What’s Next for Impact Investing : How to bridge the ‘Pioneer Gap’ and support entrepreneurs in the earliest stages

By mid 2011, Naveen Krishna, founder of SMV Wheels in Varanasi, India, employed 443 impoverished rickshaw pullers. Speaking with him then, one would not see any trace of the trials he endured two years earlier when he was burning through his savings and struggling to line up funds to launch SMV. He was not alone – entrepreneurs throughout the world struggle to find support for their ideas in the early years. Most run out of cash and have to scrap their ideas. Fortunately for Krishna, he received angel funding from his mentor, Sumit Swaroop, saving him from having to give up on SMV. By 2011, Krishna had refined his model and attracted $250,000 from five different impact investors.

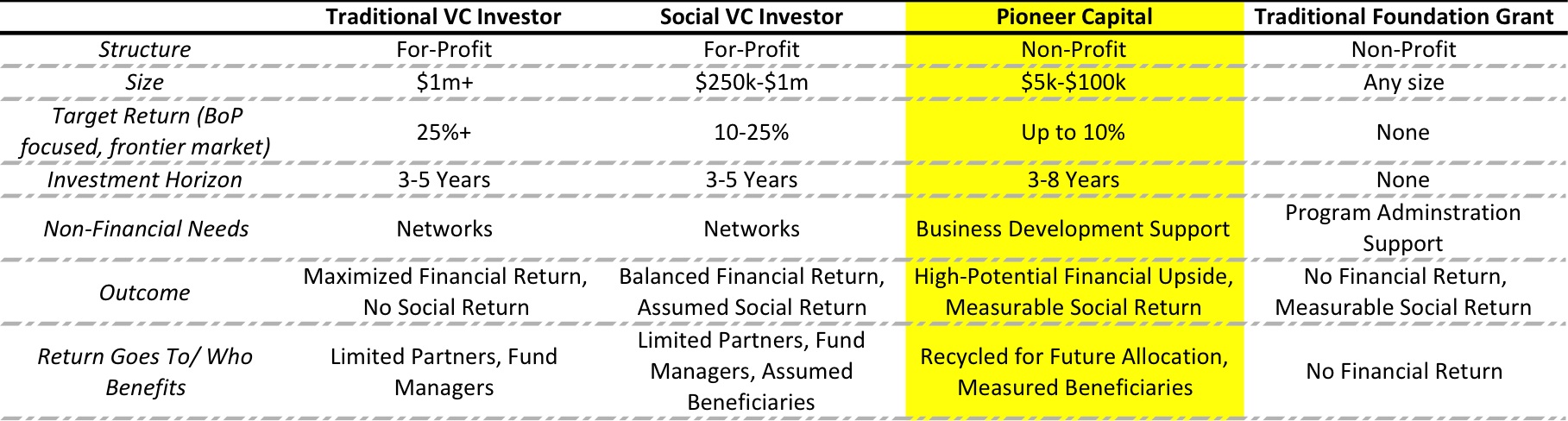

Announcements of impact-branded seed funds and investor networks have become so commonplace they no longer seem novel. It is heartening to see so much capital being deployed to these funds. However, the fact is most are structured to only invest in companies that are already succeeding and ready to scale. Their fund managers cannot afford not to reap a return, so it is extremely hard for these funds to take chances on novel ideas or unproven approaches. The resulting Pioneer Gap – best captured in the Monitor Group and Acumen Fund’s “From Blueprint to Scale” report – has been exposed, leaving many to ask what do we need to do to ensure that entrepreneurs like Krishna have the angel funding they need?

? Related: Monitor and Acumen Research Highlights Why Impact Investing Needs Philanthropy

Seeing the Need for Pioneer Capital

We founded Upaya Social Ventures with a mission to alleviate extreme poverty through job creation. We attack the Pioneer Gap head on by investing in early-stage (often unproven) concepts and empowering entrepreneurs like Krishna, who can be large-scale employers of the ultra poor.

In its earliest incarnation, Upaya was a for-profit concept, ready to harness social investment capital to realize its vision. However, even the most socially minded investors could not justify our uncertain return expectations with the high risk of funding startups rooted in extremely poor regions of North India. Nor were they willing to accept the overhead needed to provide hands-on business development support to entrepreneurs in the launch phase. These discussions reinforced for us the economic infeasibility of constructing a venture fund composed of small seed investments (less than $100,000) that can cover the costs of intensive technical assistance while producing a risk-appropriate financial return in a short amount of time.

We knew we needed to build a “safety valve” for the traditional venture model that would allow us to quickly back nascent but promising ideas and work alongside the entrepreneur to build the company. After extensive due diligence, we came to see philanthropic funds as the ideal capital to fill this role, ready to take chances in areas where return capital feared to tread. Furthermore, housing both the investing and technical assistance functions within a nonprofit – instead of splitting them through a hybrid model – opened access to foundations and donor agencies to more easily underwrite the needed business development support. Internally we called this strategy “Pioneer Capital,” and saw it as the best fit for our partners’ needs.

