‘The Marketmakers’ – How Rural Bangladesh Became a Model for Solar Enterprise

Rural business is tough. While India’s rooftop solar installations continue unabated in cities and towns, over 300 million people lack adequate access to electricity in its rural and remote villages. And still today, up to 70 percent of village households in developing countries throughout Asia and Africa have little access to energy services.

This was, in fact, rural reality for nearly 100 million people at the turn of the 21st century in Bangladesh when a national program for solar home systems changed everything. Within a decade, Bangladesh was on its way to becoming the world’s fastest growing off-grid solar market. Local suppliers, trained technicians and nearly 50 rural companies served every district of the country.

But how did rural Bangladesh harness and conquer the off-grid energy market? Bangladesh is a delta with more navigable rivers than roads. It’s plagued with monsoon rains, seasonal floods and cyclones, which can destroy entire rice harvests, shrimp farms and small farmers’ livelihoods. Its low-income rural population was thus highly reluctant to spend its limited resources on an exotic solar technology few knew anything about. And now, in only one decade, 15 million villagers are enjoying the benefits of solar home systems? This is hard to believe.

Further questions arise: Was this perhaps the work of some high-tech company? Even more baffling: what company would risk starting a business in an undeveloped rural market? And why was this solar technology chosen to develop the market?

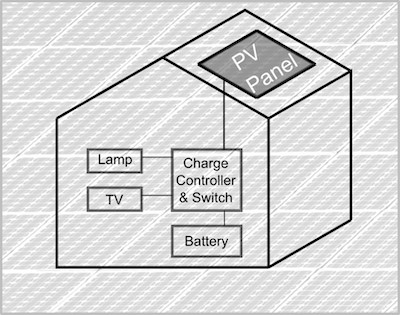

A Solar Home System (SHS)—a PV-panel on the roof, a battery and a controller in the house—generates and stores electricity and feeds lamps, television and mobile phones.

Solar home systems have few components, are quick to install, easy to maintain and easy for technicians and village customers to operate. They can be transported to the remotest villages and powered the appliances villagers needed most: lights, TVs, mobile phone chargers, fans and hand tools. Shop owners used TV to attract more customers and light to work after dusk to increase their income.

If developing a solar market had merely been a matter of marketing a leading technology—as some high-tech companies actually believe—solar business for rural households would have been an immediate success. Unfortunately, creating a market for an unfamiliar technology in Bangladesh’s hinterland isn’t quite that simple.

This market did not emerge by chance. Here, new ideas were at work with both the leadership and the resources to put them into practice: the World Bank as investor; IDCOL, Bangladesh’s financial intermediary, as market manager; and rural entrepreneurs as service providers. Together they developed a rural market from scratch—step by step.

No doubt, the solar home system market leveraged certain characteristics unique to Bangladesh that would be difficult to replicate in other countries. Nevertheless, I am convinced its success is not entirely determined by a certain country and product. Rather, its success stems from a market-oriented approach carried out by rural entrepreneurs and the leadership and resources to see it through. This approach could be adapted to work elsewhere. But only if its inner mechanics are well understood. My book: “The Marketmakers—Solar for the Hinterland of Bangladesh,” is narrated from the different perspectives of the people who made this market happen. Below are a few adapted excerpts.

The Power of Prudent Market Design

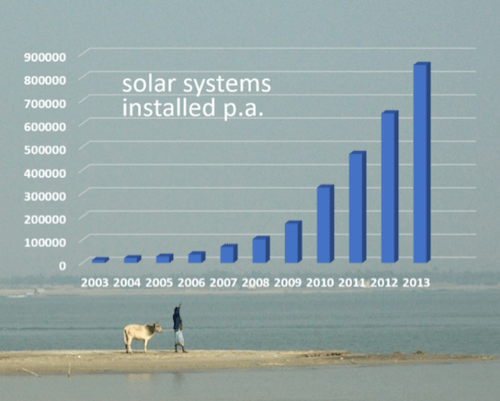

As market manager, IDCOL conceived this market as a complex machinery of rural entrepreneurs, multilateral donors, technical suppliers, financial models and rural distribution networks that make things happen large-scale. And this succeeded. In little more than a decade, rural entrepreneurs were installing 65,000 solar home systems a month by 2013.

But this market would not have taken off all by itself, nor would its complex machinery have functioned smoothly without active leadership. IDCOL’s founding CEO M. Fouzul Kabir Khan excelled in designing this market model. IDCOL defined the rules of cooperation early on for this system to function—a contractual agreement which bound all entrepreneurs to abide by important rules. It installed a Technical Standards Committee to maintain quality assurance complete with regional monitoring offices and a call center for customer complaints.

