Piramal eSwasthya, Demystifying the Primary Healthcare Model

Editor’s Note: This is the first of two posts on Piramal eSwasthya as part of NextBillion’s Advancing Healthcare With the BoP series.

Since its inception in 2008, Piramal Group’s (parent company Piramal Healthcare) initiative Piramal eSwasthya has worked to “democratize healthcare” through scalable and sustainable breakthrough healthcare delivery models. During the past three years, eSwasthya has experimented with several innovative approaches to delivering healthcare using telemedicine, clinical decision support systems and village-based health entrepreneurs. The model has been developed in partnership with Harvard Business School Professor Nitin Nohria and is specifically tailored to serve the grossly underserved populations in the remotest of rural areas.

Kavikrut currently heads the Piramal eSwasthya. Having spent the last five years in base of the pyramid (BoP) healthcare he has immense knowledge about the healthcare space and consumer behavior. In this period, he co-founded two healthcare delivery models (Full disclosure: Kavikrut and I, along with other team mates, together co-founded Mobile Medics ).

Sriram Gutta, NextBillion: It’s not often that we find someone with a background in finance start a career in healthcare, more so at the BoP. What led you to this field?

Kavikrut: My stint with BoP healthcare started when I co-founded Mobile Medics five years ago. This wasn’t a planned career move and happened by chance. Lack of existing solutions, a grave challenge, a good business plan, and a seed fund led me to take the plunge. I spent about 2 years at Mobile Medics where we treated 2,000 patients across 12 villages. This was a legacy model that had been tried earlier, although in a non-profit structure. A mobile van with a doctor, nurse and drugs visited a few villages each day to treat the patients. Every village was covered twice a week on a pre-defined day and time. This model was built to provide healthcare that was affordable and accessible. Although successful, doctors became the bottleneck. It was evident that to scale such a model, one needs to reduce the dependency on a doctor to deliver healthcare. In traditional models, a doctor could treat up to a 100 patients per day. We were looking for a way to increase this dramatically. While Mobile Medics was looking for funding to further experiment with other delivery models, we met the Piramal Group and saw synergies leading to the absorption of the Mobile Medics team to start Piramal eSwasthya. Their structured, well-funded and resourceful model provided a rather conducive environment to design and test more radical healthcare delivery models.

NextBillion: What’s unique about the model?

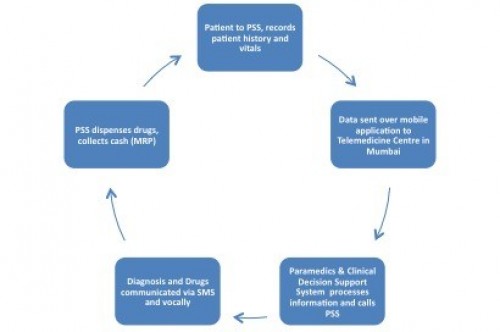

Kavikrut: Our model allows each doctor to diagnose over 400 patients per day spread across 100 villages. The doctor’s task has been decentralized and he now does what is core to his expertise, while the other steps in the treatment process have either been handed over to easy-to-train manpower or automated through sophisticated software. In a traditional set-up, the doctor diagnoses the problem, records vitals like blood pressure, pulse rate, etc. and then writes a lengthy prescription. There is also a substantial amount of time spent in talking to the patient both pre and post prescription to counsel and comfort them. We at Piramal have divided this process and have different stakeholders managing them. The key members of our delivery model are:

- Piramal Swasthya Sahayika (PSS) – A village-based health worker who acts as the communication link between the patient and the doctor. A PSS records patient history through a simple one-page form, measures vitals such as blood pressure , temperature, weight and then calls a remote paramedic based out of a call centre in a city (currently Jaipur, India). This process takes close to 5-7 minutes per patient.