Like traditional grants, Pioneer Capital can provide the necessary cushion for entrepreneurs in the launch phase. However, unlike traditional grants, Pioneer Capital has a chance of producing financial upside for the investor. We at Upaya do believe that a handful of our investments will attain exits that yield decent returns, but those returns are exclusively restricted for reinvestment in future Upaya partners. Upaya’s goal is not to get rich off our investees, but to create a virtuous cycle of investment that can continually launch socially beneficial businesses.

Casting off the direct profit requirement freed the Upaya team to make small, catalytic investments into a dairy supply chain, silk weaving business, and domestic service training and placement firm for slum-dwellers. Alongside our seed funding, we have worked closely with these entrepreneurs and helped them assemble investor-ready business plans, financial statements, operational plans, HR procedures, and social metrics collection systems.

We have watched these businesses evolve from ideas scribbled on a dinner napkin into tangible operations that collectively employ more than 500 ultra-poor individuals, many earning a stable income for the first time. Furthermore, eager impact investors have approached each of our partners about possible investments as soon as they see a working unit model and feasible plan for scale.

What We’ve Learned Along the Way

There are countless others who are committed to catalyzing change in everything from clean energy to sanitation to health care that could benefit from our experience. We’ve learned plenty of lessons through our work and are happy to share them in the hope that they will help others fill the Pioneer Gap and create new impact investment opportunities in their areas of expertise. These lessons include:

Unique problems rarely have textbook solutions: As entrepreneurs experiment with their models, they need help from more experienced professionals. Some social business incubators provide technical support through required classroom-based training or off-site workshops. While they have value, this type of standardized instruction takes entrepreneurs out of the day-to-day management of their businesses and does not always equip them to adapt their models to their local realities. We find tremendous value in working with the entrepreneur on their turf, integrating the instruction into their reality. For example, when Upaya invested in Samridhi, a dairy company in Uttar Pradesh, it became clear that local cultural barriers made it hard for women to leave the home for several hours a day to work in a central dairy facility. Thus, it would be impossible to replicate dairy models that were successful in other geographies. By working alongside the entrepreneur in the field we were able to adapt the plan so that women could work from home. Without this onsite mentorship, we could not have helped the Samridhi team assemble a viable dairy model that, today, employs hundreds of local men and women.

Above: The son of a Samridhi employee milking a cow in front of the family home near Barabanki in Uttar Pradesh. (Image courtesy of Upaya Social Ventures)

Don’t make it a beauty pageant: Often the most effective solutions for a community don’t involve cutting-edge gadgetry or websites. Rather, expansion of commodity businesses, manufacturing, or service work may have a bigger impact – but investors must clearly understand their own goal to see the potential. This was the case with Upaya’s selection of Eco Kargha, a weaving company based in Bhagalpur, Bihar. Despite a centuries-old reputation for producing high quality silks, wools, and linens, the weaving industry in Bhagalpur was struggling to be a source of meaningful employment. The sole-proprietor and co-op based models that dominated the market lacked the sales and quality control capacity to take in and fill large domestic and international orders. Seeing an opportunity, Eco Kargha developed a concept that could market woven products, manage large wholesale orders, and in turn create steady, full-time employment in Bhagalpur. Of course, using wooden handloom technology to produce traditional sarees is hardly the type of “innovation” that captures the imagination of most social VCs. But because Upaya had oriented its selection process around a specific social goal – sustainable jobs – we backed a business with the potential to pay higher wages and make it possible for weaving to be a primary livelihood.

Above: Traditional wooden looms have passed down for generations by weaving families in the poor communities in and around Bhagalpur, Bihar. An Eco Kargha employee follows a traditional method for spinning bobbins by hand. (Image courtesy of Upaya Social Ventures)

Don’t try to hit a grand slam if nobody is on base: Too often impact investors – even those trying to focus on the seed stage – are enamored with massive outreach numbers and pass up businesses that don’t immediately appear “scaleable.” As the “From Blueprint to Scale” report made clear, there is a lot of hard work that precedes scale, and impact investors should not expect entrepreneurs to reach this point with one single swing of the bat. Instead, Upaya encourages all of its partners to first prove a financially viable unit model with a measurable level of social benefit before developing its scale plan. This approach can be seen in our partnership with Justrojgar, a company whose blend of training, placement, and employment support for service industry workers could help hundreds of thousands in the next few years. However, rather than trying to go for that scale immediately, we are working with the Justrojgar team to focus on one segment of its business – and only 50 pilot households – to refine its operational model and prove the unit economics. In turn, the company will be in a better position to showcase its social and financial potential to impact investors in successive funding rounds.

Looking Ahead

Impact investing is at an interesting crossroads. As Omidyar Network’s Matt Bannick and Paula Goldman articulated perfectly: “It is as if impact investors are lined up around the proverbial water pump waiting for the flood of deals, while no one is actually priming the pump!” If the goal is to encourage entrepreneurship and build a rich pipeline of novel solutions to age-old social problems, we must find creative strategies like the Pioneer Capital approach to give startups a better runway.

If we fall short, there’s no telling how entrepreneurs like Krishna will ever have the chance to make a difference.

- Categories

- Investing

- Tags

- impact investing