As Impact Investors We Often Miss One Thing: Who Has the Power?

Capability of founder(s) + strength of product + $$ potential = Potential of an enterprise.

Sharp investors look at these basic qualities to assess the potential of an investment. But these factors address only half of the equation for impact investors who look for a financial return and impact. Rather than solving for the other half, impact investors tend to dig deeper into the same equation while trying to sniff out impact – asking things like: How sustainably is the product or service manufactured? Who/what is impacted by that process? Who are the customers and can they afford the product?

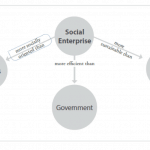

These are fair questions that may help test the probability of impact, but they fail to get at the fundamental differentiator between a traditional investor and an impact investor: How does the enterprise localize power?

The essential question

The horrors of colonialization perpetuate because this question was given only lip service. Urban housing projects have failed because this was not fully appreciated. Development aid often miscarries because this question is not prioritized. Impact investing will likely backfire if this question is not kept front and center.

Lasting impact is about empowerment of people. A company cannot be a lasting-impact social enterprise purely on the basis of the nature of a product or service it is providing, because of the poverty level of the consumer choosing the product, or because of the staying-power (profitability) of the enterprise itself. The business model of an enterprise must fundamentally localize power to the target market/beneficiaries.

The urgency of basic needs can obscure root issues related to empowerment, and subconscious patronizing can sometimes undermine the best of our good intentions. Rather than devoting the full abundance of resources to urgently address massive empowerment deficits like poverty and lack of education, significant resources get cannibalized by the allure of must-have-now “life-saving” products. As funders, we need the humility to recognize that we cannot even know which life-saving products should be prioritized (and how) until there is first a shift in the locus of power. Most needs will organically be served by rebalancing the locus of power so that local actors and the local market are free to decide how they want to spend their resources and how they will best be served.

Impact should be determined primarily by how needs are addressed, and that determination should be made by the primary agents and target consumers themselves. Things like better nutrition, or cleaner power, or better farm yields are all critical priorities and at the foundation of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. But they do not provide a substantively different impact on someone’s empowerment than, say, the internet, a car, or financial advisory services. The internet provides access to information, a car provides mobility and financial advisory services (should) provide increased income. Meeting basic needs is, of course, more urgent than a new car – but the basic needs exist because of the underlying deficit of mass empowerment. For a product to have more than a fleeting impact, the business model must prioritize and share decision-making equity with both employees and end users.

the Value of Power

The value of power is greatest to those with the least of it and most overlooked by those with most of it. History shows civilizations willing to sacrifice everything for the freedom (empowerment) to determine their own choices over food, shelter and even the smallest aspects of their lives. Disempowered people are often willing to die fighting for their right to determine their own destinies. Tapping into this desire for empowerment is the key to scaling an enterprise without diluting impact, on account of an ever-growing distance between the leading edge of business activity and a centralized locus of power.

Take the example of a profitable social enterprise selling an affordable clean cookstove to a single, poor Congolese mother. To assess if the locus of power is being localized, we have to look beyond how much the stove reduces smoke, how much charcoal it saves, how “sustainable” the enterprise is, and how “affordable” the stove is. Assessing the product-market fit and profitability of the business only scratches the surface. We need to ask questions like: How does the business model decrease the mother’s dependency on the company and increase her financial independence? How does it promote her community’s financial independence? How does the clean stove business model empower its employees? Where is the greatest benefit being derived via the business activity – and is that benefit being fairly distributed among all players? Is a fair amount of the income derived from the business activity being reinvested into the local economy?

A profitable company selling an improved cookstove to an impoverished woman could have minimal impact. Sure, the company is sustainable and the woman is marginally happier and healthier, but how is the business model shifting the locus of power to the local community to lift the community out of poverty? What if the Congolese mother said: “Give me the dirty old cookstove for half the price and give me the other half to do with what I want?” All of this is to say: If given the opportunity of financial freedom or having cleaner air in her home – what would the mother choose? This is not just a theoretical question – it is a question marginalized groups have answered many times. They have answered how every human does: “Empower us.”

Dreaming Bigger

Impact should be evaluated by how the business model provides opportunity for empowerment. Not only by which consumer segment is served – by how the consumer segment is empowered. Not only by uniqueness of a product – by how the production, distribution and use of the product empowers the local community. Not only by profitability of the enterprise – by how equitably financial gains are distributed among investors, employees and communities. Lasting impact cannot happen without empowering local partners and consumers to fundamentally own their own priorities and decisions. Shifting the locus of power means treating employees and consumers as people with dreams as big as yours.

“It is the nature of [humans] to rise to greatness if greatness is expected of [them].” – John Steinbeck

Editor’s Note: This article was voted by readers as one of NextBillion’s Most Influential Articles of 2018.

Galen Welsch is the co-founder of Jibu.

Photo by Stevepb via Pixabay