‘Back in the U.S.S.D.’: Most Smartphone Owners—Especially Women—Don’t Use Apps for Financial Services

Over the last 15 years, the basic mobile phone has revolutionized communications and finance across emerging markets of the Global South, bringing dramatic new capabilities to broad swaths of the population, including underserved geographies and socioeconomic groups.

But the future, we are told, belongs to smartphones. Unlike basic phones, which are limited to voice and text, ever-cheaper and more capable smartphones promise to provide the first truly global computing platform for all kinds of new use cases. Large color touchscreens display vivid media, GPS and other sensors offer personalized data and guidance, and an enormous ecosystem of native apps provide near-limitless user experience possibilities, all tied together and enabled by internet access and data services.

This ongoing transition from basic and feature phones to smartphones affects virtually every sector, from healthcare to education to transportation. But it is especially salient in financial services, where first-generation mobile money services (which can work on any phone) are being superseded by an explosion in mobile banking and fintech offerings that are often predicated on smartphone apps and internet access.

Images: Samuel Ojo/ Positive Insights

As with every large-scale technological shift, it’s instructive to examine to what extent this transition will exacerbate existing inequalities. Worldwide, women are less likely to have access to financial services, and less likely to have access to mobile phones of any kind. Could the transition to the smartphone era of financial services help to narrow the financial inclusion gap? Or will it widen it?

With financial support from The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Caribou Data contributed to a comprehensive study of how payment system design — specifically, the Level One Project principles — could impact gender bias in digital financial services. While other project workstreams by Caribou Digital conducted field interviews and focus groups to understand customer attitudes and behaviors more broadly, our workstream at Caribou Data focused exclusively on smartphone owners. Working across five countries — Bangladesh, Côte d’Ivoire, Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa — we designed demographically representative panels of smartphone owners, and compensated them directly for sharing their data anonymously with us. The project website includes findings from all the workstreams, while an extension of the original work was supported by FSD Kenya and is available for download. Below, we’ll discuss some of these findings and what they mean for customers and providers in the markets we studied — and beyond.

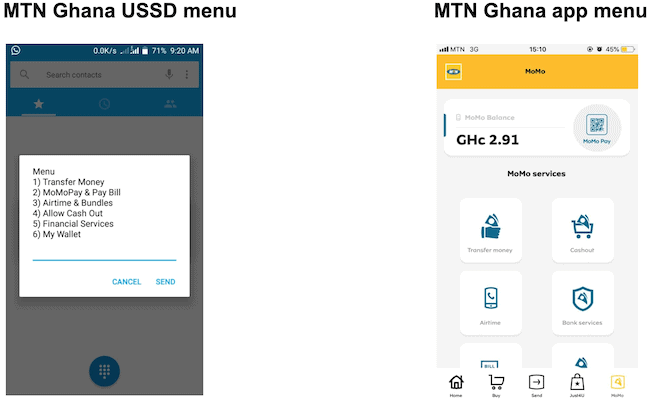

The Ongoing Popularity of USSD in Mobile Money

If you have a mobile money account, you’ve probably memorized the different USSD codes for sending and receiving payments, buying airtime, and more. As the original user interface for mobile money and mobile banking, dialing a shortcode — such as GT Bank’s famous *737# — to call up the USSD menu is muscle memory for hundreds of millions of people. Yes, smartphone apps can offer a much richer, more functional user experience. Yet anecdotally, we know that most people still use the USSD menu, which works on virtually any device. (Some providers, such as Safaricom/M-PESA, use SIM toolkit instead of USSD, which embeds the functionality in the SIM card instead of at the network layer; functionally the user experience is similar, and I use the term USSD to refer to both types.)

