From One Crisis to Another: Using Data from COVID to Meet the Looming Challenge of Food Insecurity

Due to a tragic combination of events, countries around the world are facing a widespread and serious food shortage. In 2020, the economic impacts of COVID and the worsening effects of climate change presented unprecedented challenges to food producers and supply chains globally. Then, just as many people’s lives were stabilizing, the war in Ukraine accelerated inflation and upended the supply and distribution of agricultural commodities. For instance, almost all low- and middle-income countries saw food inflation levels above 5% from May to August of this year, with many experiencing double digit inflation in this period.

In light of these disruptions, the World Food Programme predicts that the number of severely hungry people will swell to 323 million over the course of 2022. Looking forward, climate change will perpetuate many of these challenges in the coming years, causing lower agricultural yields and malnutrition. And sadly, those whose survival is already a day-to-day struggle will suffer the most, including many FINCA customers.

According to data we collected in 2020 and 2021, nearly four out of five FINCA customers experienced worsening food security because of COVID. People facing food insecurity need different types of support, depending on their circumstances. For those in extreme poverty, food and cash aid are needed to prevent starvation. At the same time, financial inclusion organizations like FINCA can adapt our support to address the evolving needs of our customers, who sustain their families mostly through self-employment and small-scale farming. Low-income people are already skilled at getting by on limited resources. With our help – in the form of responsible credit, savings and financial education – they may be able to stave off the worst effects of the worsening food crisis. Further expanding our investments in local agriculture, food processing and distribution will also help.

To help our low-income customers navigate this issue, we’ll need to employ the same flexibility we adopted during COVID-19 in the coming months and years. Such flexibility could entail the development of more customized digital services, the adaptation of customer care services, and the provision of flexible access to credit, savings and financial education. At the same time, both financial inclusion organizations and other entities in the public, private and development sectors must dedicate more resources to strengthening local food supplies and building the resilience of those whose wellbeing is most in peril. Below, we’ll discuss how the food crisis is affecting the communities we serve and explore some of the ways FINCA is working to lessen these impacts, using data we initially gathered to inform our COVID-19 response.

REDUCED FOOD QUALITY, SKIPPED MEALS AND SEVERE HUNGER

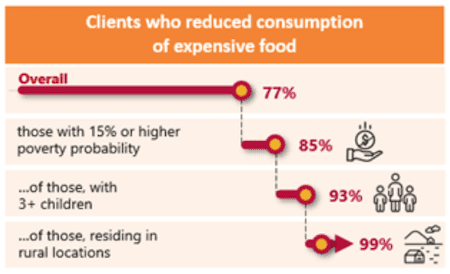

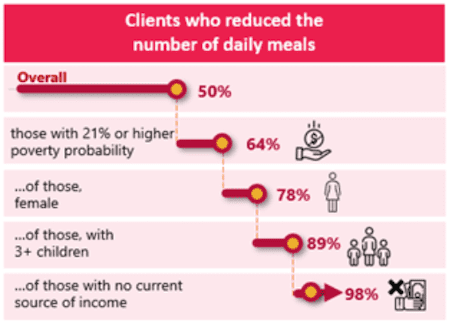

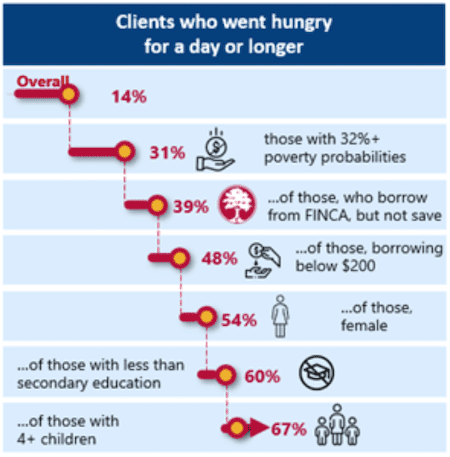

Survey data that we collected with support from the Social Performance Task Force showed that 77% of our customers reported deteriorating food security at different levels of severity in 2021-22, ranging from reduced consumption to going a day or more with nothing to eat. Our analysis of the consolidated data set, representing 11,000 respondents from 13 countries in Latin America, Africa and the Middle East/South Asia, delivers a clear picture of the risk factors that predict deteriorating food consumption. As illustrated in the three graphics below, our data describe who was affected and how, by estimating the relative contribution of three risk levels to food insecurity, along with their cumulative impact. (Data are from FINCA’s Mission Monitor Survey.)

