What’s Really Driving Africa’s ‘Investment Frenzy’?: An Entrepreneur Responds to Investor Concerns

Recently, Lauren Cochran, Managing Director at Blue Haven Initiative, wrote a thought-provoking article on NextBillion called “Rethinking the ‘Africa Play’: Why We Held Back from the Africa Investment Frenzy.” She made a compelling argument that the “growth-at-all-costs” approach to scaling is “an unsustainable concept” in Africa. Her rationale is sound:

- Tech-driven businesses in Africa require ongoing human engagement with customers that is hard to automate;

- Africa is fragmented across 54 countries that need to be cobbled together to get to an attractive addressable market;

- Growth equity and access to cheap debt are unreliable and scarce;

- The middle-class is still young; and

- There are a myriad of political and economic challenges for start-ups to overcome, such as trade barriers, currency risk, political instability, opaque tax regimes and heavy government debt burdens.

As I read the article, I found myself nodding my head most of the way through. Having recently ended my own 10-year journey building Zoona, one of Africa’s earliest fintechs, with a vision “to improve the financial health and well-being of one billion people” carved into a wooden plaque in our office lobby, I could relate to every challenge that Cochran highlighted (disclosure: Blue Haven is an investor in Zoona). Often, we faced several of these challenges at the same time, and ultimately had our unicorn ambitions chopped off at the knees with a $40 million growth equity round collapsing due to a lead investor changing their risk tolerance just as two telcos attacked us in Zambia by carpet bombing the market with copycat agent kiosks to grab our market share. Through the dedication and commitment of many, Zoona survived and managed to successfully launch a new fintech spinoff called Tilt, becoming a player in business-to-business payments. Meanwhile, I have spent the past several months writing a book about my journey as an entrepreneur in Africa, and reflecting on what I have learned and what might have been.

But while I agree with much of Cochran’s argument, her closing advice made me stop nodding:

“My advice? CEOs should adopt long-term thinking and seek out investors that acknowledge and understand reality, forget the ego-boost of big rounds and press releases, and double down on building businesses that work.”

As a general principle, I can’t find anything here to fault, and would advise any entrepreneur or CEO similarly. In fact, as I start a new entrepreneurial journey to build a new African fintech company, I intend to take this to heart. But from my perspective as an entrepreneur, this advice ignores a reality that many investors don’t recognize: What Cochran is asking not only goes against entrepreneurs’ core natures, it implies that entrepreneurs are in the power seat during the investment process, which is rarely the case.

What Entrepreneurship is All About

Professor Howard Stevenson, sometimes described as the “godfather of entrepreneurship studies” at Harvard Business School, defined entrepreneurship as “the pursuit of opportunity without regard to resources currently controlled.” This definition has always resonated with me, and it fits my observation of the other entrepreneurs I know best. It also reveals some of the underlying motivations of entrepreneurs, clarifying why we behave as we do.

The “pursuit” is about relentlessly battling through all of the adversity that makes building a company from an idea so hard and so addicting at the same time. If it was easy, everyone would do it, and I would have to go find a real job. Instead, I find myself called to action when I hear visionary entrepreneurs like Fred Swaniker advising us to use our privilege to “do hard things.” So yes, there are a host of challenges in Africa to overcome that rightfully have a place on any investor risk matrix. But I have learned that with perseverance, creativity, and sometimes a little luck, any and all of these challenges can be overcome. This is part of the job of being an entrepreneur anywhere, not just in Africa.

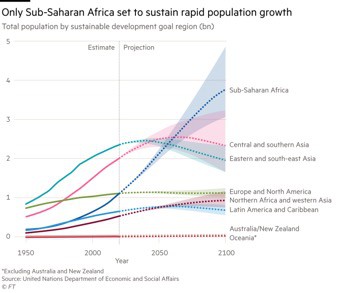

When it comes to defining the “opportunity” in Africa, I would argue that it is both enormous and urgent. About 1.3 billion people, or 17% of the world’s population, called Africa home in 2018. By 2050, these numbers are projected to rise to 2.5 billion and 25% respectively, with 50% of Africa’s population expected to be under 25 years old. There are already over 100 million informal micro and small enterprises in Africa, most of which are underserved – despite contributing to around 70% of the continent’s employment. In addition to the tremendous potential for impact, there is no doubt in my mind that there are many multi-billion dollar businesses waiting to be built to serve this growing need.