The solar market in rural Bangladesh—a decade of development

Unique in IDCOL’s approach, however, is how it communicated with the field practitioners. It not only understood the crucial importance of leveraging the expertise of rural entrepreneurs to develop the solar market. It also knew that as a financial institution for large infrastructure projects, it would have a great deal to learn about the nature of decentralized business if this project was to succeed. IDCOL’s CEO deemed this expertise so vital to the success of the program that he established the Operations Committee to convene monthly meetings with rural entrepreneurs and IDCOL’s management. Khan explains why he chaired these meetings himself:

“You must first understand that we are talking about rural business, which financial institutions have traditionally failed to recognize as very different from business as usual. A traditional financial institution works only at arm’s length with its partner organizations. But we work closely with our rural entrepreneurs and customers to see what the problems are. We want to know how entrepreneurs can improve their service. This was the reason for creating the Operations Committee. It acts as a catalyst. It gives rural practitioners a chance to meet face-to-face with IDCOL’s CEO, to vent their feelings, to complain, and most importantly, to learn from each other. And make no mistake: if I don’t make the entrepreneurs’ life comfortable, they will make my life a nightmare.”

IDCOL installed the institutions needed to achieve technical and organizational quality in the market and actively contributed to their success. But what if the market manager had steered a different course―if it had opted for a conventional development project that distributes subsidized solar systems to the rural population or even donates them for free as a handout? This approach—although often favored by governments — fails to create a market. In fact, it can be counterproductive, as examples in “The Marketmakers” show.

Instead, IDCOL strived to grow a rural market by fostering entrepreneurship, competition and innovation. A sophisticated financial model was designed with financial incentives and technical support to attract rural companies and create competition. Subsidies were tied to the performance of the entrepreneurs and declined as the market matured.

No, we don’t want to spoil the customers with subsidies,” stressed a senior manager. “Rather, we give financial and technical support to the rural entrepreneurs to remove the bottlenecks, so they have incentives to drive the market.

In less than a decade the demand for solar systems continued to soar in spite of the sharp decline in subsidies. What accelerated market growth in the long run was IDCOL’s innovative financing model. Rural companies were granted soft loans at a reduced interest rate of 6 to 8 percent with a 6 to 8 year loan tenor. This gave them time to grow the market—but only if they managed excellent service, proper installations of the systems and thus achieved high recovery rates. Everyone had a stake in growing the solar market and shared part of the risk, including the World Bank. Millions of solar systems could only be installed because of its investment of half a billion U.S. dollars.

But what about the important role of technical assistance? When local entrepreneurs began operations, they spent most of their time, money and effort not on solar technology — but on making villagers aware of its benefits and training its field staff. At the start of the solar program, marketing and training consumed as much as 70 percent of all branch office activities. And later, companies could only expand operations as fast as they could train their field staff. A field manager of a fast growing company complained:

We had installed a total of 130,000 solar systems and were under pressure to scale up branch operations. But how fast can you scale up if you don’t have skilled staff? We stepped up recruitment and our branch managers did on-the-job training―and still 36 percent of the new recruits dropped out. Rural service is tough.

IDCOL’s generous support for technical assistance thus relieved rural companies of a major financial burden, while giving new and often smaller entrepreneurs the benefit of a better start in the solar market. A good example is a microfinance organization (MFI) working with the tribal people in the Chittagong Hill Tracts. Here training new staff is unbelievably tough. Villages are spread across great distances and it can take you more than a day to reach a single customer. But with IDCOL’s tailor-made technical and financial support it could bring solar power to the tribal people.

Many more examples illustrate how a partnership between an investor, market manager and rural entrepreneurs developed the world’s largest off-grid market for solar home systems. But nothing in the business world stands still: Customer behavior and preferences change, technology marches on, globalization takes its toll and new competitors appear.

How the market-makers in Bangladesh adapted to market change – or didn’t – is an important part of my book’s narrative. Their profound contribution, however, is not only that they created a market in the hinterland where business is tough. They demonstrated to the world how this market created thousands of jobs and supported local manufacturing and innovation. Most important, they laid the foundation for solar business to continue after the solar home system project reached closure – in many new and unexpected ways.

Nancy Wimmer is the author of the 2019 book, “The Marketmakers—Solar for the Hinterland of Bangladesh,” as well as “Green Energy for a Billion Poor—How Grameen Shakti Created a Winning Model for Social Business.”

Photo: a “solar village” in Bangladesh (photo courtesy of the author).

- Categories

- Energy