India’s Demographic Dividend: The Impact Opportunity in Student-Led Social Business

What is the most effective way to create a social impact: running one large social business catering to 100,000 people, or 100 small social businesses catering to 1,000 people each?

That’s a key question facing the sector in India, where the social enterprise ecosystem is growing at a very rapid pace. Countless new enterprises have been founded in the past decade, and many traditional businesses have transformed themselves into social businesses by adopting more ethical and sustainable principles. Yet the country’s overall startup ecosystem, despite being one of the most robust in the world, doesn’t support social enterprises as much it does “commercial” enterprises. And the support it does offer tends to be directed toward larger, more established businesses.

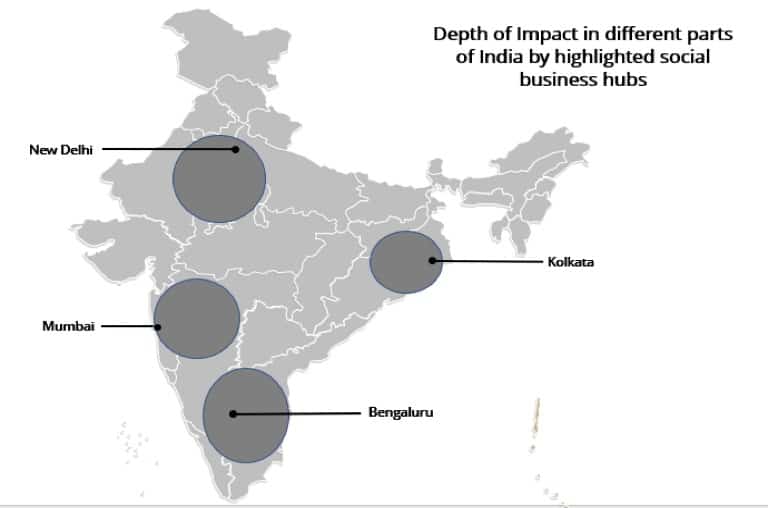

This lack of financial support is illustrated by the fact that only $1.6 billion was invested in 220 social enterprises between 2000 and 2014, with 60% of that funding going to just 15 investees (according to a 2014 Intellecap report). This dynamic reflects trends in commercial startup investing, where unicorn rounds of investment are increasingly common in India – from OYO Rooms to Ola Cabs, Swiggy and many more like them. Further, although the entry of big private equity players such as TPG Capital and the Carlyle Group in the Indian impact ecosystem is a positive sign, they do not tend to invest in businesses in the early stages, when their support is most needed. What’s more, around 55% of the country’s social enterprises are headquartered in just nine cities, and this geographic imbalance has been increasing.

Due to this inadequate funding, many social enterprises end up relying upon short-term institutional projects and grants to stay in business. But this is not enough: With an estimated two million social enterprises in India, those that are unable to raise grants or patient early-stage investments often perish, or are forced to deviate from their social objectives. As a result, India still lags far behind other countries in terms of social enterprise growth indicators like funding raised, series stage reached, geographic expansion and number of lives directly impacted.

What can be done to turn this situation around? Clearly, one solution would involve a massive influx of patient capital for social enterprises of all sizes. But that seems unlikely, at least in the near term – and it’s not the only way forward.

One Solution: Empowering Student Entrepreneurs

Based on our research, there are three kinds of social businesses that have shown a major growth trajectory in India. These include:

- Businesses with a price differential/cross-subsidized model, in which a social enterprise sells different products at different prices to different customers, based on their economic background and ability to pay (eg: Aravind Eye Care)

- Businesses run by poor people, including social enterprises either founded by poor people or featuring poor people as promoters, suppliers and/or customers (eg: RangSutra Crafts, Grameen Bank in Bangladesh)

- Startups with heavy cash cushions, including social enterprises built by large trusts and corporations, catering to specific social and environmental needs (eg: social businesses started by Tata Trusts, Azim Premji Foundation and other organizations)

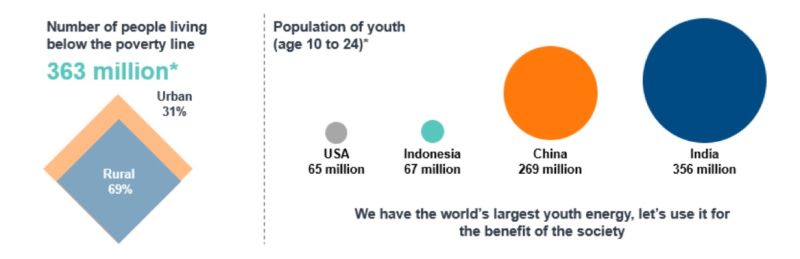

But these are not the only paths to social business success. India is blessed with a demographic dividend, and it has the largest youth population in the world. To maximize the social sector’s impact, we believe that India needs to leverage this youth energy to build multiple small social businesses run by young entrepreneurs, through a model called student-led social business (SLSB).

Demographics of India. Source – Social Entrepreneurship in India by Swissnex India

An SLSB is a small social business started by the students of an academic institution, with or without the formal support of that institution, with the goal of impacting the community around them. Other than the fact that it’s started by students, this type of business is no different from a traditional social business with a mission to create impact. Let’s explore the kind of impact these enterprises can make, through the example of an SLSB we started in a small Indian town.

Social Impact for $36: The story of Saksham

In 2013 we worked with fellow students at our college to start Saksham in Pilani, Rajasthan, with the goal of helping two high school girls cover their educational expenses. Though it’s a small hamlet, Pilani is widely known for its quality educational institutes, including the Birla Institute of Technology and Science, and its large student population. These students need notebooks throughout the school year, and they produce waste paper at the end of it. This means there was an opportunity to create a circular economy: We decided to tap into it by equipping the girls in the local community to create notebooks out of the waste paper generated by students.