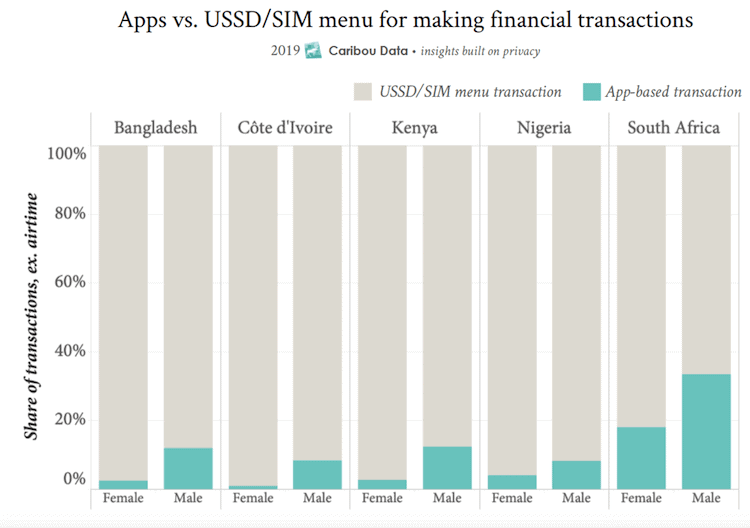

In order to quantify this preference for USSD, and determine whether there is a gender difference, we analyzed transaction data across all five countries in the study, and categorized each transaction (e.g., person-to-person payment, bill pay, bank transfer, etc.) as conducted via USSD or via a mobile app. Relevant mobile apps that we examined included the mobile network operators’ apps (e.g., MyMTN), dedicated fintech apps (e.g., Tala), and mobile banking apps from the major banks in each market. Even amongst our study participants, who were by definition smartphone users, 87% of all transactions were conducted via USSD, only 13% via mobile app. If you consider that smartphone penetration is probably between 25-40% in the countries in question, across the general population of mobile money users, we estimate that at least 94% of transactions are performed via USSD.

Fighting for 6%?

What, then, to make of the frothy market for consumer-facing fintechs in the Global South, with many millions of dollars in acquisitions and venture capital, when only 6% of transactions are being made using apps? Clearly, many of the big players have adopted USSD channels, likely out of necessity, to complement their mobile apps.

For example, Opay, Paga and Carbon all promote their sophisticated mobile apps, but they have each launched USSD alternatives for common transactions. Indeed, per Carbon CEO Chijioke Dozie, “One of the biggest selling points of USSD is that it works with or without the internet, which is reassuring in the African context where internet data is expensive and inconsistent. As fintech continues to develop across Africa, and ingrains itself into people’s everyday lives, it is important to invest and innovate across the ecosystem, ensuring that individuals are not excluded from the benefits of financial inclusion.”

Recognizing this need, platform-as-a-service (PaaS) startups such as Hover are providing fintechs with specialized services to support USSD initiatives. These services are useful because, while the USSD channel is near universal, utilizing it to build highly functional and easy-to-use interfaces — especially across markets and providers – isn’t easy.

Women don’t use financial apps

The chart below shows a clear gender difference in financial app behavior. In every market we studied, men were considerably more likely than women to use a mobile app instead of USSD to conduct transactions. This is an important finding, because due to the nature of the study population we essentially controlled for device ownership — i.e., the reason the women in the study didn’t use mobile apps to transact was not because they didn’t have a smartphone.

While the nature of our study did not allow us to ask qualitative questions, other work has shown that, broadly speaking, people use USSD over apps because of the former’s familiarity — which also builds trust — and the high price of data. That is, USSD sessions are free to the user and don’t require an internet connection, making them the default, “always-on” option that users can depend on.