- Call Centre Paramedics – The paramedics are mainly graduates who have been trained to use a Clinical Decision Support System (CDSS) to diagnose the problem. This is an algorithm-based system that is based on our belief that it is possible to automate the consultation and prescription process through clinical flowcharts, much like what a doctor would do. As prompted by the software, the paramedic asks a series of questions to the health worker, who in turn asks the same to the patient. The responses are communicated back to the paramedics

- CDSS – Based on the data made by paramedics, CDSS gives a provisional diagnosis and prescription. This software has been developed by Piramal in partnership with Tata Consultancy Services (TCS), India’s largest software service provider. CDSS can process over 70 ailments. This takes a total of 5 minutes

- Doctor – One doctor per every six to seven paramedics reads through the diagnosis given by CDSS and edits as necessary. At this point, the patient call is live and the doctor can talk to him/her, the PSS or the paramedic if needed. This is currently observed only in 10-15 percent of the cases. The doctor then approves or modifies the diagnosis and prescription provided by the CDSS. This is vocally transmitted to the patient through the health worker, and the doctor spends about 45-60 seconds in this process. A SMS is also sent to the health worker and the patient. This makes the entire process at the Call Centre to 7 minutes

As a recent health expert who visited our centre aptly put it, we have demystified the whole primary health care delivery process:

NextBillion: The CDSS seems like a path-breaking innovation. Does the system have any limitations?

Kavikrut: Yes, it does. It can only be used for primary health care and only for certain ailments. Our estimate is that 70 percent of the ailments as seen at a general physicians clinic can be diagnosed using CDSS. And these are usually the first symptoms of what later turn in to more complicated ailments requiring secondary care. So the model helps in early detection as well as treatment. There will always be a few that require a doctor’s intervention.

NextBillion: Does the use of such technology and various resources like health workers, paramedics, and doctors translate in to a higher cost for the patient?

Kavikrut: From the outset, we have tried to keep the model simple and affordable for the client. We only charge the patient a maximum retail price (MRP) on the drugs and nothing else. Since the patient never sees the doctor, we have removed the cost of consultation. This was done based on client and health worker’s feedback. Based on my experience, it is possible to make money from the drugs if one manages the supply chain well.

NextBillion: A zero cost of consultation seems extremely beneficial for this price sensitive population. Would eSwasthya be able to cover its costs in the long term?

Kavikrut: Yes. At the moment, we get an average of 1.2 patients per health worker per day across 50 villages. The model will become sustainable at a scale of 1,000 villages clocking an average of 1.75 patients/PSS/day and thus cover overheads, technology and marketing costs. Some of our better motivated health workers have consistently clocked over three patients per day and so we believe that this is achievable. We plan to scale to 1000 villages by early 2012 through eSwasthya run centres and some government Public private partnerships pilots.

NextBillion: It seems like a large segment of patients in each village are still using other health care players. Who are some of these?

Kavikrut: There are other health practitioners in or near the villages. Some of these are:

- Registered medical practitioners/quacks – Unqualified, illegal village based (sometimes travelling) practitioners that provide cheap healthcare consultation and drugs and employ questionable treatment practices such as dispensing loose unpacked drugs and using injectable steroids for treating most primary ailments. Most quacks either have the responsibility passed on over the generations or are trained nurses/compounders who pick up the trade by assisting doctors

- Government – There is a well established network of primary health centres (PHC) and sub-centres across rural India; however, these highly depend on the availability of the doctor and are not always available in the neighborhood.

- Private clinics – These are based out of nearby cities and towns and offer a doctor’s service. An average consultation fee is about Rs 50 and drugs are sold at retail price. However, the real cost incurred when seeking treatment is much higher for the client. This includes cost of transportation, opportunity cost due to the loss of wages, and other incidental expenses in the city. Making this a very expensive option.

- Quacks – These are the cheapest service providers and are inaccurate, unreliable, and unethical.

Part two of this interview will be posted Monday on NextBillion.

- Categories

- Health Care

- Tags

- rural development, scale