Billion dollar companies in Africa are not without precedent, despite a common misconception that there aren’t very many. In reality, there are more than 400, and they are faster-growing and more profitable than their global peers. Interswitch in Nigeria just became the first African fintech unicorn, and it would have gotten there faster if it wasn’t for a currency devaluation in 2016. Africa needs more of these success stories, not less, and they will be created by entrepreneurs who are bold enough to dream big – and who are relentless in their pursuit of big opportunities.

This brings us to the critical last part of Stevenson’s definition: “without regard to resources currently controlled.” Entrepreneurs typically suffer from overconfidence and positivity biases, which cause us to try to do too much with too little in the hope that we can secure more resources later. This increases risk and sometimes causes failure. And I’m guilty as charged. My failure to build Zoona into a purpose-driven billion dollar company is all the motivation I need to try again, and despite all conventional thinking and questioning to the contrary, I cannot bring myself to shrink my vision to anything less than massive scale – despite starting from scratch with zero financial resources at my disposal. And I’d be reluctant to advise other entrepreneurs to downsize the scale of their ambitions, because the world needs people who dream big.

That doesn’t mean entrepreneurs should be reckless or subscribe to wishful thinking. We can hone our instincts and improve our decision making with experience, and with the wisdom typically gained through failure. We can be more realistic in our planning and learn to build teams that cover our blind spots. But we can’t change who we are – and I don’t believe the world would be better off if we did. Instead, I think we need to shift the focus to that other key group of stakeholders, and to put the ball back in investors’ court.

Rethinking the Role of Investors in Africa

In my experience, the need to chase big investment rounds and big valuations is driven at least as much by investors as it is by entrepreneurs. A prime motivation for this is investors’ need to increase both their portfolio valuations and demonstrated exit multiples (which often occur through secondary sales in big rounds) to their limited partners within their standard 5-7 year exit windows. The “ego-boosting press releases” Cochran critiques are also created at least as much for investors, many of whom prioritize the names of the other investors on the cap table (for a sense of validation and safety in numbers) as much as the company and team they are investing in. Investors are also typically in fundraising mode themselves, and have an equal incentive to hype up press releases about funding rounds. Likewise, the big valuations she criticizes are generally set by investors, as a function of supply and demand: Entrepreneurs often get buried beneath stacks of liquidation preferences that provide us with no downside protection, and incentivize us to think and act big to have any chance of making money.

As an entrepreneur raising capital, I have to be positive, confident, and tell a growth story that excites investors enough to pursue me. If I don’t do this, others will – and they will get the capital to build their vision, while I will be stuck with too little to build mine. Because venture capital in Africa at most stages is scarce, and institutional investors typically move slowly and wait for sufficient validation and de-risking to occur before investing, I have to scour the globe for money where I can get it. Every entrepreneur I know has to do this, and no entrepreneur I know enjoys it, or wouldn’t rather be focused on building their business instead. And for those lucky enough to close an investment round, they deserve that press release – and it’s not a matter of ego: It is incredibly hard to reach that milestone (and it is also necessary to attract talent and get on the radar of other investors for the next round).

I agree with Cochran that it would be a lot easier if entrepreneurs could short-circuit this process by focusing only on the most knowledgeable investors who “get Africa” and back long-term thinking. But few of us have this luxury – we have to chase the money where we can get it. Instead, investors need to meet entrepreneurs halfway and appreciate that their core role is to supply entrepreneurs with the capital we need to make our visions reality, rather than act as the demand we should chase for validation. They also need to recognize that, because of all the challenges and the early-stage state of most ecosystems, start-ups in Africa don’t often mature at the pace that investors necessarily require or desire. The typical 5-7 year venture capital exit window should be shifted to 8-10, because that’s frankly how long it takes. In addition, much more risk-tolerant growth capital needs to come to the party, so that the most promising companies don’t have to lose momentum or sell short just when they are hitting their stride.

In closing, I offer the following modified advice to build on Cochran’s original sentiment: Investors should proactively seek out and back entrepreneurs with long-term thinking and positive unit economics, support us as much as possible to navigate the many obstacles in front of us – and most importantly, help us get the patient and risk-tolerant capital we need, so that we can double down on building big businesses that work to improve the lives of others.

Mike Quinn is the co-founder and former Group CEO of Zoona. His personal website is https://www.mikequinn.co/.

Photo courtesy of World Relief Spokane.

- Categories

- Finance, Investing, Social Enterprise