Convincing Customers to Buy What’s Best for Them: How Lessons from Clean Cooking Can Increase the Adoption of ‘Merit Goods’

There is a fundamental challenge facing social innovators: Despite clear benefits, “merit goods” — products or practices that improve both individual and societal welfare — often struggle to achieve widespread adoption. Even when these products and behavior changes offer solutions to pressing social and environmental challenges, traditional marketing approaches often fail to build significant consumer demand for them.

In this article, I’ll examine the clean cooking sector’s experience in selling cookstoves and fuels to emerging markets customers, and uncover effective strategies that can accelerate consumer uptake of these and other merit goods.

The Mixed Record of Traditional Demand Building and Behavior Change

For every successful merit goods campaign, dozens of others have failed to scale, or have done so inefficiently. But the successes are certainly worth celebrating. To take a couple of prominent examples: Energy Star in the United States has dramatically increased consumer adoption of energy-efficient appliances, saving Americans an estimated $35 billion in energy costs annually. Participating retailers command nearly 75% of the market for certain appliances. And Grameen Bank’s multi-channel approach to financial inclusion in Bangladesh has reached over 10 million borrowers through community meetings, financial literacy training and targeted media campaigns that transformed microfinance from an obscure concept to a common household tool.

However, many campaigns have struggled. For example, basic practices in conservation agriculture, such as crop rotation, mulching and minimal tillage, have been widely promoted by NGOs and governments due to their low cost and proven benefits. Yet adoption rates remain limited in many countries. And despite decades of public health messaging, people in the world’s largest economies continue to over-consume unhealthy foods.

The Clean Cooking Challenge: A Perfect Case Study

Perhaps no merit good better illustrates these challenges than clean cooking technologies. More than 2.1 billion people worldwide still cook with traditional, polluting fuels like kerosene, wood and charcoal (as of 2023). This practice contributes to over 3 million deaths annually — primarily among women and children in South and Southeast Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, and Central America. Indoor air pollution remains one of the leading global environmental health risks, contributing to pneumonia, stroke, heart disease and lung cancer. Traditional cooking methods also drive forest degradation, biodiversity loss and annual carbon emissions of over 1 gigaton — equivalent to the entire airline industry.

Despite technological advances in biogas, bioethanol, pellet gasifiers, liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) and electric cooking solutions — alongside numerous business model innovations — adoption rates lag far behind the requirements to meet the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 7 target of universal access to clean cooking by 2030.

The Flaws in Traditional Demand-Building Approaches

The conventional approach to accelerating clean cooking adoption combines financial incentives with information campaigns. Subsidies can significantly reduce the cost of cookstoves or even enable free distribution. Information campaigns can deliver health messaging and education through television, radio and social media, product demonstrations in communities, and pamphlets and billboards. These initiatives can require substantial investments, but they frequently yield ambiguous returns. It’s not so much that financing and information interventions are not needed — they are — but rather that they need to be applied in the right context, designed in the right way and combined with other interventions.

The sector’s traditional demand-building model rests on three hypotheses, each of which proves problematic under scrutiny.

Hypothesis 1: People will buy objectively better products

This assumes consumers rationally select products that offer objective improvements to their health or broader quality of life. However, behavioral economics reveals that people exhibit strong psychological bias toward familiar products, overvaluing their benefits relative to alternatives. Switching to a new product comes with a learning curve, requires customers to abandon familiar products and disrupts their established routines — all of which create significant “customer friction” and a tendency to maintain the status quo.

Moreover, it has become clear that people value their existing cooking methods far more than objective measures would justify. Women who have cooked with traditional methods for generations aren’t merely making economic calculations — their cooking practices may be deeply intertwined with cultural identity, family traditions and social status.

Consider bottled water in the United States: Despite blind taste tests showing no discernible difference from tap water, which is free and often healthier, bottled water remains a $255 billion global market (as of 2023).

Hypothesis 2: People lack information

Information alone rarely drives significant behavior change, especially for major purchases that alter established routines. Consumers are risk-averse and hesitant to try innovations without certainty about their benefits. Most people prefer to wait until a critical mass of others have embraced a new solution before trying it themselves.

Network science research on “complex contagion” demonstrates that while simple information may spread through weak social ties, behavior change typically requires multiple exposures from different trusted sources — what sociologists call “social proof.”

Furthermore, information campaigns can be prohibitively expensive to scale beyond individual communities. And in rural, low-income areas, clean cooking companies already incur the costs of sales agents who must travel long distances to reach target households — and who earn commissions for each new customer they recruit. Funding mass customer education campaigns can impact the already-tight margins they face in these communities.

Hypothesis 3: People lack money

While affordability constraints are real, they’re only part of the story. Millions have benefited from subsidized cookstoves they otherwise couldn’t afford. But they don’t necessarily use them consistently, often continuing to use traditional methods in parallel due to factors like unreliable or unaffordable fuel supply, incompatibility with traditional cooking techniques, and functionality issues. However, it’s not that subsidies are not needed, it’s that they need to be applied more efficiently, and combined with other measures to increase usage.

