Water, Water Everywhere: The Importance of Context, Partnerships

Editor’s note: This week we feature a four-part series analyzing community-scale water solutions using the 5 P’s framework: Population, Problem, Product, Process, and Partnerships. The series was contributed by researchers from the Rural Market Insight team at the Centre for Development Finance (CDF), who recently spent a month in Rajasthan discovering Base of the Pyramid consumer preferences for treated water.

We encourage you to engage in the discussion by adding your comments and questions to the posts. You can also participate in Ask Acumen, which this week offers the opportunity to learn more about Acumen Fund’s work with social enterprises that address water-related challenges.

“The soul of India lives in its villages.”

Without a doubt, the findings on BoP consumer preference from our month-long pilot study with Sarjaval in northeastern Rajasthan often evoked Mahatama Gandhi’s words. Perhaps the diversity within communities, regions and even states gives India its character, its soul.

The three areas we visited, situated within two hours of one another by road, could have been scattered across India as the culture, economy, drinking water availability and consumer behaviors varied considerably. While some consumers in Jhunjhunu district were wealthy and educated enough to invest in home water filtration systems, other families living near the southwestern border of Haryana vowed never to pay for water. Villagers near Fatehpur were dependent on government schemes, while families near Chirawa have relied on private companies for years. Some villages practiced Purdah, while elsewhere both spouses worked outside the home. Diversity, it seems, defines India’s culture and its drinking water practices.

Today, India’s soul resides with almost three-quarters of its 1 billion plus population spread across in 6,38,000 villages (2001 Census). So, how do social enterprises reach the heart of the BoP market when villages are so scattered, and, moreover, distinct?

(An in-home filter in BanGothodi village)

First, developing a deep understanding of the local context is essential for operations. This was well evidenced by the fact that Sarvajal’s plants operated slightly differently in each of the areas we visited. But, we realized that there were still 637,997 villages we left discovered. While our insights are transferable, unique needs in every village should be understood for water services to solidify partnerships and grow the business.Sarvajal’s franchise model, which allows for slight changes according to each village’s unique context, has led to 125 franchises throughout Gujarat and Rajasthan. For these businesses to flourish, not only must the community be understood, but the franchisee (or entrepreneur) must play a respected role in the village. Potential BoP consumers, especially in illiterate communities, sought advice from family and neighbors more often than newspapers, private TV channels and other forms of mass communication.

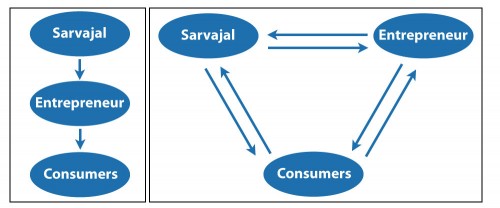

Word-of-mouth marketing should be captured, not feared. The triad of stakeholders, including the consumer, the entrepreneur and the parent company, must actively engage in communication, data collection and implementation and in participating with plant operations. Participation, we found, increased trust among consumers and strengthens the brand.

(A traditional top-down approach, left, will not work for social ventures working with the BoP. Instead, two-way relationships spur active participation from all stakeholders. Sarvajal works with a local entrepreneur/franchisee to run water filtration plants within communities).

(A traditional top-down approach, left, will not work for social ventures working with the BoP. Instead, two-way relationships spur active participation from all stakeholders. Sarvajal works with a local entrepreneur/franchisee to run water filtration plants within communities).

The parent company (in this case, Sarvajal) must forge two-way relationships with the entrepreneur and the consumer to ensure that operations, marketing and distribution work together and gather feedback and insights for continual product improvement. While clean drinking water is fundamental to good health and survival, purchasing it is still a subjective choice. Current consumers may have limited options, but eventually, brand loyalty and customer satisfaction will be top concerns for filtration companies in India’s water sector.

Education, awareness and communication strategies are critical tools for influencing consumer perception and increasing the BoP consumer base. Tailoring strategies for the context requires rigorous qualitative and quantitative market research in villages to get to know the BoP consumer before the product is launched. In one village, a mural on people’s daily commute may be the best advertising, whereas in a village just up the road, door-to-door direct marketing might be the only way to reach remote areas. To develop effective tactics, first understand the context and region, and then focus on building solid partnerships with all stakeholders involved. Understanding context and building partnerships is important for scaling up any product or service in the BoP market in rural and peri-urban areas.

In this case, success depends on using the Social Entrepreneur’s 5 P’s – population, problem, product, process, and partnerships – so that more people understand the benefits, more people drink clean water and, thus, more people are able to live healthier lives. Hopefully, one day the soul of India will be rejuvenated with clean drinking water across all of its 638,000 villages. Until then, for Sarvajal on to franchisee 126…

(Above: A group of National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) workers in the village of BanGothodi take time to discuss the pros and cons of filtered drinking water with us. In this village, even the Sarpanch practiced Purdah with her family elders).

Special thanks to David Fuente, Geetanjali Shahi, Bree Bacon Woodbridge, and the team at Sarvajal for their help throughout this series.

- Categories

- Uncategorized

- Tags

- partnerships