Africa’s Tech Startup ‘Investment Frenzy’: Fact, Fantasy – or a Wakeup Call for Better Investing Strategies?

Editor’s Note: This article is a response to “Rethinking the ‘Africa Play’: Why We Held Back from the Africa Investment Frenzy,” a NextBillion article by Lauren Cochran, Managing Director at Blue Haven Initiative.

These are exciting times for African startups – and for their investors. The continent’s early-stage investment market is being driven by top talent from the African diaspora, returning home with global skills to solve African development challenges. Thanks to affordable mobile phones that provide platforms for payment apps, African innovators are launching digital solutions that the mobile industry association GSMA reports are “increasingly disrupting traditional value chains.” Their young companies are gaining traction in industries ranging from health care to agriculture – and they present an enticing opportunity for investors.

Unlike investors who witnessed this African startup venture momentum from afar, our LoftyInc team has participated in their growth for over a decade, establishing tech hubs, co-founding angel networks and building investment portfolios. Our Afropreneurs fund managers are now experienced impact entrepreneurs, startup investors and portfolio managers with a top-tier track record. Of course, some investees have failed, but others have attracted global partners and investors — including Visa, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, Greycroft and Al Gore’s Generation Investment Management. These portfolio winners drove the Afropreneurs Fund 1 portfolio to appreciate 19 times in nine years, and Fund 2 to appreciate three times within three years.

As one of LoftyInc’s Managing Partners, I’m often asked how we find local enterprises to support. The short answer is: through friendships with entrepreneurs among Africa’s returning diaspora. We have no problem with quality deal flow; we have shortlisted about 100 attractive ventures. That list grows daily, which is both encouraging and unfortunate: We’re inspired by the variety of investable ventures, but frustrated because our fund does not have enough capital under management to invest. Finding capital to grow West African startups led by local founders is our core challenge. We are regularly rebuffed by potential funders who rarely have personal experience as African entrepreneurs or as startup investors. Understandably, they prefer later-stage deals over startups – and ex-pat founders over local founders – a dynamic which contributes to a funding gap for African-led startups. This gap causes later-stage investors in Africa to perpetually complain of poor-quality deal flow, as it means African founders lack capital to grow their startups into later-stage companies.

Having lived with this reality for over 20 years, I was surprised by the recent NextBillion article by Lauren Cochran at Blue Haven Initiative, which cites a “capital glut” causing African startup valuations to explode, and warns that foreign investors may take their capital and go home. So, what is going on – is there too little capital for Africa’s startups, or suddenly too much?

The Problem: Excess of Capital, or Herd Mentality Among Investors?

Cochran’s article referenced data from the global VC firm Partech Partners, which celebrated the fact that “in 2018, 146 African start-ups raised a total of US $1.163 billion in equity through 164 rounds,” representing over 108% growth from the previous year. While that’s an impressive growth rate, Cochran stated it was “nearly 4 times more than in 2017,” when in fact the 4 times growth multiple cited by Partech happened over the prior 36 months, not year over year. In addition, 2018 was a record year for the global VC market overall – across all venture stages, not just African startups.

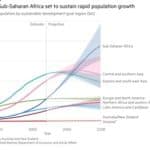

A more interesting question to ask is: How does that $1.16 billion invested into Africa’s tech startups in 2018 compare in a global context? That same year, India’s startups raised $10.6 billion, which represents almost $8 per person. U.S. startups raised $131 billion, which is roughly $400 per person. These data stand in stark contrast to Africa’s less than $1 per person in startup capital. So, even in a record year, Africa’s entrepreneurs had a dramatically lower level of VC investment to empower their startups, compared to other global markets. This lack of capital available for Africa’s startups would indicate relatively low valuations. So, why would American investors in Africa, like Blue Haven, complain of outsized startup valuations – unless they are looking at the same few deals made expensive by herd investing?

Indicators of group-think abound in Africa, where funding is unevenly distributed. Not only is most capital reserved for later stages, but a few countries get the lion’s share of it. Asoko Insight’s research on sub-Saharan Africa-based funds by size illustrates this point: Two-thirds of all Africa funds offices are located in just three countries – South Africa, Kenya and Nigeria. There are even major differences among these market-leading countries: In 2018, Kenya’s startups attracted more capital than Nigeria’s, despite Kenya having only one quarter of Nigeria’s population. Why do dramatic funding imbalances between similar nations exist?

