The Mismatch: Customers Seek Holistic Solutions, Financial Service Providers Operate in Silos

Listening to the current buzz about customers, it would be easy to conclude that the financial services for the poor sector understands little about clients’ needs for and use of financial services. In fact, we know a great deal. Yet, self-doubt persists. Why? I would argue that as we continue to peel off layers of the onion, we find that the demand for and management of financial services among the unbanked and under-banked are much more complex than we imagined.

Experts in financial services for the poor too often operate in silos, designing products to solve particular financial needs. Demand for a product type is viewed in isolation from other products on offer and relative to the other financial options available to a user. The result of this functionality paradigm is lower-than-anticipated rates of retention. The emphasis is on products for income growth or anticipated expenses. The paradigm fails to differentiate between mechanisms for coping with shocks before and after they occur, behavioral intentions and actions, as well as people’s money management practices.

Integrating these factors into the product design and delivery paradigm changes the focus beyond direct functionality of financial services to finding overarching solutions to the users’ daily financial challenges. The users’ financial services decisions are the result of a series of tradeoffs, and the value of each service is determined in relation to the immediate need.

The gap between the financial service providers’ (FSPs’) and the users’ interpretation of the market needs to be closed. In an endeavor to be more relevant, FSPs moved away from a single product line – usually the short-term working capital loan – to offering a line of marginally differentiated credit products or a variety of other financial services, such as savings and insurance. More recently, payment services have been included. Each was intended to meet a particular need. In contrast, the user blended a mix of financial services (formal and informal). Each addresses and solves a piece of the puzzle. On its own, each product fails to respond to the need for timeliness, flexibility, convenience and sufficient financing. But taken together, this “patching” works much better.

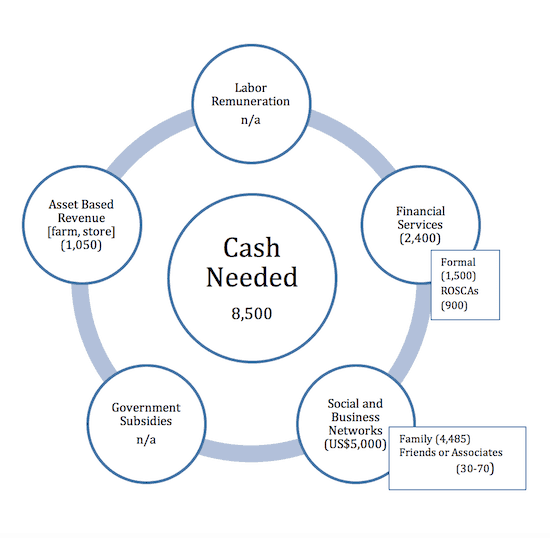

To understand how this plays out, let’s look at the story of Arthur and his wife. (Note: The story is adapted from the financial diaries work the author did in Kenya when she was president of Microfinance Opportunities.) They live in Murangi, 75 miles from Nairobi. They own a farm and a small store. The latter generates a small but regular source of income. In 2010 Arthur’s wife fell ill. Over the course of the next year the couple incurred just over U.S. $8,500 in costs, a sum well beyond their annual income but one they met without depleting their productive assets.

Note: Asset-based revenue is differentiated from labor remuneration where the latter encompasses wages, salaries or casual labour.

Over the course of his wife’s illness, Arthur’s regular cash flow from two sources – the farm and store, and the two rotating credit and savings associations (ROSCAs) to which the couple belonged – enabled them to cover nearly 23 percent of their expenses. Formal financial services – bank savings – accounted for about 18 percent. The balance came largely from social networks. Even though their cash reserves were depleted, their productive assets were not, thus ensuring a base for rebuilding their reserves. (See the chart at left.)

Access to money when it is needed, where it is needed and how it is needed are central to people’s process of money management. Access to a range of financial resources – financial services, assets, social networks and labor remuneration – and the capability to juggle the balls in space and time are vital. Much has been written on the multiple financial products people use, but little on how they are patched together for different purposes. They are rarely a static set of relationships but are ever-changing. These combinations reflect the timing of the need, the ease of access and the amount that can be tapped relative to the need. Financial diaries provide data sets that could be mined for such insights.

The challenge for digital financial service providers is to recognize these behaviors and respond accordingly, particularly to the users’ need for flexibility and timeliness.

Monique Cohen is an independent adviser and founder of Microfinance Opportunities.

Photo by frankieleon, via Flickr.

- Categories

- Uncategorized