In rural areas in India, social enterprises face prevalent social taboos – and so did we. For instance, the girls we worked with were not allowed to step outside their houses to work. Therefore, we had to figure out a way to deal with these social constraints, and also to help the girls financially.

To provide the supply of paper to the girls’ homes, we partnered with a student-run NGO which transferred the waste paper supplies to the village head, from whom a male member of the girls’ families could collect them and hand them over to the girls. For other consumables required to make notebooks, we decided to invest our own pocket money, with which we bought stationery worth INR 2500 (US $36). To collect waste paper, initially we collaborated with a different student-run NGO that conducted regular waste paper collection drives, but later we encouraged the families of the girls to collect it themselves. Meanwhile, we also partnered with local recyclers to ensure a constant supply of paper, in case the quality of the waste paper collected was too poor to be directly re-usable. The recyclers gave us good quality paper in exchange for poor quality paper suitable for recycling, at a premium. In our first cycle, we were able to collect 100 kg (220 lbs) of waste paper and create 60 notebooks out of it.

To sell these notebooks, we partnered with different NGOs which sold them at various community and fundraising events. In the first drive, we sold all the 60 notebooks at a price of INR 50 (US $0.80) each, generating enough revenue to cover our expenditure and working capital needs. The profits from the business were distributed proportionately to the girls. Though the income generated was modest, it was enough to prove the concept and encourage us to continue with the enterprise. The next step was to grow the business and achieve better profits and income for the girls. We conducted multiple drives for two more years, and the number of working girls increased from two to eight, ultimately providing an income of up to INR 3000 (US $42) per month for each of them. This might not seem like a significant amount, but in those years (2013-14), this additional income was a source of great relief to the families. It also helped those girls improve their social status, especially at a time when their families likely viewed them as a cost burden.

Along with working for the business, the girls also participated in various capacity development programmes organized by us. The aim of the initiative was to eventually make Saksham self-sustainable without any kind of involvement from our side. But though the business worked well for three years, it could not survive after that because the barriers the girls were facing were too much for them to manage the business on their own.

The experience taught us a lot, however. We realized that this kind of social business should have a governing body to guide it and a strong management team to lead it. We actually took both these roles while we were a part of it, and it taught us a great deal about the challenges of running a business. Saksham also showed us how a small amount of money (an initial investment of just US $36) could make a real impact on people’s lives. Learning from our experience, we believe the model behind this sort of small SLSB could make an even more substantial impact on India’s social business sector.

Why SLSBs could be a solution

SLSBs can be highly beneficial for the Indian social business ecosystem for a variety of reasons. For instance, they:

- Give students first-hand experience of entrepreneurship, thus creating social entrepreneurs right from within educational institutes.

- Leverage the power and reach of universities, which can take a variety of roles in a business – from accelerator, incubator or investor, to board member or mentor. Universities’ pan-India presence can help create social enterprises in low-tier geographies, leading to a deepening of impact beyond major population centers.

- Face less pressure to generate monetary returns, as university-supported social enterprises do not need to provide an income for the student entrepreneur or returns for outside investors, and profits can be reinvested entirely in the business, and used to benefit the community members who participate in it.

- Are able to use their proximity to educational institutions to facilitate innovation and research, which is currently lacking in social enterprises.

In spite of this potential, the SLSB model is largely unknown in India. To our knowledge, no university has formally embraced the concept – though there are Indian universities that run courses on social entrepreneurship, and two of them have impact incubators which are open to outside enterprises. Even outside of India, the concept of student-led social impact initiatives is still nascent – but the idea is starting to attract attention. In the U.S., for instance, the University of Michigan is partnering with the William Davidson Institute (note: WDI is NextBillion’s parent organization) to establish a curriculum-based, student-run international investment fund that’s believed to be the first of its kind at a U.S. university. The fund will target small- and medium-sized enterprises in India.

If the SLSB model could penetrate even 10% (~4000) of India’s colleges and universities, we could potentially create more than 20,000 social entrepreneurs, based on the estimate of five social entrepreneurs per educational institute. If each enterprise employs even five people, this could give direct employment to 100,000 people and, with an average of around five people per household in India, potentially create a deeper impact on around half a million lives. And this impact would only grow, as more educational institutions got involved. What’s more, many of the enterprises created would likely gain enough traction to become self-sustaining, continuing to deliver benefits even after the student entrepreneurs who founded them had finished their education. And many of these entrepreneurs would likely opt to dedicate themselves to growing these successful businesses (or starting others), even after graduating.

Call to action

For universities, setting up SLSBs could be a good first step towards the larger goal of establishing impact incubators, of which there are almost none in India today. With a growing supply of mentoring as well as financial support from investors focused on the country, there is a demand for more sustainable and impactful social and environmental projects. Universities and other youth-focused organizations can tap into this opportunity. India is blessed with a great amount of intellectual capital and youth energy: Now is the time to use it to make a difference.

If the idea of student-led social business interests you, please feel free to email us at geet.kalra@yunussb.com.

Our sincere thanks to Suresh K. Krishna and Priya Shah at Yunus Social Business, and Praniti Maini at Haas school of Business (UC Berkeley), all great social entrepreneurs and even greater human beings, for their constant support and guidance in refining this model.

Geet Kalra is a Portfolio Associate at Yunus Social Business and also Director of the Social Business Youth Alliance in India.

Nandan Luthra is an advisory analyst with Novartis.

Photo courtesy of Megapixl.

- Categories

- Social Enterprise