The ‘Strange Bedfellows’ Myth: How Fintechs and Financial Institutions Can Partner for Mutual Benefit – And Greater Financial Inclusion

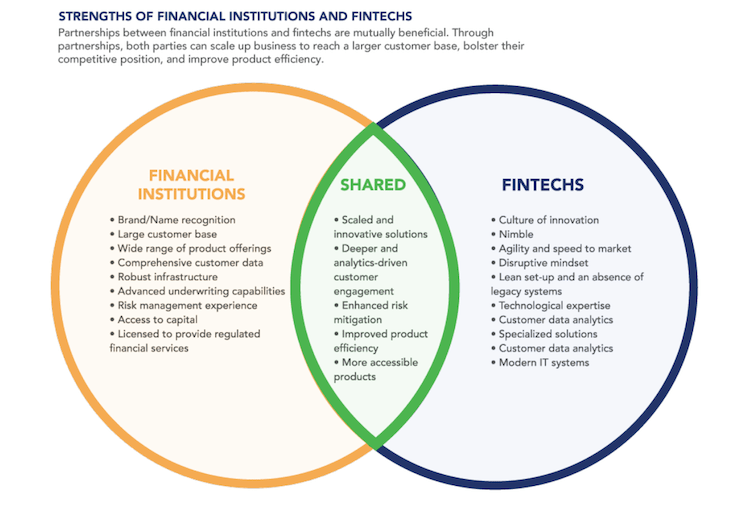

The classic narrative in tech-meets-tradition stories is essentially adversarial: efficiency gains vs jobs lost, algorithms vs people. It might be natural to expect that the rise of fintech—technology-enabled financial services—would involve conflict and clashes between the fintechs and the established players in what is, after all, a famously conservative industry. But in our report about fintech partnerships with financial institutions, the Center for Financial Inclusion and the Institute of International Finance found the opposite. Despite real differences in organizational cultures, both the fintechs and the traditional financial institutions we interviewed remained laser-focused on the huge potential upside of merging the best of their respective worlds.

As researchers, we were specifically interested in such partnerships’ potential to expand financial inclusion. The advantages to the players themselves are actually easy enough to see. Financial institutions typically have established brands and large customer bases. Fintechs, meanwhile, have technological expertise and a culture of rapid innovation. By teaming up with fintechs, financial institutions get the expertise necessary to improve product offerings, increase efficiency and lower costs in a way that might not be practical otherwise. In fact, the financial institutions we interviewed estimated that it would take them three to four times the resources to develop that same technological capacity in-house, assuming they could do it at all. For their part, the fintechs get access to expansion capital and to a massive, ready-made customer base so they can scale their technology.

In short, our research found ventures that were symbiotic rather than combative. The questions that most interest CFI and other financial inclusion advocates are: Who benefits? Will the efficiency gains and new market opportunities just boost company profits? Will they make life marginally more convenient for affluent segments that are already well served? Or could low-income consumers find themselves with quality financial services they never had before?

Four Types of Financial Inclusion Challenges

Thanks to generous support from MetLife Foundation, our report examined 14 partnerships targeted at underserved segments, especially in emerging markets. It incorporates insights from interviews with 32 people from 25 different institutions: banks, insurance companies, payment providers and fintechs. The financial inclusion challenges that these partnerships are addressing fall roughly into four key categories (although many of the challenges are interrelated and some partnerships address more than one of them):

- Gaining access to new market segments

- Creating new offerings for existing customers

- Data collection, use and management

- Deepening customer engagement and product usage

The first category holds particularly interesting lessons for stakeholders focused on the threshold issue of expanding basic access. The barriers to serving low-income customers are well known. Building physical branches in remote rural areas for a dispersed population with low-value accounts is not viable. But digital tools greatly reduce operating costs, putting affordable and accessible products within reach for hard-to-serve customers, and opening a new market for financial institutions.

