Client Outcomes Data in Microfinance: Few Have It But Everybody Needs It

The promise of microfinance is that it can create positive effects in the lives of clients. Certainly, that hope is reflected in the mission statements of financial service providers (FSPs) that offer their products to the vulnerable and the poor, and in the way that social impact investors describe their work. Yet, by and large, stakeholders in the microfinance sector have functioned for the past many decades on hopes and assumptions, and even the most sincere stakeholders have tended to use output data (e.g., how many people used a service) as a proxy for outcome data (e.g., how many people benefited from that service). More recently, many independent research studies have found no or minimal average positive impact by microfinance on clients’ lives. This has generated a considerable amount of reflection and debate: Does microfinance not work? Does it work but our claims are exaggerated? Are the studies flawed in their design? Are the results correct but the interpretation wrong? Most of all: What do we do next?

Social Performance Task Force (SPTF) members have put a lot of thought into the following three complementary questions:

- What outcomes are clients actually experiencing?

- What can we do to improve outcomes for clients?

- Are client outcomes data relevant to all financial service providers, or only to those with social missions?

Logic tells us we cannot fully answer any of these questions without having client outcomes data. So why don’t more FSPs collect it?

The SPTF Outcomes Working Group (OWG) spent the past year attacking this problem. We found a significant lack of institutional buy-in. We heard again and again that collecting outcomes data is too expensive, not a priority and no one has the time to do it. But we also heard from the few FSPs that do collect outcomes data that it is worth the effort, it can be affordable, that it is certainly a priority and existing staff can do it. From this research, OWG facilitator Frances Sinha wrote a document that makes the case for outcomes management and a document for FSPs that explains how to create an outcomes management system that provides credible and relevant information in an affordable way.

SPTF also collaborated with the e-MFP Social Performance Outcomes Action Group on the development of guidelines for investors on outcomes management, which was written by Lucia Spaggiari with extensive input from investors. Additionally, each of the new resources contains an annex with a short list of recommended outcome indicators developed by SPTF sub-working groups in four principal outcome areas: poverty, business, resilience and health (these were contributed by Freedom from Hunger).

The making-the-case brief argues that outcomes data are relevant to any responsible financial service provider, meaning even those without an explicit social mission. Sinha classified the reasons why outcomes data are relevant into four main categories: i) to be accountable; ii) to review what is working; iii) to improve outcomes for clients; and iv) to strengthen the institution’s business.

Among the many specific examples she cites are these:

- CRECER (Bolivia) research on its Credit with Education program did not show positive results on nutrition-related health behaviors of mothers and the nutritional status of their children. But when the results were disaggregated by the estimated quality of the education provided by the field agent on health and nutrition, the clients who had received high quality education did show positive results. This sent a clear message that the program could be effective, but CRECER needed to improve the quality of the education provided by some of its field agents. CRECER then reorganized how it implemented field agent training and supervision.

- An AMK (Cambodia) study on the well-being of clients identified an increasing number of clients reporting that they faced a crisis in the previous year, and fewer reporting that they never borrowed or sold assets to pay for medical care or medicine. These disappointing findings highlighted the significance of health care challenges for poor households. With the board’s approval, AMK explored the market and ultimately started a health insurance program. This led to better results for clients both in health and in their ability to use their microfinance loans productively.

- IDEPRO (Bolivia) offers loan plus business development services tailored to the sector in which the client operates. By monitoring outcomes on key business indicators over time, with analysis segmented by the sector in which the client worked, IDEPRO learned that clients generally were achieving good results in all sectors except tourism. Management therefore ceased to target clients operating in the tourism sector.

