Three Growth Strategies to Boost Sri Lanka’s Microfinance Sector

Sri Lanka has a significant low-income population segment whose financial needs are served by an estimated 14,000 financial institutions in the country, which directly or indirectly provide microcredit products. However, a majority of these financial institutions are either financial NGOs, not-for-profits or organizations that follow a local cooperative structure. For-profit formal sector microfinance institutions are few, and the market is dominated by five or six players that serve the majority of the low-income customer segment. There is limited industry research on the country’s microfinance sector, and Intellecap has attempted to bridge this gap by presenting the following market opportunities and growth strategies, based on conversations with leading practitioners, policy makers and capital providers immersed in the Sri Lankan market.

Strategies for market growth in Sri Lanka

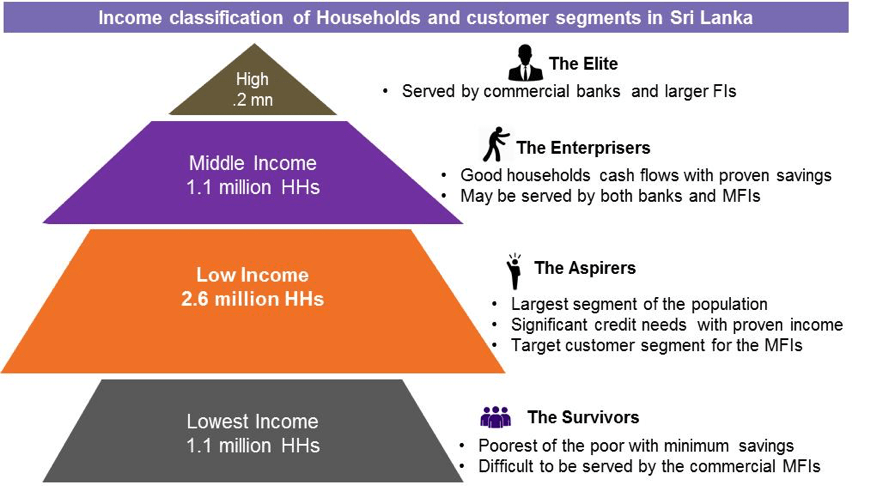

Among South Asian countries, Sri Lanka is unique in terms of population distribution by income, with a majority of its households in the low-income and middle-income segments rather than the lowest (or poorest) segment (Figure 1). As per our assessment, the country’s 2.6 million low-income households (which we’ve termed the aspirers) represent the target customer segment for MFIs in Sri Lanka. While market penetration data for the existing microfinance institutions (MFIs) and non-bank financial companies (NBFCs) in Sri Lanka is not readily available, based on Intellecap’s analysis, the total number of customers served by the five largest MFIs/NBFCs is estimated to be around 1.3 million customers. Meanwhile, the Lanka Microfinance Practitioners’ Association estimates the total number of customers served by 24 smaller MFIs in the country to be nearly 0.7 million.

Figure 1: Household income pyramid patterns in Sri Lanka

Source: Intellecap analysis based on IFC Consumption database 2013 and HIES 2012-13. Lowest refers to per capita daily income of less than US $2.97. Equivalent to monthly HH income of LKR 19,000 (2014 PPP basis). Low refers to per capita daily income between US $2.97 and $8.44. Equivalent to monthly HH income of LKR 53,000 (2014 PPP). Middle refers to per capita daily income between US $8.44 and $23. Equivalent to monthly HH income of LKR 145,000 (2014 PPP). High income refers to per capita daily income of more than US $23.

Sri Lankan MFIs/NBFCs interested in growing or consolidating their market share have to adapt different growth strategies that tap into new opportunities for both deeply penetrated segments and those segments with significant potential for expansion. Growth strategies for practitioners could be based on four specific pivots (see Figure 2), which we’ll explain in detail in the subsequent sections.

Figure 2: Proposed pivots for growth in the Sri Lankan microfinance market

Serve highly penetrated markets with innovative products

MFI players in Sri Lanka should explore strategies for market and product differentiation due to microcredit’s comparatively higher penetration levels in the low-income population. Existing players in the sector thus need to focus on deepening financial inclusion by serving unmet needs for this target customer segment; for instance, facilitating government payments such as pensions and insurance, as well as lifecycle microcredit products such as education and business loans.

MFI players in Sri Lanka should explore strategies for market and product differentiation due to microcredit’s comparatively higher penetration levels in the low-income population. Existing players in the sector thus need to focus on deepening financial inclusion by serving unmet needs for this target customer segment; for instance, facilitating government payments such as pensions and insurance, as well as lifecycle microcredit products such as education and business loans.