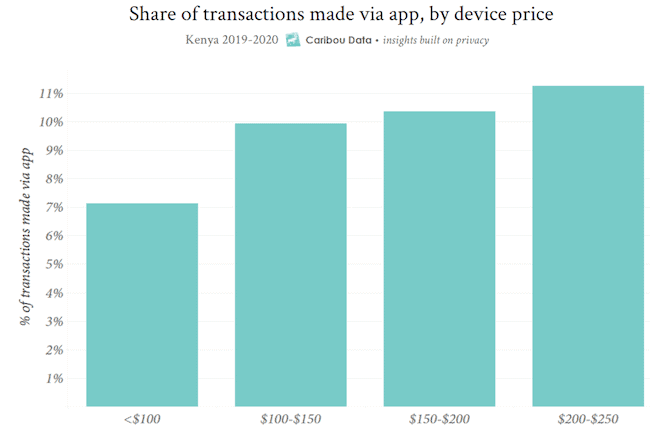

Other research has pointed to the inferior capabilities of low-end smartphones as constraints to more sophisticated digital usage — e.g., limited storage space forces users to uninstall apps before installing new ones, hindering adoption of new services. And of course poor touchscreen response, limited RAM and slow processors can make the user experience miserable. While we can’t disentangle all of the factors here, we did find that in Kenya, users with higher-priced devices were more likely to use apps to make transactions. (We determined price based on published retail sale prices for specific phone makes/models in each market, a reliable indicator of the relative difference in price between devices with different capabilities/performance.) The chart below shows that for the cheapest phones, those with a retail price of less than US $100, there is a significant decrease in the share of transactions made through a mobile app.

While we expect that many of these factors — especially the cost of data and higher levels of trust in USSD — play a role in the large discrepancy in financial app usage between men and women, we also assume an impact from well-documented structural gender inequalities. That is, recognizing that men are more likely to receive education, have income and access to cash, control household assets such as mobile phones, and enjoy the social acceptance of using mobile devices and the internet, we would expect a substantive difference in financial mobile app usage.

To the question posed at the beginning of this piece, these data suggest that at least in the near term, the smartphone era of internet-based transactions via mobile apps is more likely to exacerbate, not minimize, discrepancies in gendered adoption of financial services. This may seem counterintuitive, given the tremendously positive impact that mobile phones and mobile money have had on women’s access to financial services. But basic mobile phones and mobile money systems offered a fundamentally different ecosystem structure that mitigated many of the challenges limiting women’s participation in the formal financial sector. For instance, mobile money accounts are lower-cost to serve, they don’t require expensive bank branches in rural areas, they don’t require consumers to spend time and money to travel, and so on. The move from basic phones to smartphones, in contrast, offers comparatively few direct benefits for women that can’t be achieved with basic mobile phones and services.

This could change, however. As described above, the sensors and computing power of smartphones enable a wide range of use cases, including those not yet realized. It’s possible that in the future, a financial product might leverage smartphone functionality — say, biometric sensors — in a novel way that results in a direct positive impact on the gender gap, driving positive cycles of adoption and use of financial services.

One could argue that service providers such as Branch and Tala already use smartphones to do things that basic phones can’t: These digital lenders scrape data from their borrowers’ smartphones to inform their credit assessment algorithms — something that is indeed not possible with a basic or feature phone. These advantages might lead to greater smartphone app usage in digital lending. But the counterargument is that mobile money operators seem to be able to reach scale with USSD-based loan products just fine — as of December 2019, Safaricom and CBA’s M-Shwari loan/savings product had reached more than 31 million users, while M-Shwari saving account deposits had hit Sh18.7 billion.

In the meantime, service providers and policymakers would do well to recognize the biases that exist in mobile app usage, and to ensure that new financial services are accessible via USSD whenever possible. There is clearly a commercial incentive here, as many large fintechs have recognized the value in more broadly accessible services and have rolled out USSD alternatives. But there are also incentives for other actors, including handset vendors, mobile operators and network technology vendors, to promote smartphones as the standard interface for accessing digital products and services. If left unchecked, that development may have negative consequences for inclusive financial services.

Bryan Pon is an analyst and co-founder at Caribou Data.

Photo courtesy of Ketut Subiyanto.

- Categories

- Finance, Technology, Telecommunications, Transportation

- Tags

- data, financial inclusion, fintech