It may boil down to investor familiarity (or lack thereof). “The vast majority of impact investment firms operating in Africa source funds from outside Africa and most make investment decisions outside Africa too,” says this World Economic Forum article, titled, “Impact investment favours expats over African entrepreneurs.” It cites local founders in Kenya who are angry that expat founders attract more capital than they do. A survey of 1079 co-founders across 788 startups, focused on Ghana, Kenya and Nigeria, quantified this dynamic. It found that Kenya “had the strongest presence of expat [foreign] co-founders of any single country,” and that, “In Kenya, 37% of the co-founders surveyed were expats compared to 10% in Ghana and 5% in Nigeria.”

People invest where and how they are most comfortable, so these numbers should not surprise us: Logically, the more recently a startup was launched, the less likely it is that a foreign investor would know about it – unless it was launched by an expat founder who comes from their homeland, or who is well-known in their expat community. Accordingly, the challenge facing foreign startup investors is less about a glut of capital driving a frenzy of investments, and more a matter of existing capital being invested inequitably across the continent.

How Should Investors Find and Value Startups in Africa?

This points toward one solution for foreign investors seeking startups at lower valuations: They could improve their connections to local startup ecosystems. Many hope to do so by launching their own tech accelerators, but such ecosystems take years to ripen into production lines of high-potential ventures. Alternatively, they could immediately leverage existing tech accelerators such as Wennovation Hub, which LoftyInc founders established in 2010. WeHubs are now located in four cities and have trained over 7,000 Nigerian entrepreneurs.

Since most capital gatekeepers are new to startup investing, they often carry over their enterprise valuation methods from their later-stage investing days. For example, later-stage investors may rely on the cash flow-based valuation system, which works well for asset-heavy companies that have been in business for decades. But it often undervalues asset-light ventures with rapid growth potential. Can a startup’s first few months of revenues predict future years of cash flows well enough to establish its current value? Emerging market innovators are often creating new markets: Can we value a market that does not yet exist? Spreadsheets may be a professional investor’s favorite tool, but they are more meaningful when enough data exists to populate them.

Experienced startup investors have developed other valuation methods, including: stage-based values, team composition, founder execution and product-market fit. These methods clearly favor investors who have local market expertise and background knowledge of local founder teams. They are most effective in the hands of investors with experience building African ventures themselves, who can advise African startup founders. When founders find such value-adding investors, they tell their peers, which drives more deal flow to those investors. Similarly, when founders have investors that impede their growth, they also share that news on the grapevine. One way or the other, the terms, strategies and capacity for value-addition that investors offer inevitably affect their deal flow.

A Lesson from Leading Startup Investors: Build Large Portfolios of Small Investments

For effective strategies, investors in Africa can look to the world’s most active startup investors, including 500 Startups (“500”) and Y Combinator (“YC”). These have accelerated some of LoftyInc’s African investees, and 500 co-taught our VC Unlocked Program with Stanford. Both have standardized vetting and investment processes, such as efficient S.A.F.E. financing documents, which investors like us use to save time and legal bills. Vetting focuses on founder team traits, such as following through on what they say they will do, and it is open to applicants from around the world. YC invests $150,000 for 7% of each venture. Applicants know what is on offer before they apply. Experienced mentors vet and accelerate batches of startups twice a year. They cast a wide net, to reduce the chance of missing out on winners. This strategy is consistent with Power-Law returns, as analyzed here by AngelList’s head of data science. As of August 2018, YC’s track record featured a portfolio of 1867 startups that had reached $100 billion in market value. Data comparisons with non-YC startups by year show that YC startups are 3 times more likely to become unicorns, and 4.5 times more likely to be valued at $100 million or more – and their batch quality is rising year-over-year.

Keiretsu Forum, which Pitchbook cites as 2018’s most active early-stage investor, has also shared lessons from its 20 years of startup investing via its 3,000-member network of angel investors. It too has fine-tuned collaborative selection, due diligence and terms processes. Its investment performance data is included in this white paper, which finds that large portfolios of at least 15 ventures per sector are more likely to hit angel returns of 20%+ IRR, and out-perform later-stage VC returns. Accordingly, Keiretsu now manages venture capital funds that help its members achieve these higher levels of portfolio diversification. The report concludes that its highest multiples are generated by due diligence teams with deep industry expertise, providing validation for experienced, indigenous fund managers and local founders.

For a decade, LoftyInc has deployed similar strategies when investing in African startups – and we’ve validated them with successful track records and robust deal pipelines. We invite other investors to join us – and to look past warnings that Africa’s startup ecosystem is already flush with investment dollars. On the contrary, there’s plenty of room for more capital – if you know where to look, and how to leverage it.

Marsha Wulff is a principal and Managing Partner of LoftyInc Capital Management.

Photo courtesy of CrizzlDizzl.

- Categories

- Investing