetype that sell low-value items (e.g., solar lights, improved cookstoves or water filters), a typical evolution, when markets mature and the direct marketing piece of their model becomes unnecessary, is to move from selling directly to consumers to selling to retailers. Some Dedicated Salesforce LMDs also work with retailers from the start (e.g., Essmart, which offers a large portfolio of new products on catalog, available from chosen retailers). Actually, close to 70% of the GDC’s “fast-growth members” identified above leverage retail shops as a separate sales channel — or as local delivery and payment points for their products.

Understanding Last-Mile Distribution Models

So what can each of these archetypes bring to manufacturers, service providers, funders and other organizations looking to work at the last mile?

Local Livelihood LMDs can be powerful partners for organizations interested in exploring a new market, testing a new product or business model, or reaching remote communities that they are already connected with. They are, however, unlikely to be able to individually scale up a partner’s product or service beyond their existing outreach, unless they benefit from dedicated (grant or project-related) funding to expand to new areas. At the GDC, we will be looking for ways to support these models in finding new income opportunities and partners that can enable them to both leverage and grow their existing networks. We will also be exploring aggregation opportunities that can help them generate economies of scale and improve their sustainability.

Dedicated Salesforce LMDs are likely to only take on additional products or try new services if those are synergistic to their current offering. In that case — and in that case only — they should be able to scale these products and services up relatively fast. They are unlikely to take on consulting projects or partner with companies to test new products and projects beyond this scope. They are, however, good candidates for more commercial fundraising. At the GDC, we will be looking for ways to support these models in continuing to improve their efficiency, and in raising equity and debt to scale.

Finally, we fully acknowledge that there are models in between these two archetypes. They include initiatives like Unilever’s Shakti Project, which sells fast-moving consumer goods in rural areas; early Local Livelihood projects like Easysolar, which have built recurring revenue streams through an extended product range sold via cash-based PayGo; and ecommerce businesses like Frontier Markets. Stay tuned for subsequent articles about these new models.

Lucie Klarsfeld McGrath is a Partner at Hystra and co-founder of the Global Distributors Collective.

Photo courtesy of DFID – UK Department for International Development.

- Categories

- Uncategorized

- Tags

- distribution, scale, SDGs