Four Ways to Support Vulnerable Youth: Key Takeaways from a Six-Year Livelihood Program

The current generation of 1.8 billion young people (aged 10-24) is the largest in our global history. This burgeoning youth cohort is especially evident in sub-Saharan Africa; the 10 youngest nations by population age are in sub-Saharan Africa; the median age in five of these countries—Niger, Uganda, Mali, Malawi and Zambia—is under 16 years, with approximately 60 percent of the population under the age of 25.

Harnessing this demographic dividend has proven difficult. Youth unemployment rates have remained persistently high for the last decade; working-age youth are three times as likely as adults to be unemployed. This issue is compounded for youth in rural African communities who have never been to school or who left school early. Gross school enrolment rates are some of the lowest for these youth, while their working poverty rates are some of the highest globally. The issue facing these young people is as much about underemployment and low-quality employment as it is about unemployment.

Launched in 2012, Youth in Action (YiA) was a six-year program implemented by Save the Children in partnership with the Mastercard Foundation. The goal of YiA was to improve the socioeconomic status of 40,000 out-of-school youth (12-18 years) in rural Burkina Faso, Egypt, Ethiopia, Malawi and Uganda. The YiA program aimed to strengthen work readiness skills, develop business and management capabilities, and create space for youth to apply these learned skills – all while supported by their families and community.

While there is a growing body of research on programming for youth livelihood development, the evidence on the effectiveness of these programs is mixed. Additionally, there are still questions around equity: Who benefits from these programs and who is left behind? To address some of these research gaps, Save the Children embedded 32 studies into the six years of implementing YiA. In October 2018, the organization launched a report—Supporting Rural Youth to Leverage Decent Work: Evidence from the Cross-Sectoral Youth in Action Program—that synthesizes the findings from the studies to reflect on four key evidence-based lessons.

Lesson 1: Work readiness is possible in four months

Since YiA focused on vulnerable, out-of-school youth, from rural communities in each of the five countries, the program prioritized supporting them to build functional literacy and numeracy, financial literacy and transferable life skills. YiA youth made significant and practical improvements in nearly all these work readiness skills in Burkina Faso, Egypt, Ethiopia and Uganda, but not in Malawi. (In Malawi we had higher than expected attrition in the sample and faced significant implementation problems.)

Literacy was one skill area where youth were still lagging after YiA: Less than half the youth in Burkina Faso, Egypt, Ethiopia and Malawi could read a third grade passage with comprehension by the end of the program. One of the issues was that, unlike other work readiness skills, youth had limited opportunities to practice their literacy foundations after the first four months of dedicated learning. They needed additional literacy instruction with more practical ways to practice their skills in the labor market. Overall, the findings support the YiA hypothesis that youth can build a wide variety of work readiness skills over a condensed time-period—four months of sessions, three sessions/week and three hours/day. This accelerated programming can be especially effective if coupled with focused and explicit instruction – as well as opportunities to engage in practical activities, like saving with a formal institution, that support future livelihood development.

Lesson 2: Livelihood development IS enhanced by family and community support

In the rural contexts where YiA was implemented, parents and community members are the gatekeepers to the labor market. Youth are developing their reputations in their community for being hard-working and responsible. One way in which youth can build this reputation is by participating in programs like YiA, providing a signal to family and community that they would make good employees, or that support for their youth-run businesses would pay off. YiA worked on this by engaging early with communities, and clearly explaining the program’s value in reliably supporting youth development. Prior to YiA, families and communities were hesitant to provide youth with substantial financial, material and/or emotional support for livelihood development. In all the countries, YiA youth reported marked increases in support from their families for livelihood development, in the form of space for a business, land, tools and/or emotional support. They also reported improved support from community business mentors at least nine months after graduating from the program. Additionally, increases in family and community support over the program period were associated with stronger gains in work readiness skills like financial literacy and communication.

