Turning Failure into Fuel: An Emerging Learning Platform Aims to Bring the Hidden Challenges in Humanitarian Energy to Light

Like most sectors, the humanitarian sector is eager to learn from success. But failure? It’s usually buried in reports or quietly brushed aside. Yet in humanitarian energy, where the risks are high, the needs urgent and funding is shrinking, we cannot afford to ignore it.

Access to clean, affordable energy in humanitarian settings is essential for safety, dignity and opportunity. But despite decades of pilot projects and interventions, refugees and other displaced people — who now number over 123 million globally — still face acute energy poverty. Diesel generators hum where solar grids could thrive, firewood burns where clean cookstoves are needed, and installed energy systems break down without proper operations and maintenance services to keep them running.

Meanwhile, the stakes are rising: With growing numbers of displacements, slow progress on energy access and tightening funding, we no longer have the luxury of time. And yet, the same mistakes keep being repeated across the sector, and our collective failure to learn from failure is undermining efforts to achieve sustainable energy for all.

In response, with the support of Innovation Norway and the Global Platform for Action on Sustainable Energy in Displacement Settings (GPA), we — a group of researchers and practitioners specialising in sustainable energy access across the globe — set out to answer two simple but overlooked questions: What’s going wrong in humanitarian energy access, and how can we systematically learn from it?

The Silent Drivers of Failure in Humanitarian Energy Projects

We examined 42 publications and conducted 20+ interviews with donors, implementers, energy providers and policymakers, sharing insights from this research in a new report: “Course Corrections: Improving Effectiveness and Efficiency in Humanitarian Energy.” Our aim was to understand the full spectrum of challenges facing energy projects in humanitarian settings, from subtle program pivots or narrowly missed targets, to more visible failures like project abandonments.

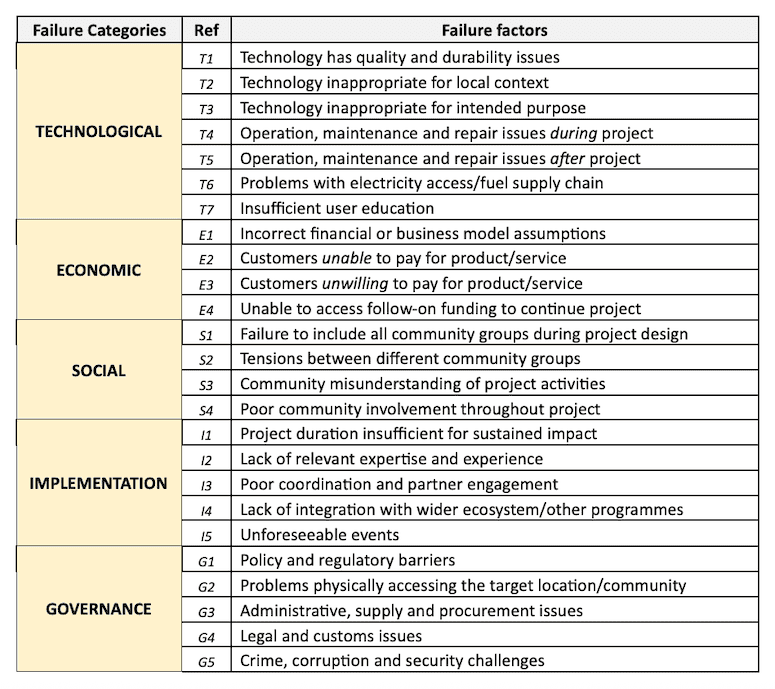

Table 1: Typologies of failures: different failure factors by category.

We uncovered five failure categories representing the most common barriers: economic, technological, social, governance-related and implementation-specific, each representing multiple factors (see Table 1 above, where each sub-failure factor is labeled with an alphanumeric reference code).

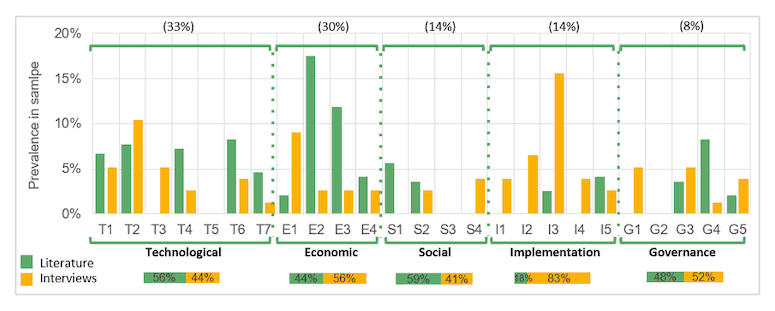

Figure 1 (below) shows the prevalence of these failure factors and categories, and how their reported occurrence varied when the experiential insights of designing, planning and implementing energy projects in humanitarian settings were obtained through a literature review versus through interviews with project stakeholders.