Effective Partnerships to reach new markets

Our research encountered numerous partnerships between major global financial brands and fintechs aimed at serving these segments profitably.

Mastercard and Net1. Mastercard is partnering with fintech Net1 and with Grindrod Bank, a large South African commercial bank, to open bank accounts for 17 million unbanked recipients of social grant payments from the South African government. The partnership is part of a larger effort by that country’s government to digitize these payments for greater efficiency and security. Grindrod Bank provides the banking license for the operation and the bank accounts for the new customers. Mastercard provides access to point of sale (POS) and automatic teller machine (ATM) networks. Net1 provides the biometric technology and customer onboarding process. To reach low-income unbanked South Africans, Net1 developed a “cash assassination kit,” a suitcase containing tools to create a biometric identity (including a fingerprint reader, microphone, small camera and internet connectivity). About 2,500 such suitcases were set up in a variety of public locations such as the South Africa Social Security Agency offices, churches, town halls and temporary tents for recipients to visit and complete their registration. New registrants verify their identity, open a bank account and instantly receive a PIN-protected Mastercard debit card. The entire process takes about 10 minutes. Social grant payments are then disbursed into the new bank accounts at Grindrod and can be accessed through the debit cards at any location where Mastercard is accepted, including the POS and ATM networks. The partnership required Net1 and Mastercard to integrate their technologies onto a single chip that could support biometric and payment functionality. Beyond providing access to 17 million low-income social grant recipients, the partnership has created more knowledge for Mastercard, which has used the lessons learned to engage with other businesses and governments to combine payment capabilities with biometric authentication.

Société Générale and TagPay. Société Générale, Europe’s sixth largest bank by assets, put out a call in 2015 for technology partners to develop a new mobile money brand. The bank decided to work with a fintech startup for a number of reasons. While working with a mobile network operator would have offered an easier path, the bank worried that an MNO would soon seek a banking license of its own and begin operating independently, taking with it the very customer relationships Société Générale was trying to develop. The bank also wanted to set its mobile offering apart by accepting funds from any operator rather than being tied to just one MNO. A partnership with the digital banking platform TagPay – which provides digital solutions for about 20 other financial services providers, including Cofina and Trust Merchant Bank – provided the opportunity to achieve all these aims. TagPay operates the platform on which customers of Société Générale’s new mobile money brand, YUP, can transfer money. TagPay keeps a ledger of all the transactions, which are backed by a pooled account at the bank. The new YUP brand was designed to bring unbanked customer segments into the financial mainstream with fully mobile-enabled banking products. Building on YUP’s base in Ivory Coast and Senegal, Société Générale aims to reach one million new clients by 2021. To ensure that the partnership retains the necessary stability to achieve those goals, the bank has taken an 8 percent stake in TagPay.

Along with basic banking services and money transfers, low-income customers also need insurance, a financial product that has historically proven especially difficult to deliver sustainably below a certain price point. Here too, fintech partnerships hold real promise.

AXA and MicroEnsure. Like many large insurance providers, the France-based multinational AXA (ranked third in Forbes’ global ranking of insurers) built its IT and back-office systems with higher ticket value policies in mind. Each new policy can cost AXA a few dollars in processing costs, so the dollar-a-month premiums associated with low-income segments make for an unviable proposition. In 2014, AXA acquired a 10 percent stake in MicroEnsure, a UK-based social enterprise founded to expand insurance coverage among low-income people. AXA now uses MicroEnsure’s Global Products Platform to handle all data from every step of the low-income customer journey (rather than breaking up different parts of the process, as sometimes happens with higher-cost plans). The fully integrated nature of the MicroEnsure system, its all-inclusive customer relationship management support, and the simplicity of the insurance products offered all allow AXA more efficient and less costly administration. The partnership with MicroEnsure has enabled AXA to extend coverage to 10 million low-income consumers across Africa and Asia. In early 2015, it increased its ownership stake in MicroEnsure to 46 percent, a testament to its interest in playing a strategic role in this business line’s stability and growth.