Moreover, “affordability” encompasses two distinct issues: ability to pay and willingness to pay. And it’s possible to influence willingness to pay without giving people discounts. Research shows that peer influence dramatically impacts willingness to pay. Studies from Germany, the United States and Japan show that homeowners were significantly more likely to adopt rooftop solar panels after observing neighbors doing so. In Germany, peer effects were the primary factor driving solar adoption, outweighing even financial incentives.

Reframing the Clean Cooking Approach: The User Insights Lab

After recognizing that traditional demand-building models may be useful but not sufficient for large scale transformations, the Clean Cooking Alliance developed an innovative approach to building demand through our User Insights Lab (UIL), which has been supported by the Osprey Foundation, the Government of the Netherlands, Irish Aid and Norad.

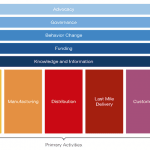

The UIL’s strategy focuses on three critical leverage points:

1. Building Value and Fit

The UIL conducts foundational research on customer needs and behaviors to help enterprises develop products and services that outperform traditional cooking methods while fitting into existing lifestyles. For example, in collaboration with University of Liverpool researchers, the UIL deployed a diagnostic tool that helps enterprises understand why consumers continue using traditional fuels even after acquiring clean cookstoves. One revelatory insight was that a high share of LPG cookstove users in Kenya switch back to traditional technologies when they cook food that needs to boil for a long time, such as beans and githeri (a beans and maize dish). They don’t see LPG as being fit for that purpose, due to the expense — and they also found that LPG stoves tended to burn flatbreads such as chapatis.

The UIL also works with ethnographic researchers who spend extensive time in consumers’ homes, interviewing them and observing their cooking practices. This research is helping electric pressure cooker (EPC) manufacturers understand some of the factors driving and hindering EPC usage. For example, it revealed that inhabitants of urban areas with small living quarters often struggle to find storage space for their EPCs, sometimes forcing them to keep the appliance outside the kitchen, creating a barrier to regular use. Additionally, many people find the EPCs difficult to operate and don’t find the instruction manual to be very helpful.

2. Reducing Conversion Costs

The UIL is also looking at multiple ways to drive down the total cost of converting customers to clean cooking — whether that involves companies paying for advertisements and sales agents, governments paying for subsidy programs, or advocates paying for awareness campaigns. As with many merit goods, there are significant opportunities for boosting customers’ willingness to pay for clean cooking, beyond simply increasing the size of the subsidy. For instance, the UIL’s research shows that smaller subsidies on expensive products are more effective than large subsidies on cheaper products. This kind of data can inform national and international subsidy programs.

One initiative with the Clean Cooking Association of Kenya examined whether energy efficiency labels would increase consumer willingness to pay for improved cookstoves. It found that while putting an energy efficiency rating label on a charcoal stove increased the price people were willing to pay for that cookstove (particularly if the rating was high), that increase was not nearly enough to make up for the more expensive price tag of an efficient cookstove.

3. Reshaping Industry Culture

The UIL also works to transform the clean cooking sector’s culture from technology-centric to customer-centric. To achieve this, it conducted surveys of people who use clean cooking technologies, to better understand their experience.

For many enterprises, this data proved revelatory. For example, 29% of customers reported that they experienced challenges with their clean cooking technologies, and a full 74% of them said the challenge had not been resolved. With this data in hand, some clean cooking companies have taken significant steps to improve their customers’ experience, resulting in stronger customer advocacy for their brands.

Broader Lessons for Merit Goods Beyond Clean Cooking

The Clean Cooking Alliance’s journey from traditional demand-building approaches to a more nuanced form of thinking offers valuable lessons for organizations working with any type of merit goods. And many times, these lessons involve the need to question our assumptions around what drives change — and to sketch out the underlying logic, and identify and validate hypotheses, when our demand-building initiatives struggle.

For example, traditional awareness campaigns based on the health benefits of clean cooking assume people are willing to pay more for products that will provide them with benefits that won’t materialize until far in the future. Merit goods companies and their supporters should watch for red flags, like assumptions around perfect rationality among customers, market competition or information access. They should frame their objectives around the desired system changes (e.g., how might we get people to perceive the value of clean cooking solutions as worth their cost?) rather than around assumptions about what the specific solutions should be (e.g., how might we decrease the cost of clean cooking solutions?). And they should remember that interventions that over-simplify customer decisions rarely succeed. Ultimately, the high level of effort and costs required to convert customers to clean cooking are not only symptoms of the lack of ability to pay, but also of a low willingness to pay, which stems from inadequate product-market fit and insufficient social proof.

By questioning assumptions around behavior change, organizations can develop more effective strategies for scaling up the adoption of merit goods and accelerate progress toward critical social and environmental goals. The clean cooking sector has learned this lesson through hard experience: Other merit goods providers can benefit from these learnings as well.

Jean-Louis Racine is Chief Program Officer at the Clean Cooking Alliance.

Photo credit: Ranyee Chiang for the Clean Cooking Alliance

- Categories

- Energy