Figure 1: Failure factors and categories sourced from literature review and interviews.

Here’s what we found:

- Economic and technological issues dominate. Nearly two-thirds of all identified challenge factors fall into either the economic or technological categories.

- A few issues are overwhelmingly common, such as the inability or unwillingness of end-users to pay for energy services, the technical appropriateness of projects, and poor engagement and collaboration between partners. Just over half of the 25 failure factors appeared in more than 80% of the literature and interviews. These high-frequency issues are where sector-wide learning could have the greatest impact.

- One-third of challenges are institutional — i.e., governance and implementation-related. Governance issues, policy incoherence and bureaucratic hurdles were cited in 78 separate instances. These issues are less likely to be documented in reports but are no less damaging.

This assessment of failure factors also reveals something deeper: a disconnect between what’s documented in reports and what practitioners experience on the ground. For example, while the literature we reviewed emphasised economic and technical issues, the field experts we interviewed highlighted implementation barriers like fragmented coordination and short project timelines — challenges that rarely appear in formal evaluations.

This gap is part of the problem. If we don’t properly record the real reasons projects fall short, including the perspectives of the people tasked with implementing them, we won’t be able to fix them.

HELP: The Humanitarian Energy Learning Platform

To address this lack of systematic and transparent project documentation, we are currently developing the Humanitarian Energy Learning Platform (HELP): a centralised, inter-donor learning system, guided by insights from our interviews and literature review, designed to capture and share insights from past and ongoing energy projects in humanitarian settings.

Here’s how it works.

Practitioners working in the humanitarian energy sector, particularly implementors, will complete two standardised and highly specialised digital forms designed and tested via interviews with practitioners — one at project inception, and another at completion. These forms capture a project’s context, including its details and goals, as well as implementation challenges (and prospective challenges in the pre-project phase), outcomes (for the post-project forms), and direct contact points. The forms are designed to tease out aspects of projects that did not go to plan, thus documenting lessons learned and actively combating the positive reporting bias that is so rife in the development sector. Submissions will be stored in a searchable, access-controlled repository available only to organisations that are involved in offering energy services in humanitarian settings — and that are willing to contribute insights from their own projects via the learning forms, tagged by location, technology, challenge category or actor.

Ideally, practitioners will consult this knowledge bank of projects before project initiation, allowing them to learn from similar ongoing or past initiatives to proactively mitigate challenges. Periodic analysis of the repository data will also facilitate the learning process, with anonymised findings being shared via regular in-person events, reports and webinars.

Importantly, instead of acting as a monitoring or compliance tool, HELP will aim to provide a shared learning engine, one that treats success and failure as equally valuable inputs. By offering an open and facilitative learning space for practitioners, HELP will seek to prompt a shift against stigmatising failure, transforming it into productive lessons instead.

Our vision is for HELP to become a routine part of project cycles: Organisations will be able to leverage its data at the planning stage to see what has worked (or failed) in similar settings, and use the platform to conduct a structured reflection process at project close-out.

As part of the project with Innovation Norway and the GPA, we tested HELP on seven case studies — identified from scoping interviews and the literature review, and representing a diverse array of energy technologies, uses, end-users and humanitarian settings. Scaling these studies to hundreds would dramatically increase the platform’s utility. With enough uptake, HELP could generate the evidence base that energy practitioners working in humanitarian settings urgently need, paving the way for improved efficiency and effectiveness in humanitarian energy projects going forward.

Market-Based Solutions Need Shared Learning Too

Much of the humanitarian energy sector remains locked in the free-distribution model: Cookstoves, solar lanterns and solar home systems are handed out as aid, but they’re not maintained or embedded in sustainable delivery models. This leads to predictable breakdowns.

In contrast, market-based approaches — where refugees and host communities get access to energy services provided by the private sector, either at a market or subsidised rate — hold promise for longer-term sustainability. Yet making them work requires a deeper understanding of people’s capacity and willingness to pay, better demand forecasting, and stronger coordination between humanitarian actors and private sector providers.

