Is Latin America and the Caribbean Really Just 1% Circular?: A New Report Highlights the Hidden Role of Informal Workers in the Circular Economy

Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) is 1% circular — far below the global average of 7.2%. This means that of all the materials flowing through the region’s economy, less than 1% re-enter the economy for a second life through repair, reuse, recycling or other means.

This rather alarming number is a key finding of the “Circularity Gap Report Latin America and the Caribbean,” which we at Circle Economy Foundation recently released. It marks the first time we’ve applied our trademark Circularity Metric — launched at a global level in 2018 and later applied to several countries — to a specific region. But although the Circularity Metric represents our attempt to make progress toward circularity easier to grasp by measuring it with a single figure, in regions like LAC, the reality is considerably more nuanced than the number.

Although official statistics benchmark circularity at less than 1%, the region is home to a bustling informal economy — a network of street vendors, waste pickers, unregistered businesses and more, totalling 130 million workers and representing around 60% of the workforce. This level of informality means that there’s a range of “hidden” activities that could impact the region’s circularity, as well as unknown material and carbon footprints.

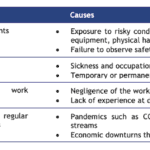

Informal jobs lack official employment contracts or registration, meaning access to social protection is sparse and labour rights can go unrespected — but they’re also a global norm, employing an estimated 2 billion people worldwide. In some sectors and regions, these jobs are held by the vast majority of workers: For example, in LAC, a staggering 86% of agricultural workers are informal. But how does this relate to the circular economy?

The Challenges of Data Collection in Informal Circular Economy Work

When work is informal, it can be challenging to collect data to understand its contribution to circularity. Many informal workers directly contribute to the circular economy — through the resale of consumer goods, the sorting of waste and the repair of damaged or non-functional items, for example — without these contributions being picked up in formal databases. Further complicating this data collection, sectors associated with the circular economy worldwide often have high rates of informality. The informal economy has, at times, acted as an antithesis to the “more, newer, cheaper” ethos of our current “take-make-waste” economy. Often stemming from necessity, activities carried out by informal workers tend to be highly efficient, maximising products’ and materials’ value, as these workers take on circular activities that are largely overlooked or undervalued. And because of the role these workers play in recycling goods and materials — for instance, by selling second-hand products — they have an unknown but potentially large effect on circularity.

Due to these factors, it’s unlikely that LAC is actually only 1% circular — but without a more accurate benchmark, it’ll be difficult for the region’s 33 nations to set accurate targets, limiting their ability to leverage the skills and expertise held in the informal labour market and roll out more formal circular economy initiatives. For that reason, data gaps associated with LAC’s informal economy perpetuate a vicious cycle: Without statistics on large parts of the working population, it’s hard to get a true picture of the circular economy in the region, or a clear sense of whether existing activities are effective — or how they can be scaled. And with a huge portion of economic activities invisible to policymakers, developing tailored strategies to bolster circular economy activities and improve working conditions in them is challenging. So while the informal economy is likely a hidden goldmine of circular practices, without recognition and support, its potential will remain untapped — and workers within it risk being undercut by policies and initiatives designed only with data on the formal economy at hand.

This is a significant missed opportunity, as circular initiatives are often labour-intensive in certain sectors. The Circularity Gap Report points to the huge potential for job creation in circular economy work in LAC: For instance, nearly 9 million new formal jobs could be created if the agrifood, built environment, mobility and waste management sectors were to go all-in on circularity. But the high prevalence of informality in these sectors means that this transition’s impact on jobs could vary wildly — without clear data, it’s tough to tell how policies driving the circular transition will affect work and workers, both formal and informal.