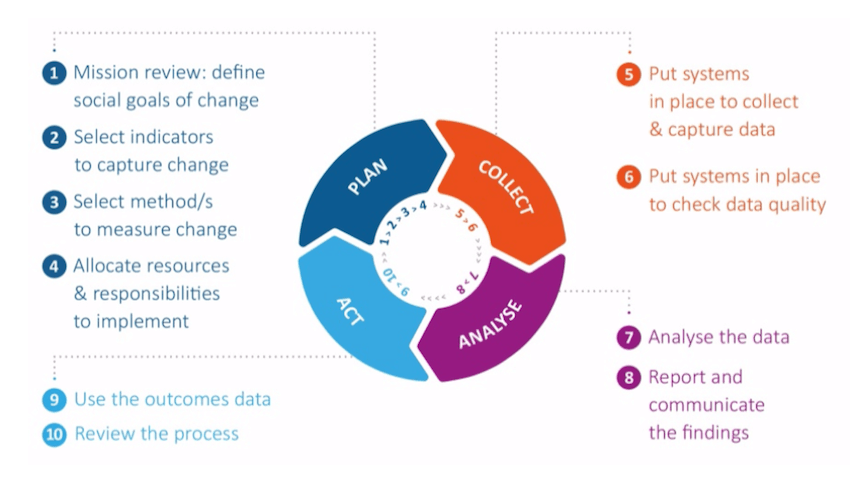

Outcomes management is a complete system. Though the system does not have to be terribly expensive, it does require some investment and it must include more than simple data collection. Specifically, data have to be collected, verified, analyzed and reported to management if they are to be useful. The graphic below summarizes the 10 main steps in outcomes management:

Building on the work done last year, OWG has begun pilot tests in Peru and in India:

- Peru: Bobbi Gray of Grameen Foundation, with assistance from independent consultant Norma Rosas Lizárraga, is leading a pilot test with three different financial service providers: PRISMA, Norandino and FINCA Peru. To begin, each institution is clarifying its theory of change, reviewing the list of recommended outcome indicators, and selecting a few indicators to monitor. Lizárraga is also conducting focus group discussions with clients to learn which outcomes they are hoping to achieve as a result of their use of microfinance products and services. Next, all three institutions will create internal systems for outcomes management, with a particular emphasis on using the data to inform management decisions. They will then do at least two rounds of data collection. The pilot work is preliminarily scheduled to last three years. SPTF will share learning with the broader OWG throughout the process.

- India: With funding from SIDBI and DFID, Devahuti Choudhury of Grameen Foundation India (GFI) is currently leading two projects related to the collection, analysis and use of outcomes data, and is collaborating with SPTF to integrate some of the recommended outcomes indicators into each project. The first project involves implementing a comprehensive survey on outcomes with 20 different FSPs in India of varying sizes, legal structures and levels of engagement with social performance management. The second project will involve extended and more intensive work with four of the FSPs participating in the outcomes data survey, each of which will develop an internal system to embed outcomes management into its ongoing operations. GFI and SPTF will work jointly to document learning from the field and facilitate peer exchange among the participating institutions.

The pilot testing is new, but some interesting insights are already emerging from the exercises of defining each institution’s theory. From previous projects in this area, we know that one common pitfall is for an institution to have a theory of change that is too vague, such as the common “We seek to improve clients’ lives.” A first step is to answer the question, “Improve lives in what way, specifically?” But this current round of pilot testing, particularly coupled with reflections on how to interpret findings from recent impact studies, is highlighting the importance of two additional considerations:

- Are you certain you have chosen the indicator that matches your exact theory of change? For example, if the facet in clients’ lives that you want to improve is poverty alleviation, any number of indicators will fall within that theme. You could select annual growth in household income. You could track average monthly balance in a savings account. You could monitor improvements in housing. You could monitor stability of income. In short, you need to be very careful to select an indicator that answers the right question and provides you with data that are actionable by your institution.

- Are you monitoring whether clients are worse off? Generally speaking, if an FSP segments its analysis as opposed to measuring average change for its entire client base, it will observe that some clients are better off, some are about the same, and some are worse off. The question arises, if most clients are doing better, is that good enough? Or does the FSP have a responsibility to understand who is experiencing negative outcomes, what is driving them and how to minimize them? One potential solution would be for an FSP to include in its theory of change discussion, and subsequent choice of which indicators to track, not only the indicators that would show positive effects, but also at least one that would detect early signs of client stress. SPTF is currently working with Bobbi Gray and independent consultant Anton Simanowitz to further our understanding of client stress indicators.

As always, SPTF invites you to share your experience and join the discussion: info@sptf.info.

Amelia Greenberg is the deputy director of the Social Performance Task Force.

Photo: An entrepreneur in the Karongi region of Rwanda who opened her own store – and increased her household income – thanks to microfinance loans from an MFI called Inkunga. Photo by Amelia Greenberg

- Categories

- Uncategorized