Reduced Food Quality: In terms of the first risk level, reduced food quality, we found that eliminating “expensive” foods was extremely widespread among our customers. This is troubling, because consuming lower quantities of high-cost items like meat and dairy can have severe health consequences, particularly for children and pregnant or nursing mothers. Income is the obvious driver of this risk: We found that eliminating the top earners in our sample raises the likelihood of degraded food quality from 77% to 85%. When considering household size (including only households with three or more children in the sample) and the disadvantages of living in a rural area, we found 99% probability that the household downgraded their food consumption. This is a vivid example of the particular vulnerability of rural households, who suffer the most from malnutrition and whose livelihoods are directly impacted by supply chain disruptions and climate change.

Skipping Daily Meals: This experience isn’t always a sign of serious food insecurity: Under normal circumstances, skipping the occasional meal is not particularly worrisome. But when it is forced upon a household due to the inability to procure food, it raises a major concern. Our model shows that raising the poverty threshold increases the likelihood of regularly skipping meals from 50% to 64%. Gender is another factor that affects this risk, especially when compounded with a larger family size of at least three children, as women and girls globally account for 60% of the chronically food insecure. This is consistent with other findings that women and girls tend to eat last and least within their households in countries facing conflict, famine and hunger.

Severe Hunger: We found this level of food insecurity in about 14% of our clients, who reported going hungry for a full day or longer. And we identified a distinctive set of factors that increase the probability of severe hunger from 14% to 67%: For instance, just eliminating those with a low probability of poverty (30% or less) doubles the incidence of severe hunger to 31%. So this issue lurks beneath the surface, even if it seems less common at first glance. Other factors that increase the likelihood of severe hunger include lack of savings, borrowing small amounts (<$200) and being a woman with less than secondary education. By adding a larger burden of childcare (at least four children) to these other conditions, the risk that a female customer with small loans experienced severe hunger due to COVID-19 rises to 67%. This data makes a compelling point on its own, but hearing directly from our female customers about going to bed on an empty stomach makes it impossible to ignore.

COUNTRIES AT RISK OF A FOOD CRISIS

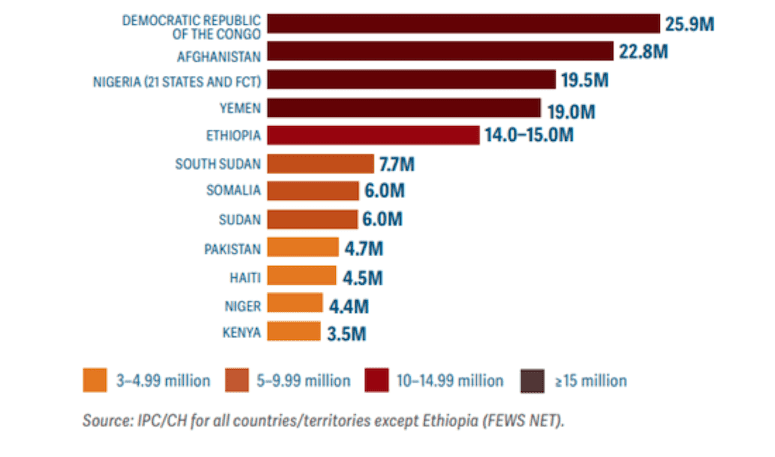

As food insecurity rises to the forefront of global challenges, world leaders are calling for urgent action, warning that for each percentage point increase in food prices, 10 million people are forced into extreme poverty. A 2022 World Food Programme Report describes the severity and magnitude of the food crisis, which will impact some countries more than others. In Haiti, to take one example, severe hunger could affect nearly half of the country’s population.

Countries with over 3 million people forecast to be in food crisis or worse in 2022

In response to this escalating crisis, FINCA is strengthening our focus on financial health and resilience across many areas, especially product development, service delivery and research. We aim to help customers avoid hunger by enabling them to build wealth and manage financial resources. We are also devoting more resources to lending to sectors directly related to food production, such as agriculture, food processing and distribution, while investing in technologies that help us serve people in remote areas.

The COVID pandemic was a universal event, in that it affected everyone at the same time in similar ways. Food insecurity will be a more localized and seasonal problem, happening at different times and affecting certain households more than others. Financial inclusion organizations like ours will also be impacted, as the crisis will influence the demand for savings and credit, and impact clients’ ability to service their debts. But while the scale of the challenge is smaller than COVID, it will nevertheless require an urgent and comprehensive response that involves organizations, businesses and other entities across sectors. And as was the case with COVID, data will be a key part of this response, since only by considering the risk factors that are driving food insecurity and hunger can we predict – and lessen – their worst effects.

Scott Graham is Vice President for Research and Data Science at FINCA International; Andree Simon is president and CEO of FINCA Impact Finance; and Anahit Tevosyan is Director of Research at FINCA International.

Photo (and homepage photo) courtesy of EU/ECHO/Anouk Delafortrie.

- Categories

- Agriculture, Coronavirus, Environment, Finance