The seven case studies used to pilot HELP underscore the complexity of this model. In one such study, 500 above-ground, container-based toilets were installed in Kakuma in a bid to address the dual challenge of inadequate sanitation facilities and poor access to cooking fuel. The faecal sludge served as raw material to make briquettes, offering both a clean cooking solution, and a way for refugees to make a living. But the project soon came to a halt, as it was revealed that briquettes could not hold a candle to the free firewood available to end-users. By the end, only 5% of the target briquette sales were reached.

The briquette case study could have benefited from insights on affordability, technology lifespan and implementation realities captured in a platform like HELP. But today, no such shared repository exists. HELP is being developed to fill this gap.

From the donor side, concerns often arise around the ethics of market-based models, especially when they target populations like displaced communities, which have limited means or legal rights to work. Some donors hesitate to support cost-recovery projects in refugee camps, fearing accusations of exploitation. But others are increasingly open to alternative financing mechanisms like carbon credits or results-based finance, recognising that humanitarian assistance must evolve as donation-based energy access cannot be sustained, particularly as the volume of need rises and humanitarian funding shrinks.

HELP will be uniquely positioned to support this shift by cataloguing where market-based models have worked, where they haven’t, and why. By capturing granular details, such as customer payment patterns, repair needs and cultural preferences, HELP will be able to inform product design and service delivery strategies. For instance, if multiple entries highlight low uptake of a clean cookstove due to its incompatibility with local cuisine, future designers can avoid the same error. If projects fail due to the inability to secure permits or partner with host governments, HELP can serve as an early warning and a practical guide.

A Cultural Shift Away from Siloed Knowledge

Currently, knowledge sits siloed within organisations: It gets buried in grant reports or lost with staff turnover. In practice, this means frontline staff often reinvent the wheel. Practitioners told us how simple missteps — like using solar lamps unsuited to local weather, hiring technicians who couldn’t access spare parts or promoting briquettes for cooking that were hard to light — went undocumented. These avoidable errors could have been prevented if organisations had a more accessible history of previous project decisions. HELP can empower implementers at every level to learn from peers working in similar environments, improving outcomes through shared operational wisdom.

Interviewees in our project were clear: We need more room for experimentation, a stronger mandate for adaptive learning and better mechanisms for capturing nuance. HELP aims to meet these needs. Whether it involves a donor revising funding guidelines to allow for greater flexibility or an implementing agency sharing lessons from a halted pilot, each insight shared on the platform will contribute to a more honest, responsive and effective sector.

It’s Time for Humanitarian Energy to Stop Hiding Failures

Humanitarian energy sits at a crossroads. Resources are contracting. Needs are expanding. And donors are under pressure to demonstrate impact. This is the moment to stop hiding failures and start harvesting them.

The project has made it clear that momentum is building among various humanitarian energy stakeholders — from public sector actors to private sector companies, and many others in between — to identify spaces and opportunities for knowledge sharing and learning from failures. Interviewees described growing interest in blended finance, service-based procurement models and better coordination. But scaling these approaches will require humility and honesty — traits that aren’t always associated with impact reporting in the humanitarian, and the wider development, sector.

HELP can act as a neutral, structured space for that honesty. Instead of assessing blame, the system will build collective intelligence. And with just a few hundred entries, HELP could begin to reveal patterns that no individual actor could identify alone. In the long-run, we hope that HELP will be integrated into sector-wide standards and funding requirements, so knowledge sharing becomes routine, not optional. As the sector moves toward more complex, multi-actor energy systems, the ability to see patterns across geography, time and approach will be invaluable.

Are you interested in contributing to HELP or accessing its early case studies? Get in touch with us at tash.perros.19@ucl.ac.uk and aimee.jenks@unitar.org. We’re actively inviting partners to join us in building a smarter humanitarian energy future.

Read the full report here: https://hip.innovationnorway.com/article/report-launch:-learning-from-failure-to-power-progress

Nazifa Rafa is a doctoral researcher studying Geography at the University of Cambridge; Tash Perros is a researcher and freelance consultant specialising in energy access in sub-Saharan Africa; Iwona Bisaga is Global Clean Cooking Lead at Norwegian Capacity and the Global Platform for Action on Sustainable Energy in Displacement Settings; Ronan Ferguson is a clean cooking consultant.

Photo credit: patpitchaya

- Categories

- Energy