Supporting Informal Workers in Circular Sectors

However, despite these challenges in measuring circularity in LAC countries, one thing is clear: Shifting to a circular economy offers the region an opportunity to overhaul more than just its modes of production and consumption. If designed with social justice in mind, it can also improve workers’ livelihoods. For example, under an inclusive circular economy, those currently working as informal waste collectors, dismantlers and recyclers would be involved in social dialogues on how to transform economies for the better. Their input could help ensure that circular economy policies serve the needs of the country or city where they are being rolled out, for instance by designing social protection and labour policy to promote better working conditions in targeted sectors.

But while addressing informality (especially within circular sectors, like repair and waste management) will be critical, formalisation isn’t necessarily the end goal: Many initiatives and businesses across LAC are already providing valuable examples of how informal workers can be protected and uplifted within current systems. Cataki, for example — an app dubbed “Tinder for Brazil’s street recyclers” — matches local waste collectors (or catadores) to those with waste to discard. The average Brazilian produces around 380 kilogrammes of solid waste each year, only 3% of which is recycled — the vast majority by waste pickers. The app helps these workers decide what recyclables to pick up, based on type and location, while fostering greater social awareness of and appreciation for catadores. Policy efforts are also giving protection to informal workers in the region: For example, one Chilean law has legitimised grassroots recyclers as essential waste management actors, while also mandating that businesses must contribute to the formalisation, training and funding of these workers.

LAC countries can also look beyond their borders for inspiration: The World Economic Forum’s Global Plastic Action Partnership, for example, is using technology to measure the type and quantity of plastic that waste pickers are collecting in Ghana — bringing transparency to value chains that can benefit all stakeholders. This can uplift waste pickers by boosting their wages, since socially responsible companies will pay a premium for so-called “social plastics.” It can also benefit businesses, as research shows that consumers are over four times more likely to trust and recommend brands that have a strong purpose.

The Partnership will also support participating countries in other ways: For example, Ecuador, the first country in Latin America to join, will receive support in capacity-building through access to global knowledge and practice networks — hopefully with the added benefit of uplifting informal workers. Apps, digital platforms and partnerships like these can also be leveraged to collect and put data to work, slowly bridging gaps to clarify current benchmarks, design programmes and policies, and set targets. In the case of the Plastic Action Partnership, for instance, the new data collected will help inform public authorities’ and policymakers’ decisions on where to build new recycling plants.

Beyond Data: Other Ways to Support LAC’s Informal Circular Economy Workforce

Partnerships provide one source of data that can shine a light on the contributions informal workers make to the circular economy in LAC. But other efforts are also emerging on the data front: For instance, this year’s International Conference of Labour Statisticians adopted new standards to help countries collect better data on the informal economy. These standards will help both governments and businesses create a clearer picture of the informal economy’s contributions to the circular transition, providing a crucial piece of the puzzle in building a sustainable, resilient and socially just circular economy in LAC.

But there are other ways that informal workers can be uplifted while boosting circularity in the region, including the following actions:

- Ensuring that the contributions of the informal sector are not overlooked, and giving these workers and their activities the recognition and protection they deserve. This could include working through cooperatives that spur collaboration, providing support to formalise enterprises and building up informal workers’ bargaining power.

- Changing the narrative around informal work and workers. These workers are not actually invisible: Many formal companies rely on informally-sourced inputs and services to run their operations. Acknowledging the role these workers play in the value chains of today and tomorrow is vital.

- Bringing informal workers to the table, by giving them a say in the policymaking process and thereby ensuring that new policies do not unknowingly undercut them. These policies should also give skilled informal workers recognition and accessible opportunities for further skills development.

Through these and other actions — combined with a concerted effort to improve the quantity and quality of data available — the development community can support not only informal workers, but all stakeholders in LAC’s circular economy. If these efforts are effective, we hope that future reports will reveal greater progress in the region’s circular transition.

Ana Birliga Sutherland is a writer and editor, and Esther Goodwin Brown is the lead of the Circular Jobs Initiative at Circle Economy Foundation.

Photo courtesy of Mussi Katz.

- Categories

- Environment, WASH