Lesson 3: Quantitative data can mask gendered barriers

Disaggregating quantitative data by gender is the first step in measuring the impact of programs like YiA on males and females, as it points to any differences between youth of different genders. However, outcomes data may mask important gendered barriers that influence the livelihood development of male and female youth. For example, while male and female youth reported equivalent levels of and gains in family and community financial, emotional and material support in the outcomes data, the qualitative data highlighted that the kind of support often differed by gender. Families often provided female youth more limited financial resources than male youth, because female youth were viewed as having a smaller financial benefit for the family, since they would leave the home once married. Moreover, parents and community members often felt that the mobility of female youth had to be restricted to ensure their safety, resulting in more support for home-based microenterprises as compared to support for the wider range of non-home-based business options available for male youth. In some communities, this restriction on the type of microenterprise limited the income and savings opportunities for female youth.

Lesson 4: Rural Youth choose and can sustain self-employment

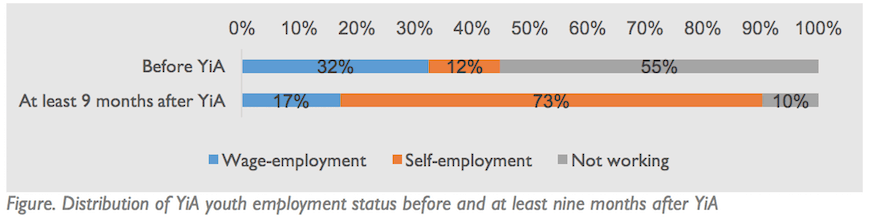

The figure below illustrates the employment status of youth before YiA and at least nine months after graduating (using pooled data for Burkina Faso, Egypt, Ethiopia and Uganda). We found a marked decrease in the percent of youth who were wage-employed and unemployed, and a statistically and practically significant increase in youth who were self-employed. This is likely because, while YiA offered five pathways for skills development, youth in all five countries overwhelmingly chose self-employment and started a micro-enterprise. The decrease in wage-employment may suggest less stability for some youth. However, wage employment before YiA was primarily seasonal and temporary. This is why YiA views the move to sustained self-employment as progress toward decent work for these young people.

While we were not able to disaggregate income and savings information based on which pathway youth selected, the fact that a majority of youth selected the self-employment pathway does suggest that improvements in income and savings are heavily influenced by the sustained self-employment of youth. In Egypt, Ethiopia and Uganda, youth were able to establish work that allowed them to individually move above the US$ 1.90/day international poverty line, effectively improving their socioeconomic status. Additionally, across Burkina Faso, Egypt, Ethiopia and Uganda, just 40 percent of youth reported saving formally or informally before YiA. At least nine months after YiA, this had increased to 80 percent of youth, with the average young person reporting an almost five-fold increase in the amount saved.

Next steps: Translating research to practice

This YiA research and learning was presented at a September 2018 research-practice forum—Evidence to Action: The Future of Work for Deprived Youth—hosted by Save the Children, with support from Accenture and in partnership with BRAC, the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab and the International Initiative for Impact Evaluation. The event identified and prioritized questions that remain unanswered about how, for whom, and in what context youth livelihood interventions are most successful. While programs like YiA have produced useful lessons that are being used by program designers, development practitioners still need to do a better job of translating research results into improved program design and implementation.

As we look to build more evidence on holistic skill-building models like YiA, future research should focus on more robust comparison-group studies that follow youth’s socioeconomic development from the start of the program to several years after it ends. Furthermore, the next round of research needs to move beyond simply disaggregating data by gender. We need to collect reliable and valid mixed methods data on gender norms among youth, in their families, and in their communities. Collecting gender norms data can provide us with a more dynamic understanding of the gendered barriers facing male and female youth, and how socioeconomic development varies based on the presence of specific norms. These research results need to be translated into explicit programmatic recommendations so that they are actionable for program designers and implementers.

Nikhit D’Sa is a developmental psychologist and principal investigator on studies related to Positive Youth Development (PYD), Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) and Education in Emergencies (EiE) at Save the Children.

Image courtesy of organization.

- Categories

- Education