Innovation in product design is a good strategy to attract more customers in a penetrated market where differentiation in terms of loan size, duration or interest rates is difficult to achieve. Geographic and economic position-related products could be designed to attract more customers. MFIs could also offer value-added non-financial technical services to selected clusters of customers (see Box 1), after conducting market research and diagnostic studies to inform the development of such products. Current data on market penetration will allow practitioners to further test qualitative, macro and institutional factors in innovative product design.

Drive behavioral change for use of digital finance technology

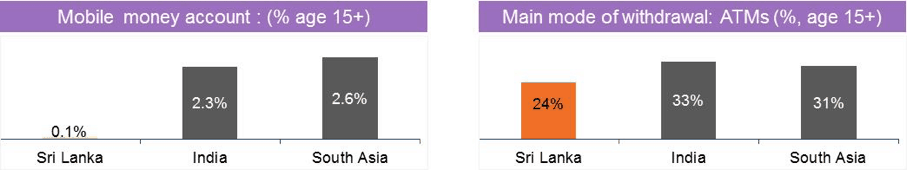

Technology and digital finance have the potential to improve access to financial services in a cost effective way. Several examples such as bKash in Bangladesh, Saldazo in Mexico and M-Pesa in Kenya have shown the power of technology for enhancing financial inclusion. In Sri Lanka, a focus on technology for enhancing financial inclusion emerged with the 2012 regulatory framework for categorizing mobile money. However, despite having higher access to mobile networks and the internet, the use of technology for financial transactions in the country remains low (Figure 3). While detailed research on the low uptake of digital finance technology is required, preliminary research indicates that it is currently linked to cultural and behavioral aspects of the low-income population. This customer segment seems to prefer cash for all financial transactions, and prefers traveling to a brick and mortar branch to withdraw money.

Figure 3: Technology usage indicators of financial services for South Asia and Sri Lanka

Source: World Bank Global FINDEX Indicators 2014 data.

Investment to encourage behavior change among low-income customers could allow MFIs and NBFCs to achieve scale and to carry out microfinance processing tasks like credit analysis, disbursements, payments and monitoring more efficiently. In Bangladesh, for instance, bKash (a mobile money system run by BRAC Bank that serves users at the BoP) has run successful campaigns to convince these users to adopt electronic money as a genuine alternative to physical cash. Through these campaigns, bKash was able to create the perception that mobile technology is easy to use, attracting 2.2 million active registered customers since its launch in 2011.

Set up self-regulatory bodies for policy advocacy, and guidelines for safe business practices

The microfinance sector in Sri Lanka is less developed in terms of its regulatory ecosystem – especially on interest rate regulations and clarity on client overindebtedness and number of loan borrowings. The market is also characterized by low barriers to entry and expansion, and at times, imperfect competition between MFIs and NBFCs. A self-regulatory body (SRO) could play an important role in policy advocacy, set up guidelines for safe business practices and customer practices, and promote market development for the country’s microfinance sector. An SRO for MFIs in Sri Lanka could work toward standards promotion, knowledge sharing and the development of transparent business environments while protecting customers. The SRO could also play a key role in attracting commercial capital to the microfinance sector, as well as advise policymakers on promoting financial inclusion initiatives in Sri Lanka. The Microfinance Institutions Network (MFIN) and Sa-Dhan in India are good examples of self-regulatory bodies and policy advocates that could be emulated.

The Way Forward

These market opportunities and growth strategies can provide a starting vantage point for relevant stakeholders to further study and closely monitor Sri Lanka’s microfinance sector. The industry is expected to reach maturity in the next few years, so market penetration growth strategies such as product differentiation and market diversification will shape the growth of successful players. It will be interesting to see the impact of the new Microfinance Bill that was passed in Parliament in May 2016 to cater to the licensing, regulation and supervision of the country’s microfinance players. Moreover, there are talks about new laws that could enable foreign capital to further boost the sector’s growth. However, deeper diagnostic study of the Sri Lankan microfinance sector is needed to identify the quantifiable market potential of various players, and to highlight key intervention areas for regulators, development financial institutions and multilateral organizations. There is also a need for a detailed study on the present market penetration levels of microcredit products, in order to design policies for customer protection on multiple lending, as well as to promote healthy competition among the various players. There is much to be analyzed, documented and discussed to set the future course for the microfinance sector in Sri Lanka, and to maximize its potential to change the lives of the country’s low-income population.

Photo: An entrepreneur in Sri Lanka. Credit: Mags’ pics for everyone via Flickr.

Vasu Kangovi is Associate Vice President, and Saurabh Sinha is Manager at Intellecap, which works in multiple impact sectors, namely financial inclusion, healthcare, agriculture and livelihoods, water and sanitation, and renewal energy across India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Indonesia and many countries in Sub-Saharan Africa.

- Categories

- Uncategorized