New Products, New Data, More Customer Engagement

These three examples involve some of the best-known financial brands in the world using fintech partnerships as a way to reach downmarket. But they are far from the whole story. Our report found financial institution/fintech partnerships expanding rapidly to meet the other three main financial inclusion challenges identified.

Creating new offerings for existing customers

- ICICI Bank and Stellar are building a blockchain-enabled payments network.

- Stanbic Bank and DreamOval are offering a mobile payments platform for small-merchant customers in Ghana.

- Santander and PayKey are launching a peer-to-peer payments platform via messaging applications with massive user bases including Facebook Messenger and WhatsApp.

Data collection, use, and management

- MicroBank and Entrepreneurial Finance Lab are extending credit access to entrepreneurs in Spain with limited credit histories.

- Ujjivan and Artoo are reaching underserved micro, small and medium enterprises in India.

Deepening customer engagement and product usage

- BBVA Bancomer in Mexico and Bancolombia in Colombia are partnering (separately) with Juntos, utilizing its automated SMS platform to increase customer engagement.

- PNB MetLife and Imaginate are offering a virtual reality smartphone app which, in combination with a VR headset, allows users to “move” through a virtual branch office, getting answers and help with their claims, rather than standing in line in an over-crowded real one. (Eventually customers will be able to speak with virtual agents and submit claims on the platform.)

From Idea to Implementation

The growing number and scale of fintech/financial institution partnerships speak to the value proposition both sides see. That said, just because a partnership makes sense doesn’t guarantee it will be easy to execute. Fintechs tend to be risk-takers who live by the Silicon Valley ethos of “test and fail quickly.” Financial institutions tend to move much more slowly and cautiously. As Raj Chowdhury of ICICI Bank put it: “Innovation within a bank is difficult; we have a lot of regulation and require a lot of approvals.”

Moving from identifying a potential partnership opportunity to implementing an actual successful partnership depends in part on how well-organized for innovation the financial institution is, starting with whether the person sourcing the partnership has the internal clout to get the rest of the institution on board. Often, to the frustration of prospective partners, this process can be surprisingly lengthy and prone to failure. But thanks in part to the fact that there are now some real success stories, fintechs are willing to be patient because of the scale and exposure that the right partner can bring. As Carlos Lopez-Moctezuma, who leads fintech partnerships for BBVA, Spain’s second-largest bank, puts it, “Size does matter. If you are a big bank and want to work with the fintech ecosystem, it’s easier. Everybody wants to work with you.”

One encouraging and somewhat unexpected finding from our research is that the financial institution/fintech partnerships represent a slow but pervasive industry shift toward customer-centricity. Benoit Legrand, global head of fintech for ING, described banks’ historical assumption that customers would come if the banks built good products. Now, he says, “Banks need to reinvent themselves to be platforms where customers are empowered. Banks have to learn how to move and rotate around customers.”

Our research suggests that this realignment is indeed occurring – and “do-gooderism” has little to do with it. The institutions we studied saw financial inclusion as an immense business opportunity. They saw fintech partnerships as a way to make that opportunity a reality, and customer-centricity as the way to make it sustainable. If that approach amounts to “development by other means,” then these partnerships might contain useful lessons for the banking industry, both now and as the partnerships deepen and expand.

“You need more than just tech. Interoperability is about people. To get a startup’s innovations to work with your organization—and to add value to your business—you need the tech to interoperate, of course. But you also, crucially, need people.”

—Zia Zaman

Chief Innovation Officer, MetLife Asia and CEO, LumenLab

From the foreword of Lessons from the Frontline

Sonja E. Kelly is director of research at the Center for Financial Inclusion.

Graphic courtesy of CFI. Photo from Pixabay via Pexels.

- Categories

- Finance, Impact Assessment